Editor’s note: This article is one in a five-part series looking back on the life of one of Duke’s most infamous alumni — Richard Nixon. Read the following installments recounting Nixon’s introduction to the political spotlight, his road to the White House, his tumultuous presidency and his eventual fall from grace, which will be published over the next week.

Hannah Nixon was baking pies one afternoon in 1934 when her son burst through the door, an open admissions letter addressed from Durham in his hand. In a 1960 interview, she called it “the proudest day of my life — yes, even prouder than the day Richard became vice president.”

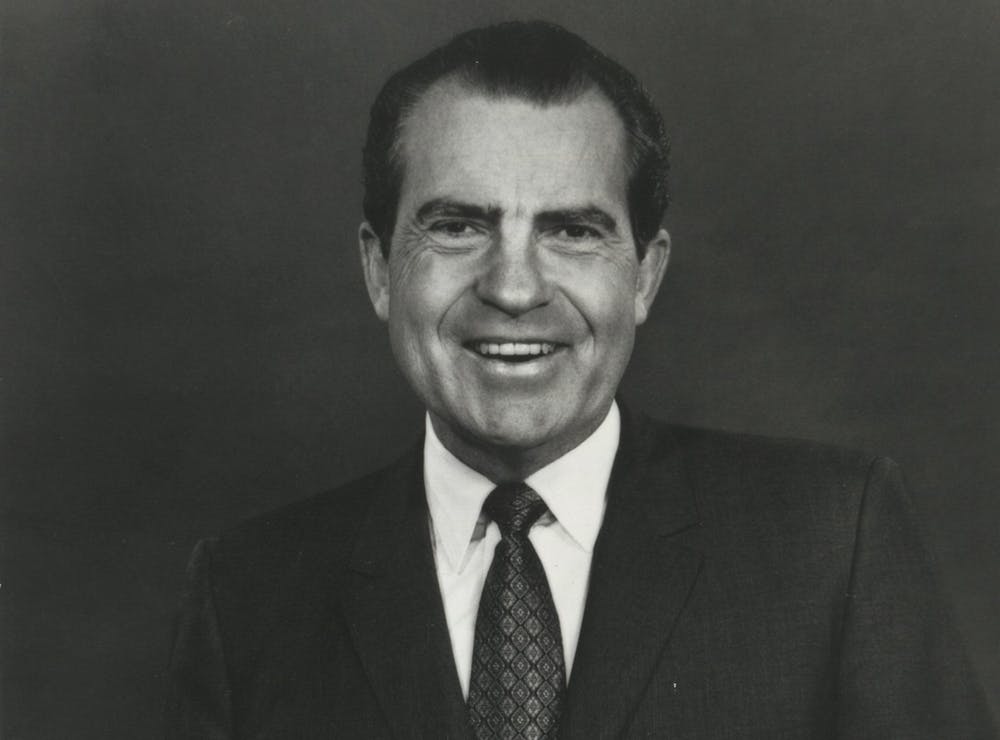

Richard Milhous Nixon, Law School ‘37, is the only U.S. president Duke has produced in its century. “Few came so far, so fast, so alone,” biographer John A. Farrell wrote about the man who graduated Duke at 24, became a congressman at 34, a senator at 38, a vice president at 40 and a president at 56.

The Duke alumnus’s historic trip to China in 1972 redefined U.S. foreign policy and opened diplomatic relations between the two nations. Domestically, his administration created the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, signed off on Title IX and launched the war on cancer.

Still, the scandals that bear his name overshadow his achievements. Only a few years after he won the largest share of the popular vote for the Republican Party in any presidential election, he left office in the face of the Watergate scandal. Behind closed doors, Nixon was an obsessive racist, homophobe and antisemite. His efforts to bomb Cambodia and extend the Vietnam War for political gain destroyed the lives of tens of thousands in Southeast Asia, both directly and indirectly, and his record on civil rights as a congressman and vice president is undermined by his manipulation of racial tensions in the South for electoral benefit.

The Duke alumnus sprung into the national spotlight by laying the foundation for the McCarthy era and left it as the only president in American history to resign in disgrace, in the process giving rise to the suffix "-gate” now used to mark scandals of every stripe. Historians consistently rank Nixon in the bottom half of U.S. presidents.

Since the Watergate scandal, Duke has attempted to distance itself from Nixon. Little has been said about the University’s arguably most (in)famous alumnus during its Centennial celebrations. The year Nixon resigned in disgrace, his portrait was stolen and stuffed in a second-floor classroom, prompting the Law School to remove it from its library, then return it decades later. The Nixon Presidential Library, now located on the grounds of his childhood home in California, stands far from the University, where its establishment was once proposed and subsequently rejected by Duke faculty.

