Editor’s note: This article is one in a five-part series looking back on the life of one of Duke’s most infamous alumni — Richard Nixon. Read the previous installment on his childhood and stint as a Blue Devil, with additional articles recounting his road to the White House, his tumultuous presidency and eventual fall from grace to be published over the next week.

‘I had to win’

“Of course I knew Jerry Voorhis wasn’t a communist,” Richard Nixon said. The young congressman was musing over his recent campaign with his defeated opponent’s adviser over lunch in 1947. “But … I had to win. That’s something you don’t understand. The important thing was to win.”

* * *

Gen. Douglas MacArthur was drafting a new constitution for Japan, and Joseph McCarthy was calling his 1946 Senate opponent a communist in Wisconsin. Back in California’s 12th Congressional District, House Democrat Jeremiah “Jerry” Voorhis was running for his sixth straight term. Republicans were desperate for a candidate who could put up a fight against the incumbent, and when the Committee of 100 — a political network — came across a 33-year-old who promised to “tear Voorhis to pieces,” they struck gold.

Exactly why Nixon decided to leave his law career behind and enter the political ring is unclear, though his long-held desire to outgrow his humble beginnings was likely a factor. Regardless of his personal motives, the young upstart seemed to be exactly what the GOP was looking for.

“This man is salable merchandise,” said committee chair Roy Day.

That merchandise had returned from World War II as a lieutenant commander, having earned anywhere from $3,000 to $10,000 earned in poker. Nixon’s men and superiors in the Navy liked him for his diligent logistics work, but there were no heroics — he later wrote in his memoirs that “the only danger came from a few straggling snipers and the ever-present giant centipedes.”

At his campaign kickoff rally, Nixon emphasized his outsider status.

“I want you to know that I am your candidate primarily because there are no special strings attached to me. I have no support from any special interest or pressure group. I welcome the opposition of the PAC, with its communist principles,” he said.

But which PAC?

When people heard “PAC” in 1946, their minds were immediately drawn to the Congress of Industrial Organizations Political Action Committee, which had several openly communist members. Voorhis steered clear of the hardliners from the CIO-PAC, but he also received an endorsement from the National Citizens Political Action Committee, a separate group that was a CIO-PAC offshoot. Nixon’s campaign sought to blemish Voorhis’ reputation by merging the two PACs into one “communist-dominated PAC.”

When Voorhis asked that he provide “proof” of an endorsement from said “communist-dominated PAC” at a debate, Nixon brandished a preliminary list of endorsements from a local NCPAC chapter. And when Voorhis sputtered that they were different groups, Nixon read the names of the NCPAC and CIO-PAC leaders out loud. With so many similar names, he concluded, the PACs were one and the same.

For the Nixon team, it didn’t matter which PAC the candidate was referring to, as long as he kept saying “PAC.” And it didn’t matter that Voorhis abhorred communism and would not accept PAC endorsements unless they renounced communism, as long as the Nixon team could run ads that read:

“A VOTE FOR NIXON IS A VOTE AGAINST THE COMMUNIST-DOMINATED PAC WITH ITS GIGANTIC SLUSH FUND.”

“PAC LOOKS AFTER THE INTERESTS OF RUSSIA.”

“REMEMBER, Voorhis is a former registered Socialist, and his voting record in Congress is more Socialistic and Communistic than Democratic.”

The Voorhis campaign was poorly organized and could not defend itself against the young upstart. When Nixon attacked Voorhis for failing to enact any of his bills in the previous four years, save a law on rabbit farms, Voorhis stuck to the four-year time frame Nixon outlined and did not point to his prior six years in office or the Voorhis Act of 1940 — or the fact that members of Congress rarely got their names on bills. Instead, he weakly explained congressional procedure and threw credit to a colleague for actually introducing the rabbit bill. He simply added an amendment.

