In honor of Duke’s Centennial, The Chronicle is highlighting pivotal figures and events throughout the University’s history. Here, we take a look at Duke’s presidents:

From long before its founding in 1924, Duke’s administrative policies and sense of collective identity have been powerfully shaped by the vision of its many leaders.

To commemorate the University’s hundred-year milestone, The Chronicle is looking back on Duke’s presidents — each of whom guided the Blue Devil community through times of crisis and celebration, charting a distinct course toward the internationally acclaimed institution that stands today.

In the first installment, we review the five presidents who established Duke’s predecessor institutions and saw the school through the challenges of civil war and enduring financial hardship.

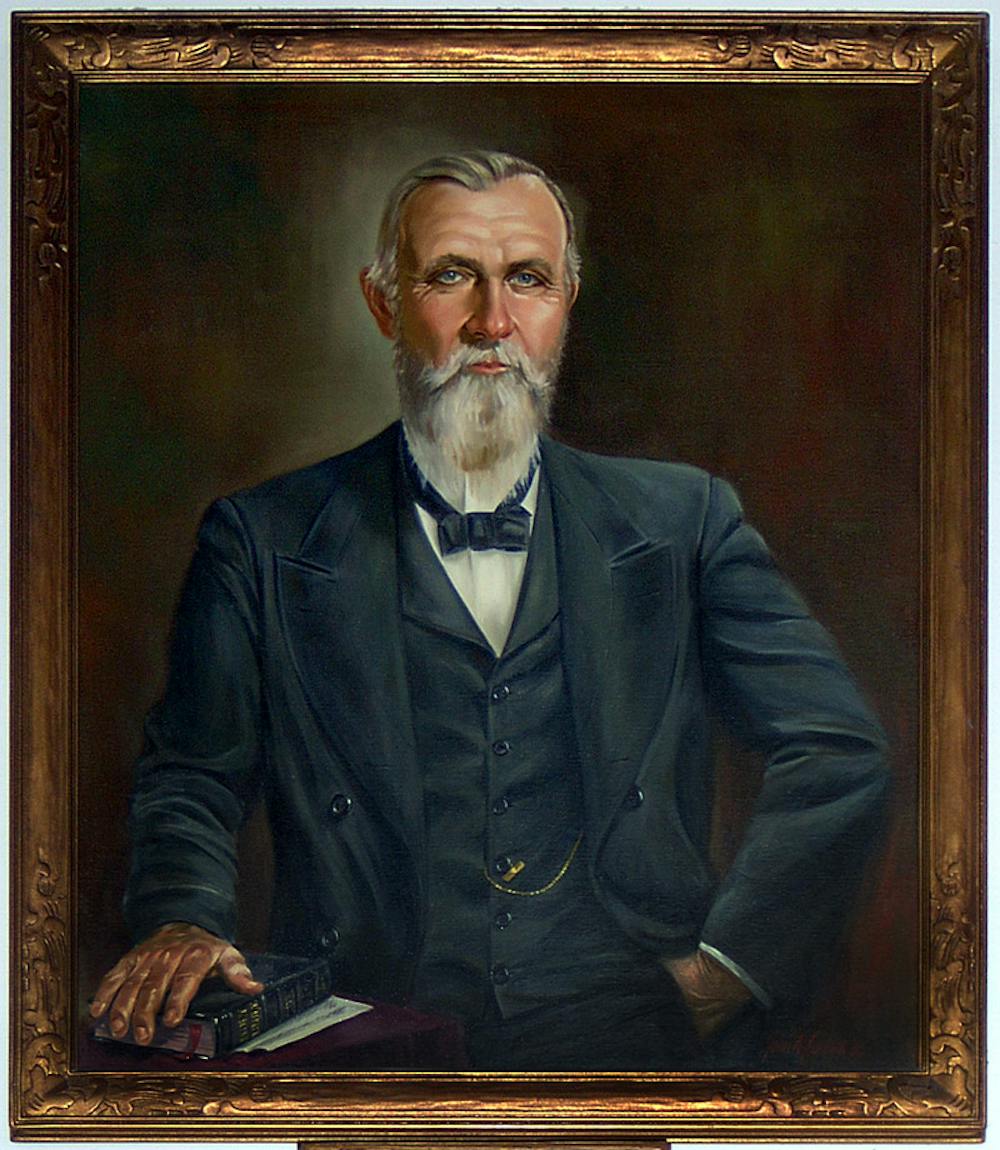

Brantley York, 1838-1842

Duke’s first “president,” York was a self-taught Methodist minister from Randolph County, N.C. Brought up during the Protestant revival period known as the Second Great Awakening, he attended a “camp meeting” in 1824 that inspired a lifelong personal religiosity.

