It is no secret that, for most of recorded history, women were almost entirely shut out of the world of science. While some managed to participate in science by hiding their identities or through special circumstances, countless talented women were denied the chance to exercise their agency. However, there was one way that many women were still able to be involved in science: document illustration.

“The Scientific Vision of Women,” a Duke Libraries exhibit that was first installed in the Mary Duke Biddle Room Aug. 14, 2024 and which will remain there until Feb. 15, 2025, seeks to shed light on this often neglected sector of women in STEM. The exhibit was curated by Meg Brown, Brooke Guthrie and Lauren Reno with contributions from numerous members of the Duke community. It draws from various archives at Duke and beyond to tell a story that spans centuries and continents.

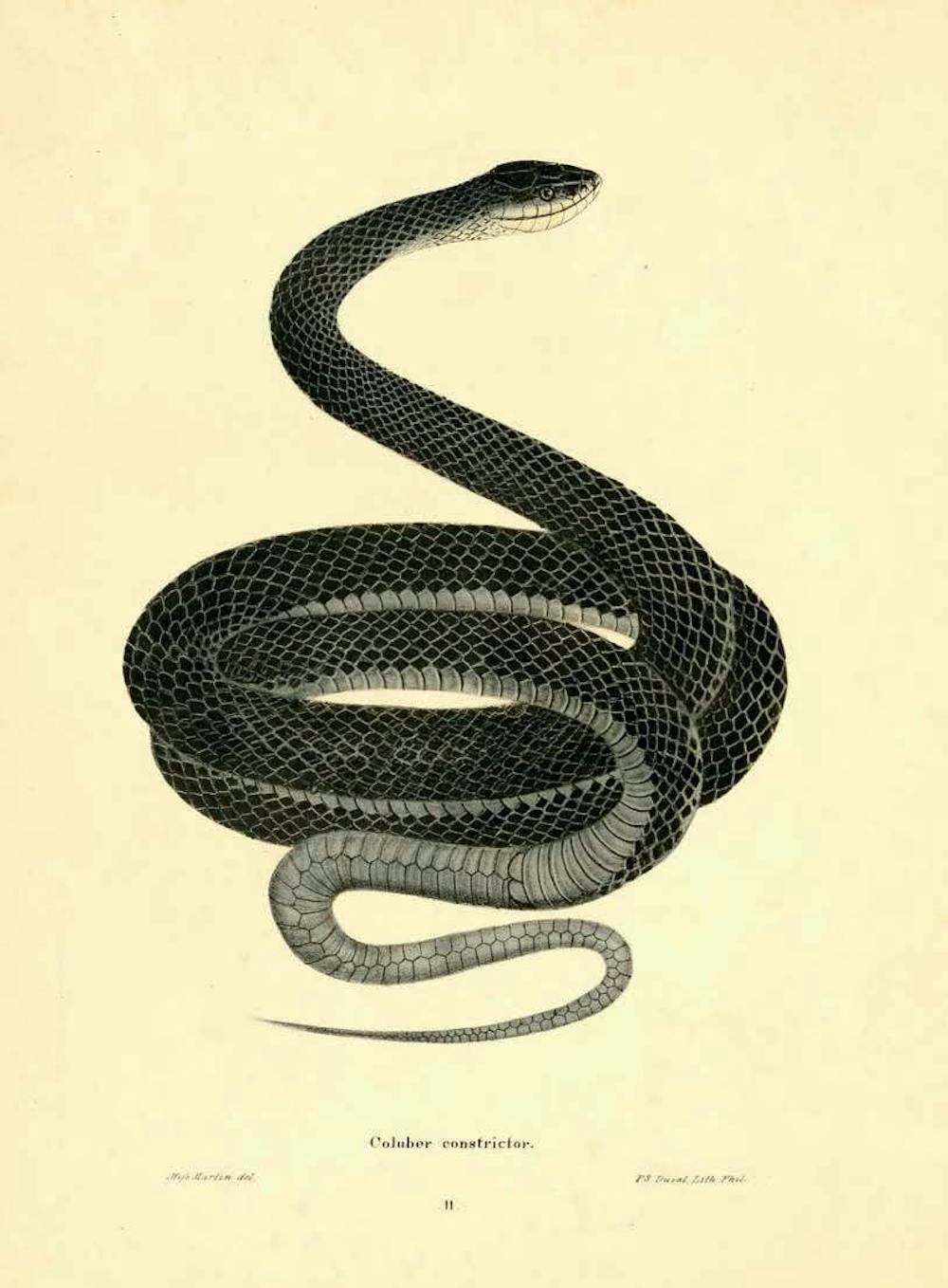

Throughout human history, scientific illustration has played a key role in helping people communicate and comprehend difficult concepts. It has also been essential in overcoming language and literacy barriers so that scientific ideas could cross borders and class divisions. And since the beginning , much of this work was done by women, who spent hundreds of hours making accurate and detailed drawings of everything from machines to plants to minerals.

The exhibit displays 21 stories from across eras and disciplines. The women themselves have differing levels and styles of involvement. Some primarily did illustrations, while some were productive and important scientists who happened to also illustrate. Some were married to famous scientists, while others were employed by them. Some did all of their illustrations in their homes and were relatively unknown, while others were able to travel and be recognized for their contributions. A common thread linking them is the fact that they mostly lived in times where illustration was one of the few ways for women to contribute to science.

The exhibit also highlights two women currently working in illustration, highlighting the continued relevance of these stories. Jane Richardson, a James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Professor of Biochemistry, is behind the detailed ribbon-like drawings of protein structures that have inspired and educated generations of people working in the life sciences. Hillary Wilson, a Durham-based medical illustrator, works to describe the world around her and empower others through more accurate drawings.

