In recent years, crises throughout the Middle East and North Africa have led to large-scale migration into Europe. This influx has sparked both concerns about straining limited government resources and unfounded nativistic fears of cultural replacement and marginalization. In response, European governments have instituted a number of strict anti-migration policies.

These policies have led to repeated tragedies in the Mediterranean, where migrants attempt risky voyages in unsafe vessels in hopes of reaching Europe. Many of these vessels sink, resulting in hundreds of deaths and disappearances each year. While statistics capture the scale of these losses, they often inadvertently obscure the human tragedies these policies produce. “A Maritime Haunting” sought to change this by relying, in part, on one of Europe’s most influential art forms: Greek theatre.

Greek theatre consists of three main genres: tragedy, comedy and the satyr play, a comedy-tragedy hybrid with a chorus of actors dressed as satyrs. Each is different in its focus and general themes, but all rely in large part on a chorus: a group of performers commenting on the events of the play, often speaking directly to the audience. “A Maritime Haunting” used this chorus structure as its foundation.

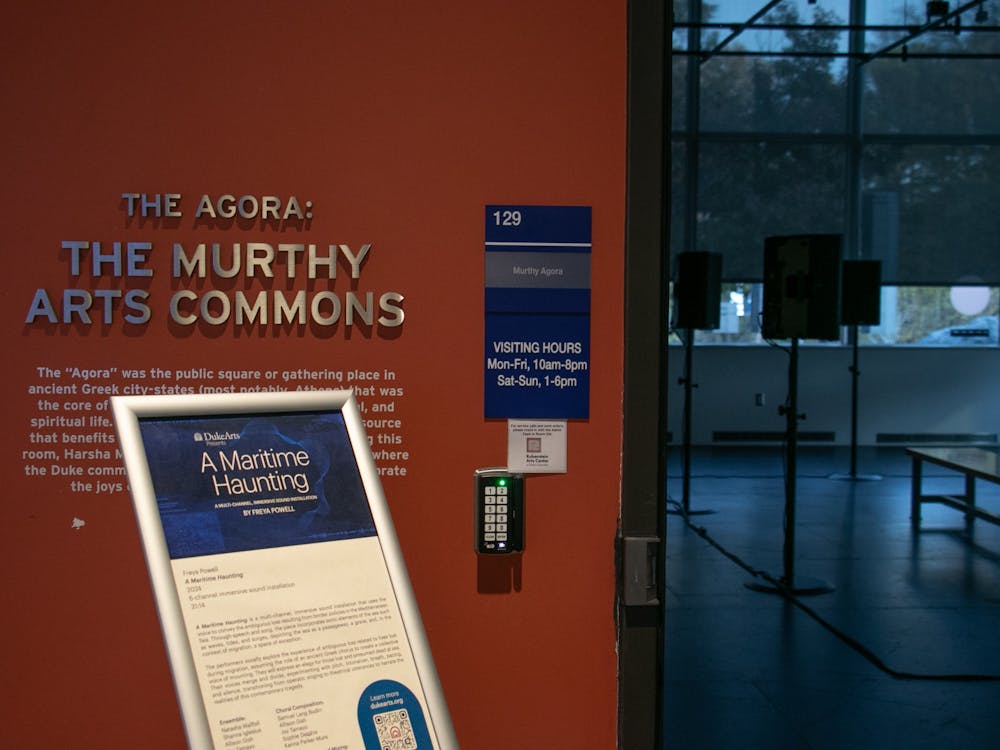

“A Maritime Haunting” was a multi-channel immersive sound installation transforming the Greek theatrical tradition into a meditation on the loss created by European border policies and an elegy to those who have perished. The installation was created by Freya Powell, a visiting artist and Professor at the New School’s Parsons School of Design, whose work spans ensemble performances, sound installations and video essays focused on loss, grief and the ties between individuals and the collective. Powell partnered with six singers, five composers and a sound designer to bring the piece to life.

The exhibit was housed in the Rubenstein Agora, a small room on the Ruby’s first floor. Upon entering, visitors saw a solitary wooden bench in the center of a mostly empty room, surrounded by six speakers. Each speaker played the voice of one singer; together, these voices formed a chorus whose message lasted about half an hour.

The chorus operated as both individuals and a collective. At times, one speaker played a message about what has happened in the Mediterranean and why. At other times, two or more played back and forth, not in a dialogue, but rather as a unified story. Often, the remaining speakers provided background ambiance, and at the end of almost every portion, the speakers sang in unison, expressing grief and sorrow.

The performance itself was almost indescribable, but the experience is incredibly beautiful and moving. The chorus singers, while presented through speakers, still managed to bring incredible emotion to their voices and songs. Yet while the sense of sorrow and loss was strong, the listener was not overwhelmed into numb acceptance.

The messages of the chorus varied. Listeners heard the stories of boats overloaded and unfit for sea, where migrants starve and suffer, often capsizing and dying. The seas they navigated were described as “weaponized,” patrolled by aerial vehicles and boats working to keep migrants out when possible, a weaponization and militarization of shared water rarely seen outside of wars. States embrace the exception of keeping out certain immigrants as the rule, and hundreds die in attempts to reach Europe.

The chorus also highlighted the minimization of migrant issues by society and the press. In June 2023, the Titan submersible imploded, prompting a week of full-time coverage. Just a few days earlier, the Adriana sank in the Mediterranean, resulting in the deaths of between 82 and 500 migrants. Despite the massive difference in loss of life, the tragedy of the Adriana was completely overshadowed by the Titan.

While varied, the messages all revolved around a central critique: that Europe’s current policy towards migrants emphasizes legality and fear over kindness and compassion. Even when European authorities encouraged domestic vessels to offer food and water to migrant vessels in need, it became clear that anyone who accepted aid would be returned to North Africa.

The performers repeatedly returned to the sea, talking about its color, scale, scope and power. Again and again, these traits are tied to death and suffering, transforming the Mediterranean from a body of water into a cemetery and memorial.

Overall, the exhibit was novel without distracting from its real and important message. It used the Greek chorus in a way that connected the immigrants' stories to Europe’s history without reducing their message to just another tragic tale. In an era of rising nativism, the message took on additional importance as a reminder that behind every decision and action are real human lives and stories.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Zev van Zanten is a Trinity junior and recess editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.