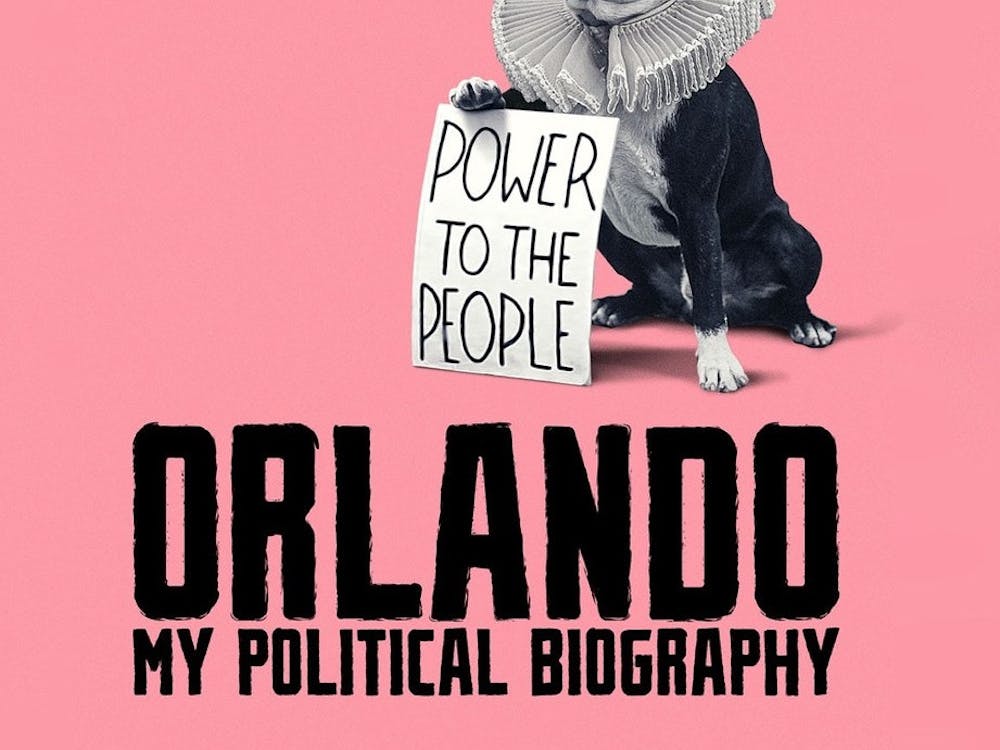

On Friday, Jan. 31, “Orlando: My Political Biography” was screened at the Ruby’s Film Theater as part of Duke’s annual French Film Festival. The film premiered at the 73rd Berlin International Film Festival, where it took home the Teddy Award for Best Documentary Film.

The film is inspired by Virginia Woolf’s biographical novel “Orlando,” which documents the life story (which spans over 300 years) of the main character Orlando, who transforms from a man to a woman and experiences significant historical and sociopolitical changes. Paul B. Preciado, the director of “Orlando: My Political Biography,” casted a diverse group of transgender and non-binary identifying individuals to play the role of Orlando. The film extends the original novel to document the many versions of Orlando under modern and contemporary contexts, exploring the ongoing struggles of transgender individuals today.

The event was opened by Dr. Eric Disbro, Assistant Professor of Romance Studies. Quoting the film, Disbro introduced Woolf’s biography, “Orlando,” and Preciado’s film applying Woolf’s study of sex and gender to the modern era — asking the audience to ponder how those same topics apply to the modern United States.

Delving into themes of embodiment and monstrosity, Disbro pointed out that the film’s presentation of rage, which, to me, is a rage that questions the unjust, existing institutions and the thresholds that prevent the entrance of trangender and nonbinary individuals. Time has elapsed and now there are a myriad of messes — modern psychiatry, colonialism, racism, etc — unprecedented in Woolf’s era. Literary economy is inextricable from trans experience, as Disbro stated, and the question is, how would (auto)biography “not be a fraud?”

“Orlando: My Political Biography” opens with a question: “what is really your sex?” The question, typewritten in red letters on a black screen, is followed by real-life scenarios of transgender and nonbinary individuals being asked to clarify their “real” sexual and gender identity. In doing so, the documentary interrogates the contemporary notion of gender binarism and fixedness.