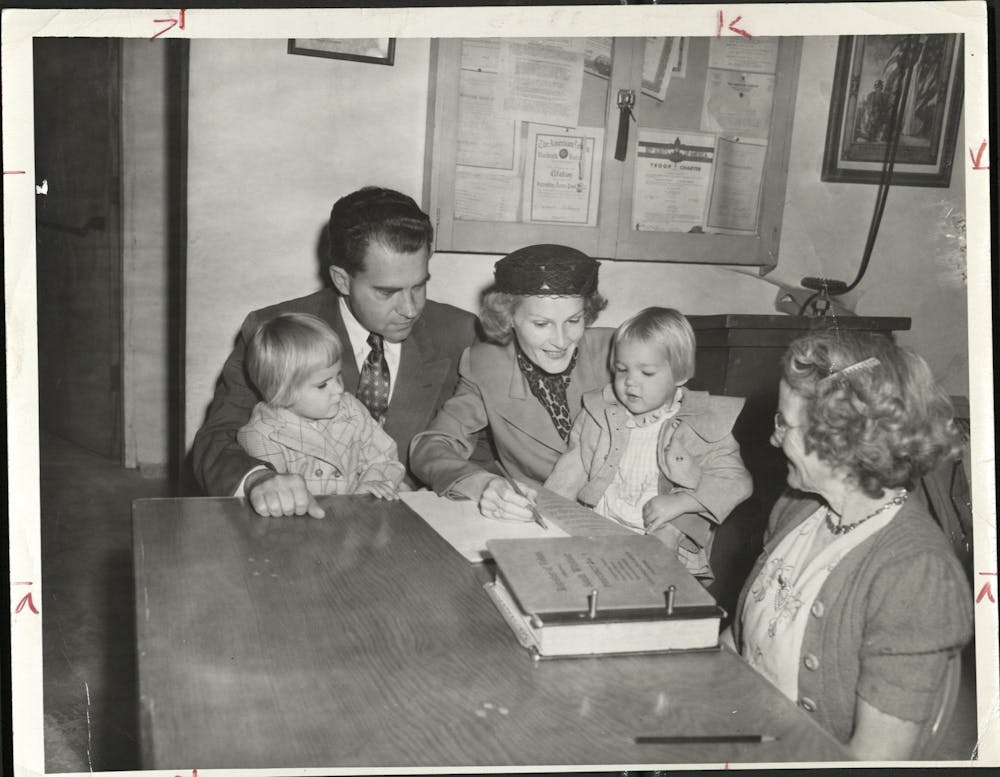

It’s easy to see why Nixon campaigned the ruthless way he did. He had a pregnant wife, limited campaign funds and no incumbent status. He had auditioned before the Committee of 100 in the only good suit he had — his Navy uniform — and gambled half of his and Pat’s personal savings on the campaign. Older and more seasoned Republicans egged him on: “Nice guys and sissies don’t win elections,” Day often said.

Most importantly, Nixon wanted to win.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Win he did. He felt he had to. The 33-year-old sailed to victory with 56% of the vote. For some who knew him growing up, this was a “new Nixon.” He wasn’t just being competitive or resourceful, as they knew he could be. He was playing dirty.

“Real Quakers look at men with a level eye,” one former classmate said about the 1946 election. “Dick Nixon doesn’t.”

* * *

By 1948, Nixon had established himself as an impressive freshman congressman. He maintained a close connection with his constituents, spending nearly a month in the 12th district selling the Marshall Plan and writing a weekly column for the district’s newspapers. They rewarded his efforts with both the Republican and Democratic nominations when he cross-filed in June.

Reporters liked him too. Newsweek described Nixon as “youthful and intensely sincere,” and when he asked questions at House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings, The New York Times praised his “considerable reputation for fairness to witnesses.”

By the end of the year, Nixon’s honeymoon with the press would come to a sudden and decisive end.

In August, one Whittaker Chambers appeared before the HUAC and accused Alger Hiss, then president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, of being involved in the communist spy ring Chambers had previously led.

Hiss was a Johns Hopkins and Harvard Law School alumnus who clerked under Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Handsome and eloquent, Hiss was “everything that an elegant Washington executive should be in the New Deal era,” Nixon remembered.

He came before the HUAC to clear his name, and it almost worked. Hiss charmed the small crowd, and Nixon recalled “Hiss’ friends from the Georgetown” laughing as the accused smiled back at them “in a very satisfied cat-that-swallowed-the-canary manner.” By the end of the session, President Harry Truman was quoted agreeing that the HUAC hearing was a “red herring,” and everybody in the HUAC was tempted to pass the case on to the Department of Justice.

Everybody except for Nixon.

Nixon would later say that he knew Hiss was bluffing during his testimony. The truth was that John Cronin, an anti-communist priest, had tipped Nixon off in early 1947 about Hiss’ Communist past.

And Nixon simply did not like the man. There was something about Hiss that was “too smooth,” he told the HUAC committee members. He felt that the Ivy Leaguer looked down on the committee as “bumbling know-nothings who, in the minds of intellectuals and particularly the diplomatic set, generally inhabit the Congress.”

He was “insolent,” Nixon said. “Almost condescending.” For the young congressman who had willed himself to Washington because his anger was deep enough and strong enough, Hiss — with his Harvard education and Supreme Court connections — was “insulting to the extreme.”