The exhibit currently installed is not the original version, according to remarks given by Meg Brown at a reception discussing the exhibit. Out of a commitment to ensuring diverse, accurate representations of history, the original assemblers of the exhibit audited what they had found and realized they were not capturing the true scope of this story, as most of the people they were featuring were white Europeans and Americans. By consulting a wider, more diverse group of people and diving deeper into the archives, they were able to include perspectives from more continents and more backgrounds, and note how slavery and intersecting matrices of privilege and oppression have impacted many of the works showcased in the exhibit.

At the same panel, I had the privilege of hearing a number of curators and contributors give remarks on the illustrators who most resonated with them. It was a beautiful reminder of the ways in which we can relate to people who lived far before us, despite our differences. Colette Harley, an exhibit contributor and the Sallie Bingham Center Public Services Intern, focused on her own passion for botany and gardening and how this was shared by Jane Loudon, whose illustrations beautifully merged scientific detail with color. Alex Glass, a senior lecturer in Earth and Climate Sciences, talked about his wife being assumed to be an assistant despite her veterinary medicine degree, similar to how many of the contributions made by these women illustrated were ignored or assumed to be the work of men.

Overall, the exhibit highlights the strong historic link between science and arts, though perhaps not the type of link that STEAM seeks to create. It also evokes introspection into the long-time exclusion of women from science, which made me think about the real consequences of that exclusion. For example, if we had more women in life sciences, would we have avoided the problems created by a history of testing drugs primarily on men. Lastly, it gives the viewers a chance to think about how science isn’t just lab experiments and papers, but rather the product of all sorts of work and contributions, much of which is under-recognized or outright ignored.

If you’re curious about the history of science, love beautiful art, or just want to see something new, I’d recommend you check out this exhibit. You’ll be able to learn a lot about the progress our society has made and the progress we still need to keep making.

“The Scientific Vision of Women” can be found at the entrance to Perkins Library in the Mary Duke Biddle Room and will remain there until Feb. 15th, 2025. For those unable to view the exhibit in person, an online version can be found here. Additional details on the exhibit can be found here.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Zev van Zanten is a Trinity junior and recess editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.