Multiple portrayals of the titular Orlando come into place — the film employs a polyphonic approach, where multiple individuals across different time frames contribute a unique perspective from a specific period. Plots unfold as each individual introduces their name and their role (Orlando) in the film. The very first few scenes are introduced by Orlando – played by Oscar (Rosza) S Miller — reading a letter they wrote to Virginia Woolf. Afterwards, Oscar wandered in a stretch of lush forests, acting and revising Woolf’s description of Orlando, who “naturally loved solitary places, vast views and to feel himself for ever and ever and ever alone.” As Oscar reads on, other actors join – as voiceovers – reading the letter along with Oscar, like a polyphony where different timbres of voices collide to create a complex line of melody, all celebrating their representations in the biography Orlando.

While the actors echo Woolf’s portrayal of Orlando written in 1928, they challenge its historical limitations. Preciado presented voices of dissonance as well: Orlando’s transformation in gender identity means not only to become an Other but Others — it is usually a group not an individual who carries stigmas not an individual, and the modern Orlandos still face structural inequality. Though Woolf successfully portrayed the confrontation between transgender individuals and imperial power, she fails to mention transgender individuals’ confrontation with modern psychiatry after the 19th Century. “Life is not a biography,” as one Orlando posed, instead, life contains the metamorphosis of self and the process of giving in to let oneself be transformed by time.

In a scene with Orlando (Liz Christin) and a psychiatrist Dr. Queen (Fréderic Pierrot) — a scene re-enacting the book’s encounter between Orlando and Queen Elizabeth — the two characters debate gender binarism under the context of conversion therapy. In this scene, Dr. Queen continuously questions Orlando’s gender identity, following a binary logic — if Orlando states that Orlando’s is not a man, Orlando must be a woman. The Doctor refuses to acknowledge Orlando’s identity, believing that gender is determined by genitals. It is worth noticing that Orlando responds by labeling binarism as a modernist construct, which seems counterintuitive as people generally relate modernism with a break with traditions and more self-explorations. If so, what would be literary modernism’s role in shaping or reinforcing the gender binary? Instead of seeing modernism as a radical break from the past, the film seems to imply that reformation, too, has ethical limitations.

Another scene concerns the theme of liberation, or more specifically, “pharmacoliberation,” which refers to the freedom to use pharmacal means to maintain and/or alter one’s hormone levels. In this scene, a circle of trangender individuals share a tube of hormones with Orlando outside of the doctor’s office without the doctor’s approval. The scene challenges medical authority in setting thresholds for transgender individuals’ gender affirming surgeries, a hindrance for many trans individuals today. The scene is also a stylistic break from many other scenes: it contains use of club music instead of regular diegetic sound, with lyrics referring to sexuality-focused modern and postmodern theorists such as Freud and Lacan.

Following this versatile scene is a vertically downward exploration of erased queer history – to write a biography is to “descend to the realm of the dead.” In a narrow, dimly lit space, Orlando shares that they have a rage within that pushes them to speak up for transgender and nonbinary individuals’ encounters today, and the act of sharing and storytelling is what makes them joyful and fulfilled. Orlando, after gender transformation, went into an arm shop and realized that men do not only have the right to use violence but are obliged to use it, while women are expected to disarm. The scene ended with Orlando trading a 18th Century gun for a toy fox — “Volumia Fox.”

Towards the end, the film delves into some contemporary topics including coloniality, race and the concept of citizenship. The film juxtaposes scenes redesigning the book Orlando, where people substitute photos of Orlando with photos of today’s children to showcase some encounters Orlando may have today. Certain historical discourses require intervention: One of the portrayals of Orlando in a colonial city whitened their face, just as people in colonies do to distinguish the imperial from the subaltern. One Orlando, who cannot obtain a valid passport as a transgender individual, was dismissed from a lodge and later went to court to demand equal rights. Sitting together in the court, the Orlandos await for the final judgement of a fictional trial.

The film ended with a humorous, positive note: with the “power given by Virginia Woolf and literature,” the judge granted nonbinary and transgender individuals citizenship, delivering passports across the court. The passport signifies an acknowledgment of contemporary Orlandos’ identities – that they could be finally treated as a regular citizen and have claims to all rights given by the constitution and that they are no longer invisible, or negligible, and no longer dehumanized, firmly claiming back their lives as human beings.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Tina Qian is a Trinity sophomore and an arts editor for Recess.