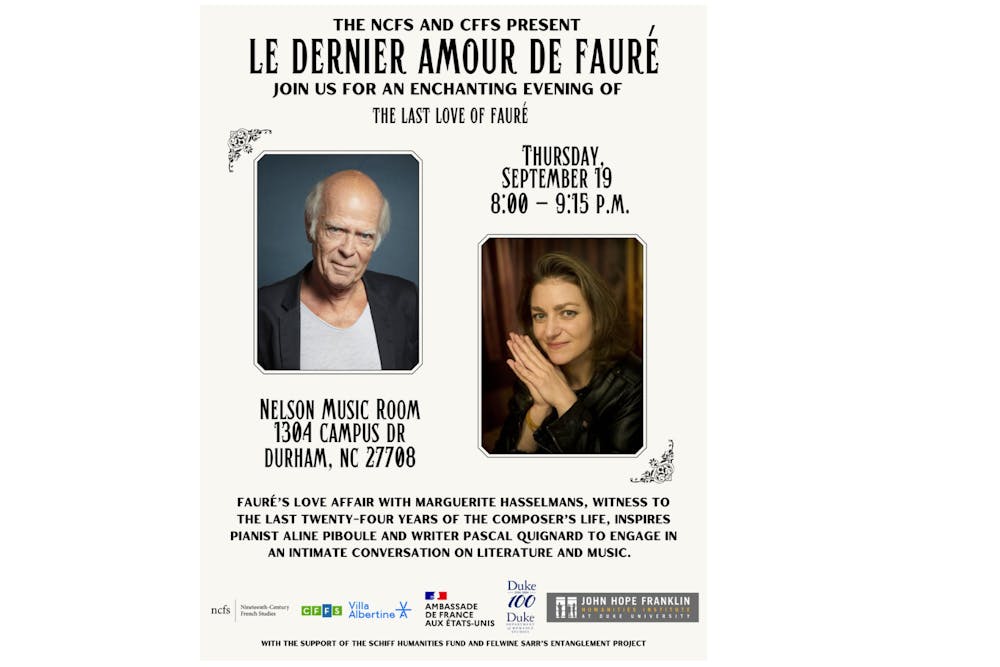

Writer Pascal Quignard and pianist Aline Piboule walk on stage hand in hand, wearing black pants and a long sleeve shirt and black pants and a silver sequin jacket-top combo respectively. They lock hands center stage and bow, afterwards retreating to their respective seats. Quignard opens his mouth to speak into a microphone but a train whistles; the crowd laughs.

“Le Dernier Amour de Fauré,” Quignard says, in a suitably deep voice, once the train has passed by. It’s roughly 8:07 p.m. in the echoey Nelson Music Room on a cool Thursday night in September. He nods to Piboule and she begins to play.

The rest of the performance was similarly characterized by an intimate simplicity. After each piece, there was no ostentation or unnecessary explanation of the content; Quignard would seamlessly begin to read a section of his prepared text. This pattern continued, ending with “Nocturne no. 13.” It was just a piano and a chair, a man and a woman, a piece and a passage.

The event emphasized intermedial study and the cooperation of music and literature, yet also the sovereignty of each medium. In the Q&A portion, Felwine Sarr, Anne-Marie Bryan distinguished professor of French and Francophone studies, asked Quignard about the purpose of his prose in relation to the music. Quignard said that the writing is not there to explain the music, but rather it functions as a compliment in this performance. The music does not need the text and the text does not need the music. However, they are wonderful together and communicate profound depth when paired.

The opening composition, “Improvisation,” an extract from “Huit pièces brèves,” was deftly played by Piboule — the pauses having just as much weight as the notes themselves. While writing this review, I created a playlist of the same pieces in the same order as a refresher, but none of them were played by Piboule. The contrast revealed just how uniquely skilled she is at embodying Fauré's music.

There is an ineffable quality to how she plays. Even for more chaotic and challenging works like “Nocturne no. 13,” the pianist commanded the notes in a way that felt innate rather than learned.

As the final note from “Improvisation” rang out, Piboule let it linger. Its leaden circles spread through the air, collecting each audience member one by one to create a united consciousness, disconnected from individual ego.

“There also are moments in music where I am in a world for which there are no words ... the music takes me completely,” Piboule said in French, with translation by actress Amanda Gann.

Once the note had completely ended, Quignard cleared his throat and began to read the first section of his prose.

His passages were deeply profound, and the writer humanized Fauré, while philosophizing through him. The text was both bitterly bleak and romantically nostalgic, matching the desolation of “Nocturne no. 11” or the reminiscence of “Barcarolle no. 13.”

Quignard’s familiarity with the tortured artist — his award winning novel “A Terrace in Rome” being about love causing the disfigurement and madness of an engraver — lends itself to an adept communication of the composer’s musical and psychological evolution.

The selected music advanced in rough chronological order, so the audience could hear how Fauré’s music became increasingly chaotic and atonal, losing the chronos of his earlier works. This musical trend was supported by the complex psychological insight of the prose, as Quignard detailed how the composer became increasingly deaf and increasingly in love with Marguerite Hasselmans.

The text begins and ends with Hasselmans, Fauré’s last love, so her importance in his last years was a significant focus of the event.

“I need you in order to live,” wrote Fauré in a letter he sent to Hasselmans that was quoted by Quignard.

This need is dual in nature: Fauré needed her feedback on his music when he could no longer hear, and he needed her emotional and intellectual companionship.

Once the performance ended and the first brave soul began to clap, the applause lasted three minutes and contained seven bows.

Despite Piboule and Quignard having collaborated before, the program maintained its novelty. Their collaboration was well coordinated but not routine, and I felt their genuine passion for Gabriel Fauré.

The questions by faculty to Quignard and Piboule carried nuance and philosophical weight as well as logistic clarity. However, it felt unbalanced compared to the performance's much more dominant weight; the conversation would have benefitted from greater length. I was left wanting more.

Regardless, the content of the discussion was a good insight into Piboule and Quignard’s partnership and methodology, as well as their personal beliefs on Fauré.

As the audience began to trickle out, some stayed behind in hopes of shaking hands with Quignard and Piboule. The academics lingered to socialize with their colleagues. Amongst them all, I could hear whispers of praise and an acknowledgement that they had been party to something special.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.