And yet, the shadow of Duke’s most contentious alumnus lingers quietly, the pall of a man who was always striving, never secure, rarely satisfied and often cruel.

The laughs, slights and snubs

Richard Nixon was born Jan. 9, 1913, to Frank and Hannah Nixon on the family’s lemon ranch in Yorba Linda, California. The ranch went bust when Richard was nine years old, and the Nixon family moved to Whittier, California, where Frank started a combination grocery store and gas station.

Nixon’s childhood was characterized by labor. The Quaker boy who would help Frank hoe weeds at the lemon ranch became a high schooler who would study until midnight and wake up at 4 a.m. to buy fresh groceries at the Los Angeles markets. Nixon recalled that his family “never had any vacations … We never ate out — never. We certainly had to learn the value of money.”

“Gloomy Gus,” as his peers came to call him, was shy and awkward in conversation, often coming off as disinterested and brooding. Nixon was insecure — about his intellect, about his socioeconomic status — but he suffocated his anxieties with aggression and ambition. He confided only in his mother and brothers.

Part of him wanted to be liked, but he was not easy to get close to. His extreme introversion left many to guess that he was awkward at best and a sanctimonious prude at worst. Emotionally isolated yet deeply sensitive, he was aware of his “unlovable” reputation, equally resentful and proud of it.

“What starts the process, really,” Nixon told an aide later in life, “are the laughs and slights and snubs when you are a kid … But if you are reasonably intelligent and if your anger is deep enough and strong enough, you learn that you can change those attitudes by excellence, personal gut performance while those who have everything are sitting on their fat butts.”

* * *

In 1925, Richard’s younger brother Arthur Nixon complained of a headache. A few weeks later, he was dead. What the Nixons first suspected was indigestion was later diagnosed as tubercular meningitis, and Richard, then 12 years old, “slipped into a big chair and sat staring into space, silent and dry-eyed in the undemonstrative way in which, because of his choked deep feeling, he was always to face tragedy,” in the words of his mother Hannah.

Two years later, Richard’s older brother, Harold, began coughing up blood. It would take six years for him to die of tuberculosis.

Nixon bounced between Whittier and Fullerton Union High School in the meantime, graduating third in his class from Whittier in 1930. An involved student, he took the leading roles in plays, ran a failed campaign for student body president and became a champion debater. By forcing himself onto the stage, Nixon sought to make up for his inability to make small talk.

Harvard and Yale courted him with partial scholarships, but Harold’s treatment left the Nixon family financially unstable. Unable to pay for transportation and boarding on the East Coast, Nixon attended the nearby Whittier College instead.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Harold’s death struck the Nixon family in the spring of Richard’s junior year at college. Richard, now 20 years old, locked his grief inside of him once again. His mother remembered that he “sank into a deep, impenetrable silence,” as he did when Arthur died.

“From that time on, it seemed that Richard was trying to be three sons in one, striving even harder than before to make up to his father and me for our loss,” she said. “… Unconsciously, too, I think that Richard may have felt a kind of guilt that Harold and Arthur were dead and that he was alive.”

Still, Richard excelled at Whittier. He graduated second in his class and was elected student body president his freshman and senior years. Students from the men’s society he helped found and the football team he warmed the bench on wrote nice things in his yearbook. Although he was popular, Nixon had few friends — classmates would remember him as “brilliant” but “too stuck-up.”