Motivated by personal dislike, Nixon threw himself into the Hiss case. He sleeplessly hammered away at Hiss’ testimony until The New York Times ran the headline: “ALGER HISS ADMITS KNOWING CHAMBERS.” HUAC investigators received microfilm evidence — later known as the Pumpkin Papers — that both Chambers and Hiss were Communist spies, and a grand jury eventually voted unanimously to indict Hiss on two counts of perjury (the three-year statute of limitations on espionage had passed).

Nixon later wrote that he was “subjected to an utterly unprincipled and vicious smear campaign.” The Hiss case had made him a household name, but it also branded him as a marked man for the “educated, progressive middle class, especially in its upper reaches,” wrote literary critic Lionel Trilling. Even his allies saw him as an opportunist who would do anything for a headline.

As emotional, as green and as private and sensitive as he was, Nixon could not help but gnaw at his wounds. He began to hate them — the press, the Ivy Leaguers, the elitists, the liberals — those who had subjected him to such baseless slander when, in his mind, he was only doing his duty.

Nixon would later say that he “won the Hiss case in the papers,” that he had to “leak stuff all over the place” and that he “had Hiss convicted before he ever got to the grand jury.” He received word of the Pumpkin Papers not from his HUAC colleagues, but from Bert Andrews, the bureau chief of the Herald Tribune. In his telegram to the young congressman, Andrews wrote:

“DOCUMENTS INCREDIBLY HOT. LINK TO HISS SEEMS CERTAIN … MY LIBERAL FRIENDS DON’T LOVE ME NO MORE. NOR YOU. BUT FACTS ARE FACTS AND THESE ARE DYNAMITE.”

“The Hiss case just stayed with him and never went away, and the wounds and the feeling about the press that happened there are very basic to him,” Nixon’s aide Robert Finch said. “There was, for a long time, a corrosive effect. And there was genuine anger there, I mean real anger … real hostility, something that went so deep as to make a man embattled.”

Playing Checkers

China was Red, the Soviets tested their first nuclear bomb and American boots landed in Korea. McCarthy warned of “enemies from within,” and Nixon launched his 1950 Senate campaign against incumbent Helen Douglas, whom he soon started calling “the pink lady” to imply that she was a lighter shade of Communist red.

“Pink right down to her underwear,” Nixon liked to say.

The Nixon team copied the playbook from 1946. They distributed pink sheets comparing Douglas to Vito Marcantonio, “the notorious Communist party-line congressman from New York.” The Nixon campaign ran ads too: “If you want to work for Uncle Sam instead of slave for Uncle Joe, vote for Dick Nixon. Don’t be left, be right, with Nixon. Don’t vote the Red ticket, vote the Red, White and Blue ticket. Be an American, vote for Nixon.”

“If there is a smear involved, let it be remembered that the record itself is doing the smearing,” Nixon said. “Mrs. Douglas made that record. I didn’t.”

But the Nixon campaign didn’t restrict itself to smears on Douglas’ congressional record. The campaign also directed its attention to her husband, Melvyn Douglas — a Jewish man who changed his last name from Hesselberg for his acting career. Nixon supporters like far-right populist Gerald L.K. Smith encouraged voters to reject the woman “who sleeps with a Jew.” Though the Nixon campaign distanced itself from Smith, Nixon would often, allegedly accidentally, slip and call Mrs. Douglas “Mrs. Hesselberg” at rallies.

Richard Nixon would later apologize for how he carried his Senate campaign as he geared up for the 1960 presidential election. “I’m sorry about that episode,” he said in 1957. “I was a very young man.”

But for 37-year-old Nixon, that’s what you had to do to win in politics. He won 59% of the vote and a little extra — the nickname “Tricky Dick,” which followed him for the rest of his career.

Douglas did not congratulate him in her concession speech.

* * *

It only took five years for Tricky Dick to become one of the Republican Party’s foremost leaders warning against the dangers of communism and criticizing Truman’s foreign policy. He maintained a friendship with McCarthy as a fellow former HUAC member but kept a polite distance from his more extreme accusations. Eloquent, energetic and young, Nixon was popular among Republicans. When Dwight Eisenhower tapped him for vice president, it seemed like a perfect match.

That was until The New York Post ran the headline: “Secret Nixon Fund: Secret Rich Men’s Trust Keeps Nixon in Style Far Beyond His Salary.”

