Duke Screen/Society’s screening of Sean Baker’s “Anora” (2024) was their best attended event of the semester by far. Ten minutes before the movie’s scheduled start, the Rubenstein Arts Center Film Theater was full, and by the time the screening began, there were students sitting on the floor, craning their necks to see the screen.

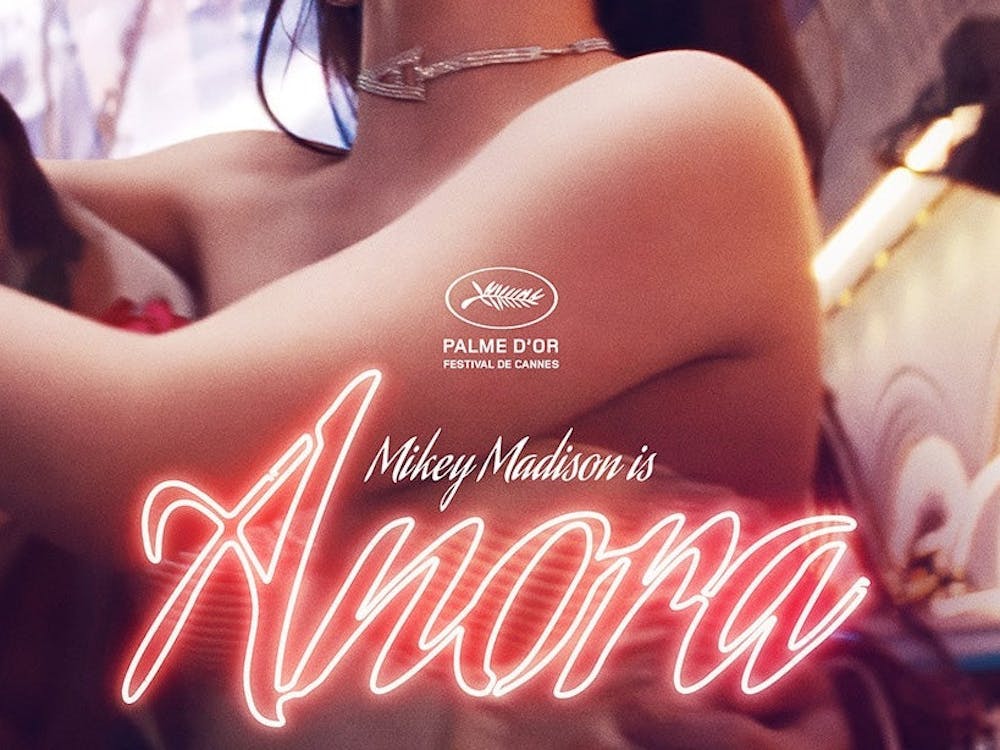

“Anora” is a 2 hour and 19 minute Palme D’Or winner that functions as a romantic comedy, but not in a light-hearted typical “rom com” way. “Anora” follows the titular character (Mikey Madison), a New York City sex worker who goes by Ani, as she falls in love with and marries the wealthy Ivan "Vanya" Zakharov (Mark Eydelshteyn). When Vanya’s parents find out, they send two men to force an annulment of the marriage, causing a number of intense action scenes.

Baker is known for creating films that focus on the lives of marginalized people, especially sex workers and immigrants, and “Anora” is no different. Earlier this year, he told Variety Magazine that he hopes to help “remove the stigma that’s been applied” to sex workers across the world. From early on in “Anora,” the audience can tell that Ani will be a significantly more developed character than the generic, stereotyped prostitutes found in other films. Shots of her are regularly from eye level, so the viewer sees her as an equal instead of looking down on her, and there are frequent close ups of her face and eyes, emphasizing emotions and further humanizing her.

One of the aspects of “Anora” that is so successful is the film’s appeal to the audience’s emotions. Baker perfectly captures the exhilaration of the honeymoon period in a relationship and then skillfully transitions out of it. When Ani and Vanya fall in love, the audience is swept along and feels joy, perhaps against their better judgement. As Vanya’s parents try to break up the relationship, the audience feels Ani’s Ani, who uses the labels of “husband” and “wife” as a crutch to lean on when their relationship is threatened. Personally, the film left me questioning the purpose and meaning of marriage and relationships as a whole, and whether society puts too much stock in empty labels.

Although the film, leaves the audience questioning serious issues like what makes a marriage successful and the stigmas around sex work, the comedic aspects are never far. The bickering dynamic of the Russian henchmen who attempt to get the marriage annulled is reminiscent of cartoon villains, with exaggerated and humorous reactions to each other. The inclusion of foolish henchmen in and of itself is not necessarily unique or witty, but the contrast between their ridiculousness and the genuineness of Ani’s fear and sadness is comedic.

“Anora” is marked by pairs in more ways than just the dual comedic and serious tones. There are stark differences between the vibrant and energetic night club scenes and the bright and airy daytime scenes. There is a striking moment where Ani removes her makeup for the first time halfway through the film, and she does not reapply it, creating almost a second version of herself for the audience. In terms of cinematography, there are moments where the camera is handheld, following Ani and making the viewer feel as though they are living her life and seeing through her eyes. There are also numerous still two-shots, where two characters are seen talking to each other and the audience is reminded of their position as an outsider in the scene. Even though the film incorporates a number of different styles and components, there is still a sense of homogeneity and cohesiveness throughout the work.

The screening of “Anora” at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year ended with a 7.5 minute standing ovation. The ending of Duke’s screening was the stark opposite - no one clapped. Instead, everyone sat still in silent contemplation. Both responses are a testament to Baker’s work; he created a deeply captivating and entertaining film that is simultaneously thought-provoking. Although the film ends with a somewhat cliché changing of seasons and first snowfall, the piece as a whole is unique and manages to perfectly balance complexity and somberness with engaging humor.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Sonya Lasser is a Trinity first-year and a staff writer for Recess.