For the last five months, the Nasher was home to two new exhibits that, while small in size, carry a message of great importance. “Processing Systems: Numbers” by Sherrill Roland and “Seeing from the Block: Observing the Justice System” through the Collection of the Nasher Museum examine the criminal justice system, with a focus on innocence and the experience of life behind bars.

Innocence in the criminal justice system is a topic of deep personal interest to Sherrill Roland, who was himself wrongfully incarcerated. While he was later exonerated, the experience consumed three years of his life and left him determined to refocus his existing art career on the criminal justice system and its flaws.

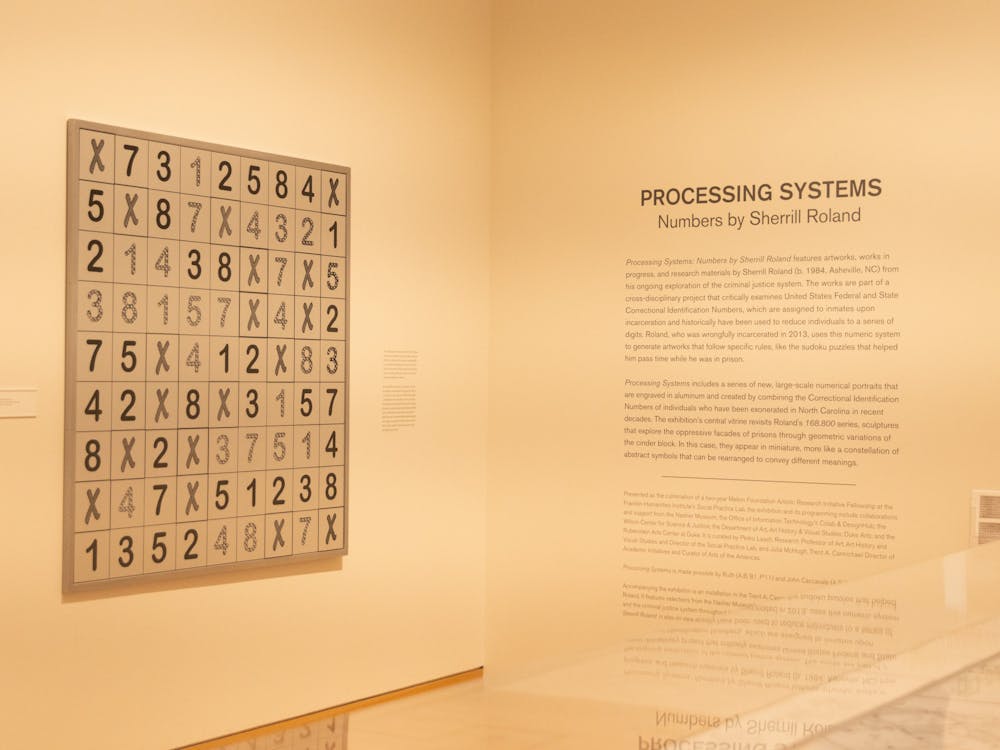

The exhibit centers on two themes. The first is Correctional Identification Numbers: eight digit numbers — with the first five representing the inmates case number and the final three representing their state — that are often used in place of a prisoner’s name, dehumanizing and anonymizing them. Roland turned this anonymity into a way of telling the stories of exonerated individuals without exposing their identities, helping protect them from the baggage that often follows even exonerated former inmates. The numbers are turned into large Sudoku-esque displays etched into aluminum, titled with the number of days these individuals spent in prison and hung on the walls of the gallery.

In the gallery’s center and on a wall off to one side, visitors see the second component of the exhibit: cells. Roland has laser-etched paper modeled after the cells of a prison, with colored geometric patterns highlighting the different patterns formed by the cinder blocks that made up the cells. These same patterns are displayed in a case at the center of the exhibit, rendered as 3D-printed patterns rather than etched drawings. It functions as a new version of Roland’s “168.800” series of sculptures, which were made of steel and Kool-Aid.

The exhibit represents the culmination of a two-year Mellon Foundation Artistic Research Initiative Fellowship. This Fellowship was awarded to the Franklin Humanities Insitute’s Social Practice Lab, which convenes scholars, artists and community members to create art focused on social issues, fostering collaboration and conversation. Roland worked with the Social Practice Lab as part of the fellowship, though the project also drew on other departments. The Wilson Center for Science and Justice, which uses science to inform legal policy, helped him research the cases of other wrongfully convicted individuals. Duke’s Innovation Co-Lab also contributed to the exhibit — their first ever Nasher contribution — by fabricating the different exhibit components.

Roland also drew on the archives of the Nasher Museum for inspiration, leading him to curate a second exhibition, “Seeing from the Block: Observing the Justice System through the Collection of the Nasher Museum.” This companion showcases the art pieces he found most impactful. The pieces shown are a mixture of photographs and drawings, focusing on individuals connected to the justice system, including prisoners themselves.

While small, Roland’s exhibit is phenomenal, transforming everyday items into a powerful and understated commentary on prison and life behind bars. All we know about the individuals represented is their prison sentences, ranging from 2484 days (approximately 6.8 years) to 8028 days (approximately 22 years). This highlights the profound cost of wrongful conviction and sparks reflection on the broader implications of our current legal system. The artistic representations of prisoner cells provide glimpses into the lives of those affected.

Roland’s other exhibit is equally compelling, though in different ways. It emphasizes the same flaws of living in prisons while also showing us some of the works that inspired Roland’s exhibit. Most art is best considered as part of a conversation with existing works — whether as inspiration or response — and it is always wonderful to see the specific works an artist engaged with.

The exhibit also highlights the depth of talent at Duke and in Durham, as well as the tremendous power of arts-related collaboration, especially between arts and non-arts departments. It is reminiscent of the current library exhibit and is something that arts organizations at Duke should pursue more often.

While this exhibit is no longer at Duke, there are plenty of wonderful art exhibits on campus and in Durham. More importantly, students and artists at Duke can learn valuable lessons from the example it set.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Zev van Zanten is a Trinity junior and recess editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.