As winter sports are underway, The Chronicle is back with our breakdown of every sport, including key rules, terminology, tournament formats and more. Here is swim and dive:

Overview

A college swim meet consists of 16 to 21 different events, in which swimmers race to score points for the fastest finishes. Men and women compete separately, with the women’s heat of any given event occurring right before the men’s. Depending on the meet schedule and caliber, competition can last anywhere from four hours to four days.

Collegiate races occur in a 25-yard long pool. Typical race distances include 50 yards (two laps), 100 yards (four laps), 200 yards (eight laps), 400 yards (16 laps), 500 yards (20 laps), 1000 yards (40 laps) and 1650 yards (66 laps, often referred to as “the mile”). Swimmers tend to specialize in either sprint or distance events, as well as one of the four different strokes.

Collegiate divers compete in up to two events at every meet: the 1-meter dive and the 3-meter dive. Both are performed from a springboard, and athletes earn points for the execution and difficulty of their dives. Some diving invitationals, as well as NCAA Championships, include a platform dive event in which divers flip off a stationary, 10-meter-high surface.

Terminology

Butterfly: A stroke that pairs dolphin kicking (both feet together) with a simultaneous open-water recovery of both arms. Often referred to as “fly,” this style of swimming is powerful but extremely taxing.

Backstroke: Swimmers perform this stroke on their backs using flutter kicks and alternating arm movements. Backstroke races begin from the water rather than the blocks, and athletes must remain on their backs for the entire race.

Breaststroke: This stroke employs a frog-like kick, circular arm movements and a specific underwater pullout. Unlike other strokes, swimmers must breathe with every cycle. Breaststroke requires great coordination and powerful kicks and pulls, but it is the slowest of the four strokes.

Freestyle: Though athletes are technically free to swim any stroke they wish in freestyle events, the fastest option is swum face-down with an alternating arm pattern and flutter kicks. This is the most versatile stroke, and it is also the only one to be raced for distances longer than 200 yards.

Individual Medley (IM): The IM allows swimmers to compete all four strokes in a single race. A 200-yard IM entails 50 yards of each, while a 400-yard IM requires 100 apiece. Athletes swim butterfly first, followed by backstroke, breaststroke and freestyle.

Turns: Swimmers employ turns whenever they encounter walls mid-race. Flipturns (performed in the freestyle and backstroke events) look like an underwater somersault. Open turns (performed in butterfly and breaststroke events) require a two hand touch and involve the head exiting the water. Crossover turns (used only to transition from backstroke to breaststroke in an IM) resemble a sideways flip-turn but must begin on a swimmer’s back.

Relays: Four swimmers participate on any given relay team, and each athlete swims a quarter of the relay distance. For example, a 200-yard relay involves four 50-yard legs. Athletes swim one at a time under a running clock, with the next leg of the relay diving from the blocks as soon as his or her teammate touches the wall. The first swimmer on a relay is called the lead-off, and the final swimmer is called the anchor. In medley relays, each leg swims one of the four strokes (in the order backstroke, breaststroke, butterfly, freestyle).

Heats: Most collegiate pools have only eight lanes, so when more than eight swimmers enter an event, they swim in “heats” of competition. These groups are organized by seed time (see below), and heats are swum from slowest to fastest — with the exception of distance events, which are swum fastest to slowest.