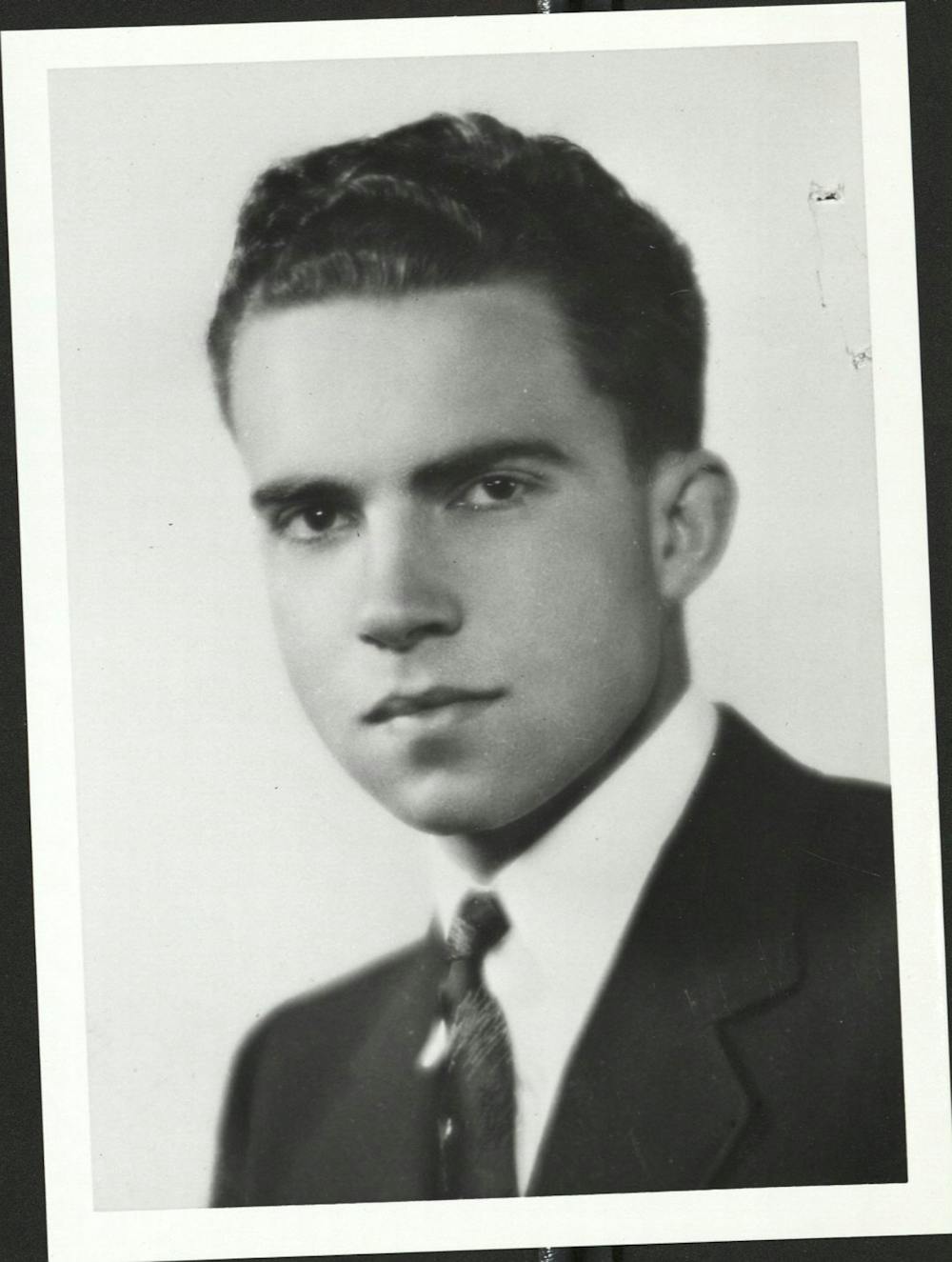

In spring 1934, Nixon applied to Duke Law School, attracted by the generous scholarships made possible by James B. Duke’s endowment. Faculty members wrote him glowing recommendations. Albert Upton, drama coach and chairman of Whittier’s department of English, praised Nixon’s “human understanding, personal eloquence and marked ability to lead,” while Whittier College President Walter Dexter wrote that he believed Nixon “[would] become one of America’s important if not great leaders.”

Nixon was not used to joy — but when a letter from North Carolina arrived with a $250 full-tuition scholarship in tow, he was a different man.

“The night he found out,” his college girlfriend remembered, “oh, we had fun that night. He was not only fun, he was joyous, abandoned — the only time I remember him that way. He said it was the best thing that ever happened to him. We rode around in his car and just celebrated.”

The ‘meat grinder’