The same year, a literary society formed at York’s local church. He joined and quickly found that his “thirst for knowledge led [him] to read too much,” an early indicator of his future career in education. York began preaching at Bethlehem Church in 1832 and later held teaching positions at a number of nearby schools.

In March 1838, York founded Brown’s Schoolhouse, a private subscription school in Randolph County. The one-room log cabin that originally housed only a handful of students would eventually grow into the sprawling University now located in Durham.

In his autobiography, York described the school’s first location as “a very inferior building” that was “entirely too small to accommodate the students.” As a result, residents of the surrounding area constructed a new building less than a mile away, and Brown’s Schoolhouse relocated in August with a class of 69 students to the site that would one day become Trinity College.

The next year, local residents convened again to create an “Educational Association” that would guide the school’s operations. The Union Institute Educational Society was formed in 1839, its name a reflection of the collaboration between the two communities it served: the Methodist-majority Hopewell and the Quaker-majority Springfield.

York served as principal of the school until 1842, when he was elected principal of the nearby Clemmonsville High School.

“The work of the four years spent at Union Institute was truly onerous, my faculties, both mental and physical, having been taxed to their utmost capacity,” York wrote in his autobiography.

Reflecting on his decision to leave the Union Institute, York noted that he was responsible for overseeing the school’s daily business and educational operations as principal, as well as for collecting funds to sustain the enterprise in his role as agent. As a result, he began to suffer from loss of eyesight, which left him nearly blind at the time of writing his autobiography.

York taught at various institutions in the years following his time at the Union Institute, founding five other schools before his death Oct. 7, 1891.

Braxton Craven, 1842-1863 and 1865-1882

As a child, Craven worked in the house of Nathan Cox, a Quaker who took Craven in after his father abandoned the family and his mother died of what was presumed to be tuberculosis. Biographer Jerome Dowd described Craven as an enterprising boy who “never shirked work.”

At age 15, Craven left the Cox household, resolved to “become his own master.” He decided to pursue teaching as a profession, first instructing a group of 25 to 30 students at just 16 years old.

At age 19, Craven joined the Union Institute staff as a teaching assistant in 1841. When York announced his intention to leave the school soon after, Craven planned to join him at Clemmonsville High. However, no other candidate materialized for the soon-to-be-vacant principal position, so Craven was elected to the role in 1842.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“Though I was anxious for him to go with me, yet such were his studious habits and his ability to learn, that I willingly recommended him as a suitable person for that position,” York wrote of his endorsement of Craven for the position.

Craven saw the school through two recharterings, first in 1851 as “Normal College,” then again in 1859 as “Trinity College.” The institution was supported both times by the North Carolina Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, which supplied funds for the first rechartering and formally acquired the college with the second.

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 threw Craven’s term into chaos. In December of that year, the slave owner and Confederacy supporter was tasked by the governor with overseeing a prison for Union soldiers in Salisbury, N.C. Craven held the position for about a month before being relieved, still retaining his presidency. He later relocated to Raleigh to become pastor of the local Methodist church.

The war quickly crippled Trinity’s operations, causing a reduction in class sizes and available resources. Facing intense criticism, Craven resigned the presidency in November 1863, feeling that “his teaching career was at an end.”

W.T. Gannaway, previously a professor at the college, served as president pro tempore in Craven’s absence beginning in February 1864. However, the same financial problems continued to plague Trinity, forcing its closure in April 1865.

Following the war’s conclusion, Craven was unanimously re-elected president in October 1865 after resolving the school’s outstanding debts.

Trinity College reopened in January 1866 with around 40 students. Craven used his personal funds to restock the school’s books and furniture, much of which had been stolen during the war.