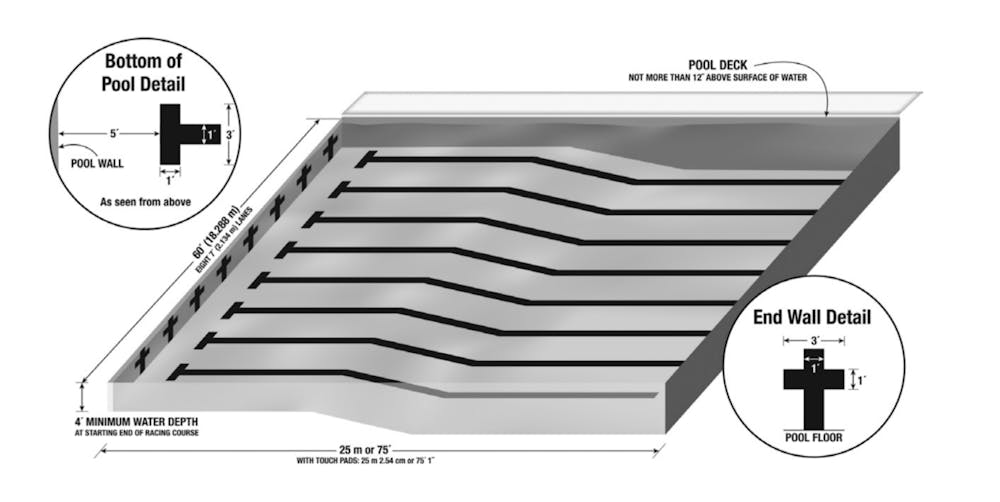

Blocks & touchpads: The apparatus that a swimmer dives off of to begin the race is called a block. Touchpads, which line the underwater wall directly beneath the blocks, are part of a larger computer system used to register a swimmer’s splits and final times as accurately as possible.

Splits: Since athletes make contact with the touchpad every 50 yards, the pool’s timing system keeps a record of their times throughout the race. These are called splits, and swimmers find them helpful for training and race planning purposes.

Seed time: The time a swimmer uses to enter a meet is called a seed time. This information is typically available on the heat sheet, and it helps to organize the athletes into the proper heats so that they race swimmers of a similar speed.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Standards/cuts: Some competitive invitationals, including NCAA Championships, require swimmers to qualify with a certain time. This kind of requirement is known as a standard or cut.

Think of it as a “ceiling” for entry — the swimmer must prove at another meet, often during the same season, that he or she can successfully complete the event under a certain amount of time.

-Abby DiSalvo

Scoring

The team that receives the most points over the course of a meet is declared the winner. Swimmers and divers earn points for their team based on how well they place in their events. (See “season format” for more on the difference between dual meets and invitationals.)

Dual-meet scoring: In individual dual meet races, a 9-4-3-2-1-0 points pattern is used (the first-place swimmer receives nine points, the second receives four, and so on). Only the top three finishers from each team can score points. For relays, scoring transitions to an 11-4-2-0 pattern. Only the top two relays from each team may score, and the extra point imbalance makes relay strategy crucial.

Invitational/championship scoring: At larger meets, swimmers compete against more opponents and therefore receive more opportunities to score points. The typical pattern awards the top sixteen individual finishers (in a 20-17-16-15-14-13-12-11-9-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 pattern) and top sixteen relays (40-34-32-30-28-26-24-22-18-14-12-10-8-6-4-2). Note that relays are worth double that of individual events, making them extremely competitive.

Most competitive invitationals and championships operate on a trials-finals basis, where swimmers must swim their event twice. In “prelims” (also known as trials), large numbers of swimmers compete to qualify for a more selective final race. The top sixteen qualify to return.

The fastest eight of these swimmers seed into the A final, while the remaining eight compete in the B (or consolation) final. Original places become irrelevant. The swimmers repeat the event, typically later that night, and points are awarded as described above. However, swimmers in the B final cannot place higher than ninth place, even if they outperform a swimmer in the A final. Likewise, swimmers in the A final are guaranteed at least an eighth-place finish.

Dive scoring: Diving points are a bit more complicated. For each individual dive, judges provide an execution-based score ranging from 0 (completely failed) to 10 (perfect). At meets with two or three judges present, these scores are added up. At meets with five judges, the lowest and highest scores are canceled, and the median three are combined. This number becomes the dive’s execution total, which is multiplied by the degree of difficulty (sometimes known as the tariff) to provide a total score. The process repeats itself for each dive.

An athlete’s final diving score is calculated by the sum of their individual dive scores. In the case that only two judges are present, the final score is multiplied by 1.5. As in swimming, placement by divers contributes points to the team’s overall total.

Penalties

Officials at each collegiate meet observe swimmers to ensure that they perform each stroke correctly. For those who are not following the rules of each stroke, the officials will give out a disqualification card — known as a DQ slip — to the swimmer. This invalidates any points received for their race and ensures their time does not count. The DQ slip will state the rule that the swimmer violated. There are different types of infractions for each stroke that may cause a swimmer to receive a disqualification.

The most basic rules of a race, specifically in freestyle, are that a swimmer may not pull on the lane line, touch the bottom of the pool, or fail to touch the wall in multiple-lap races. In any race, swimmers may not remain underwater for more than 15 yards off the wall.

