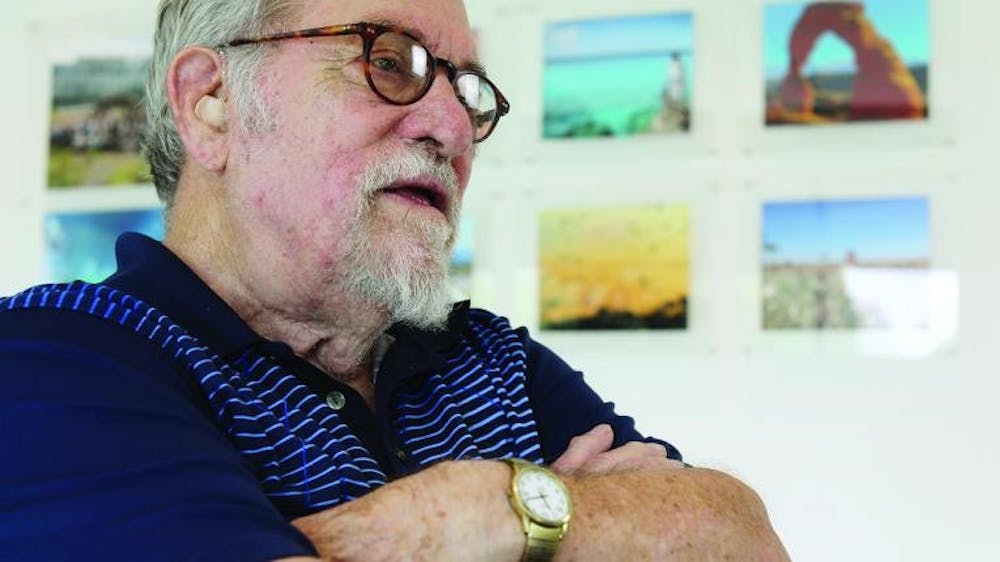

Orrin Pilkey, James B. Duke professor emeritus of geology, is remembered as a longtime advocate for research-informed coastal management, a nationally recognized science communicator and a unifying figure in Duke’s geology department.

Pilkey, 90, died Dec. 13 of natural causes in his Durham home. Once named the “reigning dean of American coastal studies” by The New York Times, he had a profound impact on the field of geology and coastal policy in North Carolina and beyond, as well as at Duke, where he worked for nearly 60 years.

“Orrin was just a force,” said Stuart Pimm, Doris Duke professor of conservation ecology in the Nicholas School of the Environment. “… He told truth to power in a very effective and very forthright way, and one has to admire him for that.”

Pilkey was born Sept. 19, 1934, in New York City to Elizabeth and Orrin Pilkey Sr., but he spent most of his childhood in Richland, Washington, where his father worked as an engineer at the Hanford plutonium plant. It was there, “romping and roving along the banks of the Columbia River,” where Pilkey first developed a deep affinity for the natural world that would last a lifetime.

He spent five summers as a smokejumper for the Forest Service in Oregon, Idaho and Montana before enrolling at Washington State College. Pilkey received his bachelor’s degree in geology from the college in 1957 and a master’s degree in the same subject from the University of Montana in 1959. After a brief stint in the U.S. Army, he earned his doctorate from Florida State University in 1962, again in geology.

For three years, Pilkey worked as a research professor at the University of Georgia Marine Institute on Sapelo Island. Then in 1965, he joined Duke’s faculty to study deep-sea sediment deposits from aboard the University’s new vessel, the Eastward.

According to Robert Young, Graduate School ‘95 and one of Pilkey’s former students, Pilkey spent his early career doing “basic marine geology research.” He was well respected in the field, earning the Francis P. Shepard Medal for Excellence in Marine Geology in 1987 and the James H. Shea Award for Excellence in Earth Science Writing and Editing in 1993.

But four years after Pilkey joined Duke’s faculty, Hurricane Camille swept across the Gulf South as a Category 5 storm in August 1969, wreaking mass devastation and flooding his parents’ Mississippi home.

“It was my ‘a-ha’ moment,” he later told Duke. “The destructive power of that storm made me realize I could apply my expertise on sediment transport to something that could make a real difference in the lives of millions.”

From then on, Pilkey was an ardent advocate for better coastal management strategies backed by science.

As shorelines across the country began to recede, many coastal communities at the time were attempting to protect themselves from eventually being washed away. The two most common approaches to combating erosion were building seawalls — concrete structures meant to block the waves — and adding more sediment to the coast to compensate for lost sand in a process known as beach nourishment.

However, a growing body of research showed that such efforts could be damaging to the environment by disrupting habitats and natural water flow patterns, as well as by intensifying erosion in areas outside of the protected boundary. Moreover, they were an expensive and unreliable long-term solution.

Pilkey pointed out that such erosion was actually a natural process better characterized as “shoreline retreat” and that human attempts to stall that process ran counter to the inherently dynamic nature of barrier islands and other coastal regions.

“… [I]f we don’t want [barrier islands] to move because we build on them, then we’re going to have to be continually trying to stop them from moving by engineering,” said Marine Lab Director Andrew Read. “And that’s a battle — Orrin would say — we are destined to lose.”