Craven led Trinity until his death Nov. 7, 1882, having served as president for 40 years.

Marquis Wood, 1883-1884

Wood was born in 1829 in Randolph County as the tenth of 14 children. Reared on a farm, Wood enjoyed “very few advantages in early life” and joined the Methodist Episcopal Church at age 13.

In September 1850, Wood enrolled at the Union Institute. He received his preacher’s license in 1853 and graduated with “first honors” from what had since been renamed the Normal College two years later.

Wood worked for many years as a pastor in North Carolina and a missionary in China before returning to then-Trinity College to assume the presidency as the school’s first alumni leader. He was elected to the position in June 1883, following Craven’s death.

According to a biographer’s analysis of his personal diary, Wood “found that all the details as well as all the executive affairs and part of the teaching depended on him” as president. Trinity was still in a precarious financial situation, and Wood struggled to balance his responsibilities as an educator, traveling preacher and executive of the college during his term.

In Craven’s final year as president, he had enrolled 20 students of the eastern band of the Cherokee nation at an “Industrial Indian Boarding School.” The former president created the school at Trinity for the purpose of westernizing Indigenous students, forcing them to stop speaking their native language as part of the assimilation process.

After his death in 1882, the Board initially “refused to assume any responsibility” for the Cherokee students but allowed them to remain through the academic year, charging Craven’s son, J.L. Craven, with their “care and training.”

Wood brought the Cherokee students under the college’s jurisdiction in October 1883, and they were taught separately from Trinity’s other students. The policy change was reportedly financially motivated, as the government paid “$167 annually ‘for housing, clothing, boarding and teaching’ each of the Cherokees.” Wood noted in a June 1884 report to the Board that the college had earned $212.75 from keeping the students.

However, government funding for the Cherokee students was not enough to keep Trinity afloat. In June 1884, Wood offered his resignation. However, the Board of Trustees refused to accept the offer, and Wood continued to serve “reluctantly” as Trinity’s president.

At the Nov. 26, 1884, Board of Trustees meeting, a “Committee of Management” was formed consisting of Board President J.W. Alspaugh, Board Treasurer Julian Carr and James Gray. Wood then successfully resigned, and the committee was tasked with leading the college for the next two years.

After Wood’s resignation, the Cherokee students were returned to the supervision of J.L. Craven at a “specially organized ‘Cherokee Industrial School.’” In 1885, then-chairman of the faculty John Heitman — who “had always questioned the wisdom of retaining the Cherokees” — moved to abandon the school.

Wood died in 1893 and was remembered as “an ardent friend of education.”

John Crowell, 1887-1894

Born in Pennsylvania in 1857, Crowell served as principal of Schuylkill Seminary before joining Trinity College’s administration. He was elected president by the Board of Trustees in April 1887, at a time he characterized as “a new educational era unfolding.”

“The country had, as a whole, entered upon a period of self-discovery,” Crowell wrote in a collection of personal reflections on his time at Trinity, commenting on the commercial explosion seen during the Industrial Revolution and the social upheaval that took place after the end of the Civil War. “It was, in short, the beginning of a period of great local, state, national and international problems.”

Crowell understood the important role of colleges and universities in such unprecedented times, writing that “at no other period in the country’s history had the educational institutions of higher learning taken a more active part in the discussion of these problems and in the resulting policies.”

The 28-year-old Yale graduate was eager to guide Trinity through this changing educational landscape, having accepted the position without ever visiting campus. He was inaugurated in June 1887, after which he pioneered a number of advances in the college’s educational and cultural pursuits.

Three months after officially taking office, Crowell spearheaded the creation of Trinity’s first library, cataloging each book himself. He also saw the college through a period of pronounced academic growth, with several new faculty hires, added course offerings and increased publications from both faculty and students.

The following year, the president coached the college’s football team in their first-ever game, defeating the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in a resounding 16-0 match-up that marked the first Southern game played in accordance with new rules set by the American Intercollegiate Conference.

In September 1892, Trinity relocated to Durham. The move was sponsored by donations from tobacco industry giants Washington Duke and Julian Carr, which Crowell hoped would abate the college’s long-running financial woes.

