Editor's note: This is the first of a three-part series assessing the rebounding job market for Duke seniors. Today’s article focuses on the new opportunities and career paths available to graduates. Tuesday, The Chronicle will analyze why the finance industry attracts so many recent graduates. Wednesday, The Chronicle will look at the growing trend of underutilized degrees and how Duke students are affected.

By Fall 2007, then-senior Molly McGarrett considered herself as good as employed. After completing an internship for a large foreign bank over the summer in New York City, she snagged an interview at another bank before classes began. By November, she had an offer.

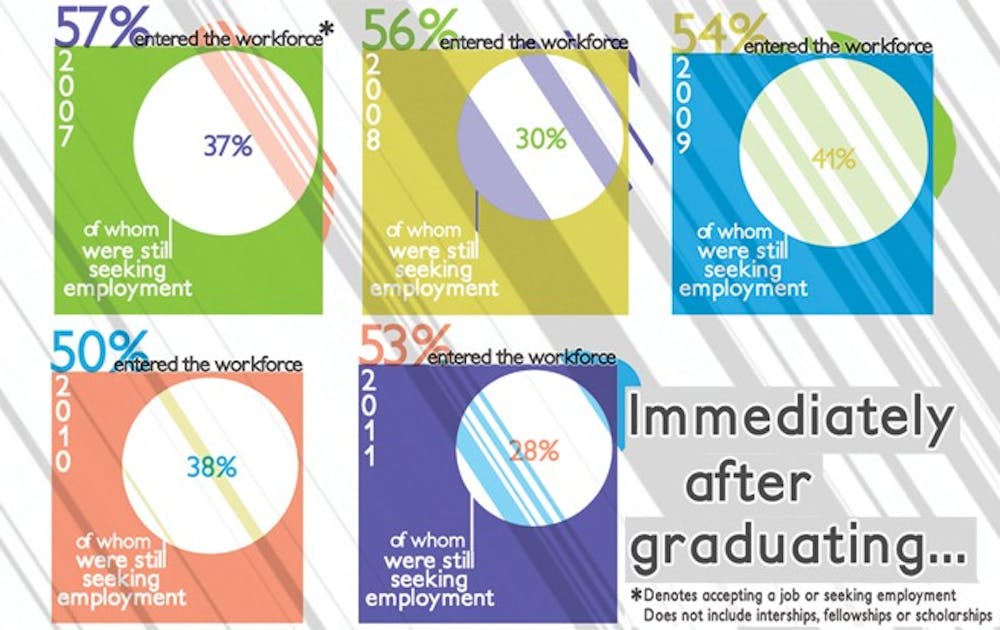

But as the economy worsened, so did the job outlook for Duke students. McGarrett’s offer was rescinded in April 2008, prompting her to restart her job search. Approximately 17 percent of Duke seniors in 2008 were still searching for work at graduation, according to the 2008 Career Center senior exit survey. The next year, the market worsened. Nearly 22 percent of the Class of 2009 considered themselves to be unemployed at the end of senior year.

The prospects have improved since then, and current seniors—who came to Duke at the height of the financial crisis, just months after McGarrett and her classmates entered the labor market—are presented with increased opportunities. Employers surveyed expect to increase hiring of new graduates by 10.2 percent this year, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, a nonprofit professional organization.

But Duke seniors still face a challenging marketplace. Today’s job market is characterized by mobility and change but also fierce competition.

“Is it a secure world? No,” said William Wright-Swadel, Fannie Mitchell executive director of the Duke Career Center.

Students are seeing a shift in the type of job opportunities available, with more short-term commitments and leadership development programs, Wright-Swadel said. Half of the companies that currently recruit on campus began coming to Duke in the past four years, he added.

Since February 2010, all private-sector industries, except information, have added jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Jobs in professional and business services added the most jobs at more than 1.2 million, outpacing manufacturing, which added nearly half a million.

“Half of the jobs you’re going to do in your lifetime have not been invented yet,” Wright-Swadel said. “That does create for our students a very volatile marketplace.”

New expectations

Shorter commitments are becoming the norm for both students and employers.

Duke graduates who pursue a job in finance, the most popular industry for Duke students, or at Teach for America, the top recruiter of students at the University, typically make two or three-year commitments. Because approximately 90 percent of Duke students plan to earn an advanced degree, most Duke students are not looking for a long-term engagement straight out of college, Wright-Swadel said.

“The reality is there are many people who are doing four years in four different companies,” Wright Swadel said, noting that Duke graduates will likely switch firms many times in the course of their careers.

John Caccavale, who was a banker for 30 years at J.P. Morgan and Barclays Capital before returning to Duke to work with students interested in finance, noted that it used to be common for people to work at the same firm for their entire careers.

“That doesn’t happen anymore,” said Caccavale, Trinity ’81 and executive director of the Duke University Financial Economics Center, which fosters connections between the corporate world and the University.

But less interest in long-term engagements on the students’ end comes at a price. New workers are less likely to see the same type of security that older generations experienced in the labor market.

“The kind of parental relationships [that] companies used to have where they hired you and then they developed you, that’s less true today than it’s ever been,” Wright-Swadel said.

Phil Gardner, director of the Collegiate Employment Research Institute at Michigan State University, added that companies are no longer as loyal to their workers as they tended to be 30 years ago.

“Anyone under the age of 35 better get used to this,” Gardner said. “They’re not going to get loyalty back.”

Reinventing the career

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Kellan Dickens, Pratt ’07, graduated from Duke with three job offers. After a three-year stint in consulting, Dickens enrolled in business school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and will graduate this year. Now, he is about to embark on a two-year renewable energy rotational program at General Electric Co., his “dream job.” Eventually, he would like to start his own company and work in a third world country.

“If the opportunity [to start my own company] were there, I would take it,” Dickens said. “One thing Duke teaches you is the value of taking risks and the value of doing something crazy once in a while. It’s valuable to go out and leave an imprint on this planet.”

Although Dickens has changed paths three times in the past five years, Wright-Swadel called his postgraduation ventures highly typical.

Individual companies may suffer initially from the constant workforce turnover, but in the long run, this turnover will benefit the economy because employees will be able to find their best-fit job, Gardner said.

The market will look different five and 10 years from now, as new jobs are created and old jobs become obsolete, he added.

“You’re going to reinvent all these jobs to fill that gap and keep producing,” Gardner said. “That’s the silver lining. But right now we’re just worried about jobs lost.”