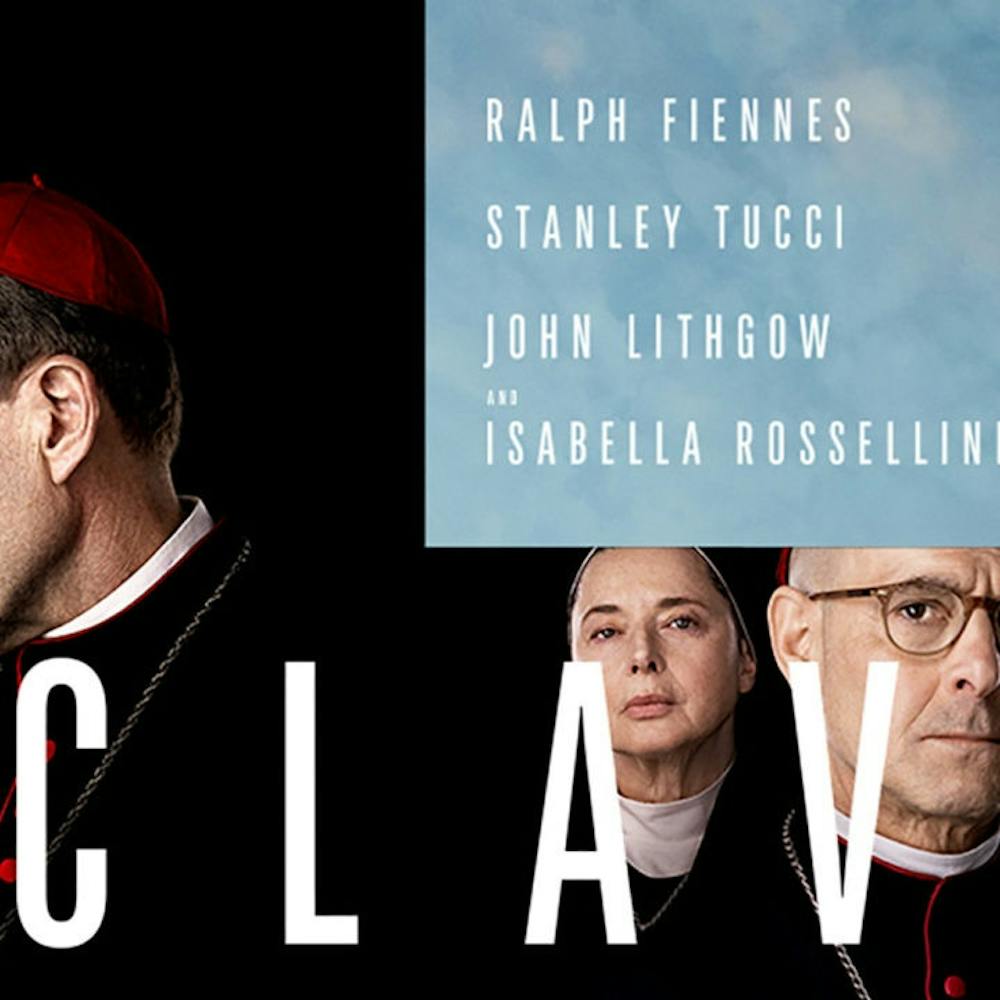

The Pope has died, and four prominent figures in the Church adorn his bedside, their faces somber and their minds churning. “Conclave,” directed by David Berger, director of “All Quiet on the Western Front,” follows Thomas Cardinal Lawrence (Ralph Fiennes) who is tasked with overseeing one of the most prominent traditions of the Church — the selection of the next Pope. The film is based on the 2016 Robert Harris novel of the same name.

“Conclave” finds itself in physical and intellectual spaces that its thematic and argumentative self could never hope to fill. It is in the lineage of mystery/thriller films where opinionated people talk in rooms — films like “12 Angry Men,” “Spotlight,” “Glengarry Glen Ross” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”. Sadly, it can not remove itself from their shadow.

In the film, there are four realistic options for the papacy, each with their ideological and personal questions that the plot is all too eager to reveal in sequence and with flair. It is this tangibility of the plot that limits the promise of the concept of “Conclave.” What would initially appear as a high brow, well-acted chamber drama becomes pulpy and melodramatic. There are lunchroom dramatics, cordial confrontations and righteous defiances from the forgotten.

Watching this film is like riding along in a car composed solely of an engine. While the usual, well crafted car would have things like a quality transmission, drive shaft, seating and steering, this car is in love with the motion and fervor of its pistons and offers the rider nothing else.

What I mean by this is that every character functions to serve the machinations and orchestration of the plot — outlined by both the original author and the screenwriter. One can almost picture one of them sitting in their living room or in a coffee shop writing a certain twist or reveal before leaning back in their chair pleased with themself.

This type and level of script was able to draw in big names alongside Fiennes: Stanley Tucci, Isabella Rosellini and John Lithgow. They are all wildly adept at giving their fleshy plot devices nuance and depth, but there is only so far to go when the goal of the movie is to induce “oohs, “ohs” and “woahs” from the audience. Like a TV show jumping the shark, the turns and choices continuously escalate and progressively strain credulity. This ends in a final “twist” that is both thematically vapid and narratively dumbfounding. With the plot so goaded-over, the hardest decision of the film appears to be deciding where all of these secretive conversations could occur without getting locationally repetitive and stale.

To drive a plot, a movie needs conflict. “Conclave” is willing and able to provide. The text’s thesis is that the Church must embrace everything in the face of a changing world — a noble argumentative pursuit that is rendered moot by the lack of spiritual fortitude in the film. The “villains,” the conservative, regressive Cardinals that stand in the way of Fiennes’ march toward a new Church, are given minimal nuance or personal agency. They are strictly a road block. Stanley Tucci’s character joins Fiennes in his battle, with this he is rewarded with screen time and internal vacillations. Intrapersonal conflict within the conclave proves to be the only true virtue. With the ideological conflict of the film and the timing of its release coinciding with the current American political climate, the veil of allegory is exceedingly thin.

While the allegory is apt and most likely reflected within the actual walls of the Vatican, this same aptitude is what proves the frivolity of the framing of the film. To get people to see a film they have both knowingly and unknowingly experienced before, Berger uses a location of mystery and intrigue. Not to serve any real purpose, but to provide the aesthetic of a dense, weighty film. The film is at its best when Fiennes is an arbiter and manager. His crisis of faith is mentioned, but it offers no real context to his character. The film has already beaten you with the idea that conflict is virtue; they do not need the backdrop of Catholicism to embolden this point.

As gleaned at prior, the film’s obsession with itself implodes with the final twist — an unearned Christ figure and “Get Out”-style condemnation of liberal identity politics converge into a hopeful yet annoying conclusion. Through its half-effort subversion and mechanical feel, “Conclave” shows its dislike of its audience. It knows what you want and will tease you with it, while staying more concerned with its personal goals. It is the type of film that is aimed at your mom and dad, yet it treats them as innocently naive and artistically unquestioning. It will probably be up for best picture.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Kadin Purath is a Trinity junior and a culture editor for Recess.