But it wasn’t enough to do the research. Those findings had to be shared with the people actually making the decisions about how the nation’s shorelines should be managed.

So, Pilkey brought the information to policymakers.

While still teaching at Duke, he attended hundreds of town halls and state legislature meetings to make his case against further investment in ill-advised coastal management strategies. He also penned numerous op-eds to raise the profile of his campaign and share his message with the broader public.

“He took a lot of information from the science, from what he had learned over the 40 [or] 50 years … and then was basically able to demonstrate to the policymakers that these were very poor decisions — things [like] hardened structures and rock walls and these jetties that they put out [had] destroyed these barrier islands,” said Curt Richardson, research professor of resource ecology in the Nicholas School. “So he was able to change the whole narrative on coastal communities.”

Pilkey’s hard work paid off.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

In 1974, the N.C. General Assembly passed the landmark Coastal Area Management Act, which established a system to regulate development in coastal areas. Then in 1985, the N.C. Coastal Resources Commission banned oceanfront seawalls throughout the state, a decision that became law with a unanimous vote from the NCGA in 2003. South Carolina did the same a few years after North Carolina’s initial move with the Beachfront Management Act in 1988.

But he didn’t stop there. Although Pilkey advocated for the state to stop pursuing coastal management strategies he viewed as doomed to fail, he understood the desire to protect existing structures from the ocean’s erosive forces. He was particularly concerned about the historic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, located on the barrier island of the same name, which was at risk of being destroyed.

Pilkey campaigned to move the structure — originally built in 1803 and completed in its current form in 1870 — 2,900 feet inland to a more stable site, where its foundation would be better protected. Despite facing significant community pushback, Pilkey’s argument was supported by an independent study, and the lighthouse was relocated in 1999. Standing at 198 feet, it remains the tallest lighthouse in the United States.

“It’s a spectacular thing for him to have done,” Pimm said.

In 2000, Pilkey received the Geological Society of America’s GSA Public Service Award in recognition of his influential advocacy work, and he was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award from the N.C. Coastal Federation in 2008.

Although his impact on coastal policy was undoubtedly significant, some remember Pilkey more for his “larger-than-life” personality.

Richardson first arrived at Duke in 1978. At that point, he recalled that Pilkey was already a “fixture” at the University.

“He was probably one of the most loved professors in the Nicholas School,” Richardson said.

Pilkey taught many of his courses from the University's Marine Lab in Beaufort, where he was known for his field trips that brought students out onto the shore — and sometimes the water — to get hands-on experience with the processes they learned about in the classroom.

The “frontline scientist,” as Richardson called him, built a close relationship with his students and was remembered as a central figure in his department.

“He was a hell of a lot of fun,” Young said. “… The social life of Duke geology sort of revolved around his house in Hillsborough.”

Young first met Pilkey in 1987, when he applied to Duke’s master’s program in geology. Though he ultimately decided to enroll at the University of Maine, Pilkey kept in touch with the young geologist, writing to him about developments in the field and sending newly published papers.

When Young completed his master’s degree in 1989, Pilkey told him to come to Duke for his doctorate. So he did.

Young remembered attending what seemed like “dozens of parties” every year at the Pilkeys’ house, where Orrin and his wife Sharlene hosted viewings of Duke basketball games and other major sporting events. Young described the two as “uniquely generous people” who “opened their doors to everybody” — not just Pilkey’s own students, but the entire department.

Pilkey was also an influential figure on the academic side. In 1986, he founded the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Duke, which “advocate[s] for responsible management policies” that aim to “balance economic and environmental interests” at the nation’s coasts. Pilkey remained director emeritus of the program until his death, even after it moved to Western Carolina University over a decade ago, where Young now serves as its director.

In 2014, the Duke Marine Lab honored Pilkey by dedicating its newest research building as the Orrin Pilkey Research Laboratory. It is located on Pivers Island, an inner island on the N.C. coast that is protected naturally from coastal erosion by outer barrier islands.

Even after he stopped teaching, Pilkey continued to write and advocate for more responsible coastal management strategies, which remains an ongoing issue on the North Carolina coast. Over the course of his career, he published over 250 scientific papers and 49 books about coastal erosion and sea-level rise, in addition to various op-eds against policies he viewed as problematic.

“Orrin really believed it was a scientist’s responsibility to get involved in management and policy,” Young said. “Too often, academics feel like you’re compromising yourself as a scientist if you get involved in advocacy, but … Orrin believed that it’s your duty not just to publish something … but … to go out there and serve on public bodies, to talk to people about the science [and] to communicate it in a way that people would understand.”

Pimm emphasized “how much of an inspiration he was for all of us who speak out on environmental issues that are sometimes very, very unpopular.”

“Science needs a voice. We need to share what we know, and that’s what I try to do,” Pilkey once said. “These beaches don’t belong to the people who have chosen to build structures there. They belong to our children and grandchildren. What a tragedy it would be if we let them be destroyed because we didn’t speak up and share the truth.”

Editor’s note: To plant a memorial tree in honor of Pilkey, visit the link here.

Zoe Kolenovsky is a Trinity junior and news editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.