Over the years, Nixon had accepted contributions to help him pay for mailings, printing and travel that exceeded his expense allowance. The practice was not illegal, nor was it uncommon. Compared to other high-profile politicians, Nixon’s $18,000 fund — roughly $190,000 today — can even be called conservative. Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson had an $84,000 slush fund at the time, and Eisenhower himself received lavish gifts, including a house at the Augusta National Golf Club.

But the headlines focused on Nixon, and soon began a hellish weekend for the vice presidential hopeful. At campaign stops, protesters met him by throwing coins and holding signs that read "Pat, What Are You Going to Do With the Bribe Money?" Newspapers including The Washington Post and New York Herald Tribune called for Nixon to step down as Eisenhower defended his vice presidential candidate against a divided campaign team.

Nixon told Eisenhower that he would step down if he said so, but the presidential candidate needed more time. Nixon would instead undergo a full financial audit and give his side of the story at a television broadcast that week — embarrassing for anyone, but especially degrading for someone as private and sensitive as he was.

Less than an hour before the broadcast, Nixon received a message from a group of Eisenhower’s top advisers. After the broadcast, they decided that Nixon should submit his resignation. Nixon, defiant, told them “they had better listen” and hung up the phone.

A record 58 million people gathered in their living rooms and watched Nixon fight for his political life. Nixon saw the red light go on. Internally unconvinced he could win, he began.

He was a man “of modest circumstances.” His father was a grocer, his mother a housewife raising five boys. They all worked at a family store. Mothers with sons in Korea and fathers who landed at Normandy listened to the candidate speak about his Navy service.

He detailed his expenses and debts, down to how much he still owed to his parents and his 1950 Oldsmobile. Pat did not have a mink coat. She had a “respectable Republican cloth coat.” “And I always tell her that she’d look good in anything,” he added.

"Well, what did you use the fund for, Senator? Why did you have to have it?" Nixon asked himself. There were a few ways to fund travel expenses, political broadcasts and printing, he said. One way was to be rich — but as he explained, he was not. Another was to put his wife on the payroll, which he couldn’t do, as it would take a job away from a deserving stenographer or secretary. He could not practice law, either. So, he could only have his contributors pay.

He admitted that the Nixon family did receive a gift after the election. Pat had said on the radio that their two daughters did not have a dog. One day, the Nixons received a message. They had a package waiting for them down in Union Station, sent by a man in Texas.

“It was a little cocker spaniel dog in a crate … Black and white spotted. And our little girl — Tricia, the 6-year-old — named it Checkers,” he said. “And you know the kids, like all kids, love the dog, and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we're going to keep it.”

Nixon said that whether he should stay on the ticket ought to be in the hands of the Republican National Committee. Evading Eisenhower’s orders, he asked the viewers to wire and write to the RNC.

The “Checkers” speech, as it came to be known, was a hit. Calls and telegrams from hundreds of thousands of viewers came rushing in. The RNC counted the thousands of wires they received from people with Republican cloth coats who worked in family stores. They were 350 to 1 in favor of Nixon. It was less than 2% of the viewership, but it was enough.

Not everyone approved of the speech. “We do not detect any desperate impoverishment in a man who has bought two homes, even if his Oldsmobile is two years old,” the New York Post read. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch called it a “carefully contrived soap opera.” When Nixon ran for president, hecklers asked him about his dog.

Who cared? Nixon stayed on the ticket. When Eisenhower met him at a West Virginia tarmac that day, the older man grinned, put his arm around him and said: “You’re my boy!”

But the agonizing ordeal had left Nixon thoroughly embittered. The old wounds from the Hiss trial split open and bled heavily. Already painfully shy and insecure, he felt that the newspapers were intent on “reveal[ing] him to be a poor and clumsy boy,” in the words of New York Herald Tribune reporter Earl Mazo.

He would not forgive. He could not forgive. Not when photographers set up empty bottles outside the hotels he stayed at so they could snap an incriminating photo when he walked out of the door. Not when headlines accused the Nixon family of living above their means when they didn’t even have air conditioning. Not when Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts angrily told an aide that Nixon “was a victim of the worst press that ever hit a politician in this country.” Those around him saw the vice presidential hopeful turn inwards and look at the rest of the world with suspicion.

From then on, Nixon adviser James Bassett said, “A serious young man became a political megalomaniac.”

Editor’s note: Much of the information for this article was sourced from John A. Farrell’s 2017 book “Richard Nixon: The Life” and Stephen E. Ambrose’s 1987 book “Nixon, Vol. 1: The Education of a Politician, 1913-1962.”

Audrey Wang is a Trinity senior and data editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume. She was previously editor-in-chief for Volume 119.