Unique to backstroke, swimmers must remain on their backs at all times. If a swimmer turns more than 90 degrees, they are considered to be on their stomach and thus will receive a disqualification. In order to do a turn at the wall in backstroke, a swimmer may turn on their stomach and take a single stroke into their flip at the wall. Officials only count a turn done in a continuous motion, without stopping at the wall, as a successful backstroke turn.

Breaststroke has the most possible infractions compared to other strokes. The most widely known rule is that a swimmer’s hands must touch the wall simultaneously and at the same level at each turn or finish. While swimming, an athlete cannot remain underwater for two or more strokes throughout the length of the race. The order of the breastroke movement also requires exactly one arm pull followed by one leg kick. In a normal stroke cycle, a swimmer's hand cannot pull past their hips (besides in the pullout, at the start of each lap). After pushing off the wall, a swimmer is permitted to do one stroke past their hips, one butterfly kick, and one breaststroke kick all under water. Any violations of these rules will result in a DQ.

The infraction that exists for butterfly is similar to breaststroke in the case that a swimmer’s hands must touch the wall at the same time, but they do not need to be at the same level. The most important rule in butterfly is that a swimmer's legs and feet must kick simultaneously and together. The arm recovery of the stroke must also occur above the water.

-Ava Guglielmo

Additional rules

False start: A false start is declared when the swimmer moves or leaves their starting position before the starting signal. Officials will issue a DQ slip to the offending athlete.

Relay starts: Any swimmer on the block is only permitted to start their leg of the race when the previous swimmer’s body touches the wall. In other words, the next swimmer’s body still needs to be touching the block when the current swimmer finishes and touches the wall.

Pool flags: Flags are strategically placed five meters from each wall. The designed placement is to help backstroke swimmers understand their distance from the wall in order to efficiently turn. Athletes know their “stroke count” — the number of arm cycles it takes to swim from the flags to the wall at full speed — which allows them to flip over at the proper distance and perform a turn without hitting the wall.

Technical suit policy: One-piece suits that extend to the knee are called technical suits (more commonly known as “tech suits,” “kneeskins,” or “fastskins”). Thanks to specific seam placement and hydrophobic material, these suits are scientifically proven to help swimmers race faster. As a result, they are common to see at invitationals or competitive dual meets. Though not relevant to college competition, USA Swimming recently prohibited swimmers under the age of 12 from wearing technical suits.

-Kate Reiniche

Season format

By the end of this season, the Blue Devils will have competed in 15 dual meets and invitationals against numerous teams in the NCAA. Four of those dual meets involve ACC opponents, though Duke has already finished competing against Virginia Tech.

A dual meet is a swim meet in which two teams compete against each other in about 16 events per men’s and women’s teams. The duration of a dual meet can vary. Sometimes, it spans from two to four hours in one day. In other instances, it extends across two days with events split in half for each day and breaks between every few events.

Beyond dual meets, the Blue Devils will also compete in invitationals, which include a wide variety of teams and typically extend from two to four days. At these meets, the competition pool decreases each day due to preliminary and final rounds that occur in the morning and evening, respectively. Invitationals also require certain cut-off times for swimmers and relay teams in order to qualify to compete in the meet.

The ACC and NCAA Championships will conclude Duke’s season and are also invitational meets.

Coaching staff and recent trends

Head coach Brian Barnes, entering his second year with the Blue Devils, is looking to build off a successful 2023-24 women’s season. The former N.C. State associate head coach will also work to translate his successes with the Wolfpack to the Blue Devil men.

With only one year under his belt, Barnes has already led Duke’s team to the ACC Championships, where the men placed tenth and the women placed fifth. He also helped the women’s team to the 2024 NCAA Championships, collecting another program-high placement. Overall, Duke’s women’s team has historically been more successful than the men’s, and they look to continue this trend with returning stars Kaelyn Gridley, Ali Pfaff, Tatum Wall and Aleyna Ozkan already commanding both relays and individual events. Diver Margo O’Meara, returning for her senior season, is also a powerhouse on which to keep an eye.

-Tyler Rogers

Click here for The Chronicle's beginner's guide to every sport.

Abby DiSalvo is a Trinity sophomore and assistant Blue Zone editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.