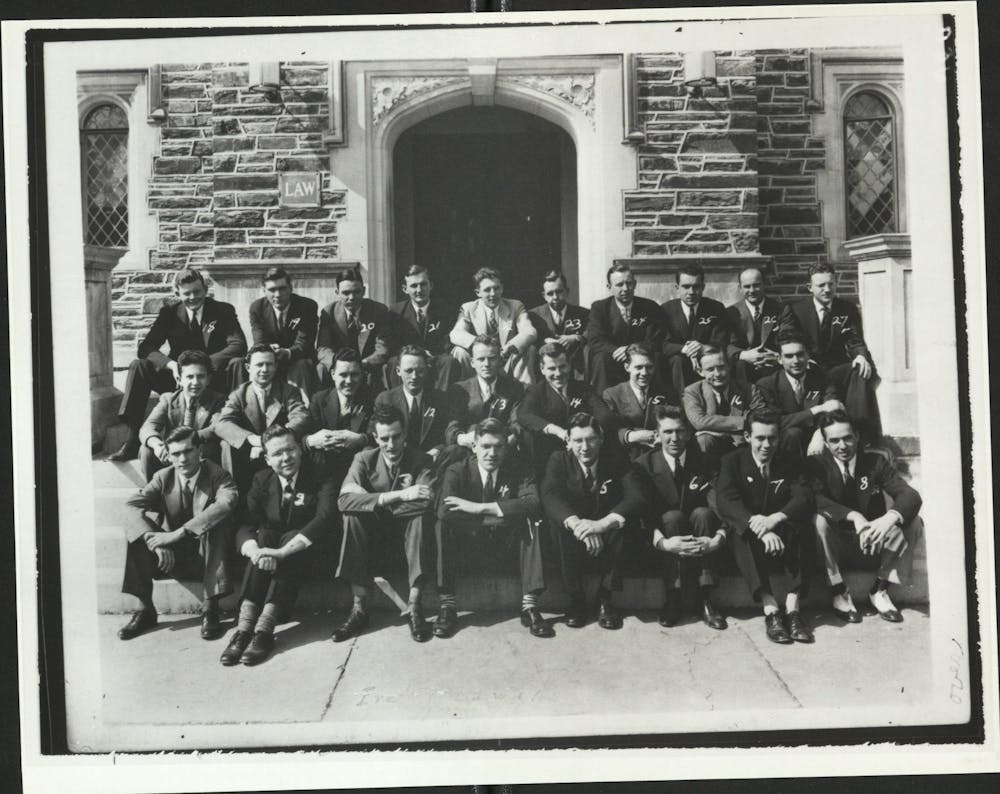

But Nixon carried his worries to law school, compounded by his financial insecurity. In order to keep his scholarship, he needed to maintain a B average. Students called the scholarship program “the meat grinder” — of the 25 first-year scholarships offered to his 44-member class in 1934, only 12 would be renewed the following year.

Through great trial, Nixon would keep his scholarship for all three years and eventually graduate third in his class.

Anxious and insecure, he would get up at 5 a.m., study until classes began, work at the library and study again until midnight. His classmates admired his dedication and laughed at how seriously he took himself, and “Gloomy Gus” with the “iron butt” that allowed him to read for hours was elected president of the Duke Bar Association during his second year.

“He never expected anything good to happen to him or anyone close to him which wasn’t earned,” said classmate Lyman Brownfield. “Any time someone started blowing rosy bubbles, you could count on Nixon to burst them with a little sharp prick.”

Still, his time at Duke added character beyond his pessimistic persona. Nixon maintained a Spartan lifestyle and kept his schedule packed, as he did at Whittier. His first year at Duke, he lived in an abandoned tool shed before moving into a rented room with a roommate, showering on campus and hiding his shaving kit in the library because he had no indoor plumbing. The law student rarely smiled but showed quiet kindness. Joseph S. Hiatt, Jr., a medical student at the time, recalled how Nixon would often carry law student Fred Cady, a polio victim, up the stairs to the law school.

Other stories were more colorful. In an anecdote exhumed during the Watergate scandal, Nixon and two classmates broke into the dean’s office to see their class standings after grades were delayed. One classmate recalls him standing on a picnic table after drinking three to four beers — something he never did at Whittier and rarely indulged in at Duke — and giving a speech titled “Insecurity,” when he “managed to get everything about Social Security so tangled up and backwards that he sounded like Red Skelton.” He left his classmates in stitches, and throughout graduation week, they would unsuccessfully try to convince Nixon, now sober, to make more funny speeches.

After falling short in his job search on Wall Street and at the FBI, Nixon returned to California after graduation and became the first Duke graduate to take the California bar exam, passing on his first try. He settled into life as president of the Duke University Alumni of California and lawyer at Wingert and Bewley, and later as husband of Thelma “Pat” Ryan.

Years later, after he made the eventual switch from law to politics, Nixon would campaign for president in Greensboro, saying that he “owe[d his] education to North Carolina and to Duke University.”

“I remember that I worked harder and learned more in those three years than in any three years of my life,” he said. “And I always remember that whatever I have done in the past, or may do in the future, Duke University is responsible one way or the other.”

Editor’s note: Much of the information for this article was sourced from Farrell’s 2017 book “Richard Nixon: The Life” and Stephen E. Ambrose’s 1987 book “Nixon, Vol. 1: The Education of a Politician, 1913-1962.”

Audrey Wang is a Trinity senior and data editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume. She was previously editor-in-chief for Volume 119.