However, this optimism turned out to be unfounded, as Trinity soon entered a financial crisis that — coupled with growing faculty dissent — prompted Crowell to offer his resignation in June 1893. He believed that “the responsibility for adequate funds lay to no small extent with the Trustees” and that “hitherto, their habit had been to rely on the President altogether too exclusively.”

But the Board unanimously refused Crowell’s resignation, and he agreed to continue in the role on the condition that they issue a public statement of confidence in his leadership, source additional funds for faculty salaries and provide him with “a free hand in intercollegiate athletics.”

Yet even after the agreement, the Methodist Church sought to prevent the college’s participation in intercollegiate athletics. Crowell offered his resignation again in May 1894 and was ultimately successful, despite the Board’s attempts to convince him to reconsider.

Crowell later enrolled at Columbia College in New York to receive his doctorate in economics and sociology. He worked as a financial consultant in the private sector for many years, eventually becoming an associate editor at the Wall Street Journal and later the director of the World Market Institute. He died in 1931.

John Kilgo, 1894-1910

The trend of preacher-presidents at Trinity College continued with Kilgo, who followed in the footsteps of his Methodist minister father by preaching throughout North Carolina for many years.

Born in 1861, Kilgo struggled to attain a quality education during the ongoing Civil War. An article on Kilgo’s life published in the Methodist Quarterly Review explained that “good schools were scarce, and when one was found, the changes of the itinerancy prevented him from staying long in attendance.”

Kilgo first entered college at age 19, attending Wofford College in South Carolina. However, he soon gave up his studies due to his failing eyesight, with the Methodist Quarterly article noting that “uninterrupted application to books did not agree with his constitution or or meet the requirements of his type of mind.”

After a brief teaching stint, Kilgo returned to Wofford the next year and completed his degree in 1882. He also served as the college’s financial agent, working to increase the school’s endowment and community presence.

Kilgo was unanimously elected to lead Trinity in July 1894, two months after Crowell’s resignation was finalized. After delivering sermons at two Methodist churches on his first day, he “immediately impressed the people of Durham with his ability as a preacher and an educational leader, demonstrating that he had a strong hold on Methodism in the state.”

Kilgo was a strong proponent of religious education. He advocated against state funding for secular schools in his first year as president and founded a monthly newspaper, the Christian Educator, which ran until 1898.

Women were first admitted to Trinity “on equal footing with men” under Kilgo’s leadership in 1897, the result of a $100,000 grant from recurring benefactor Washington Duke.

In 1898, the Kilgo-Gattis Affair threatened to undermine Kilgo’s presidency. Kilgo incurred the wrath of Supreme Court Justice Walter Clark, a member of Trinity’s Board, when he gained trustee approval for a faculty tenure plan in Clark’s absence. The justice also generally disapproved of Kilgo’s progressive vision for the college, accusing him of being a puppet of the Duke family.

Clark submitted a formal allegation against Kilgo for “malfeasance in office,” but the president was protected by the Board’s endorsement. Clark then turned to personal attacks, which were believed to be funneled through Methodist minister and bookseller Thomas Gattis. Kilgo responded with attacks of his own, prompting Gattis to bring a slander suit that resulted in high damages paid by Kilgo despite the case’s ultimate dismissal.

Trinity’s charter underwent a change in February 1903 during Kilgo’s tenure, providing for board members to be elected by alumni and members of the North Carolina Conferences of the Methodist Church. Previously, members were selected by existing trustees.

Kilgo’s term was mired by scandal again in October 1903 with the Bassett Affair. Professor John Bassett, a long proponent of historical study that relied on primary source evidence in place of personal “pride and loyalty,” drew criticism when he ranked Black author and orator Booker T. Washington second in a list of prominent Southerners of the century.

Democratic state politicians, some of whom sat on Trinity’s Board, demanded that Bassett be fired in response to an explosion of public outcry, with some concerned parents withdrawing their children from the college. Bassett offered his resignation, but the Board voted in December 1903 to keep him on staff.

Many students had been eavesdropping on the Board’s debate over the matter through skylights and celebrated the decision. It later came out that Kilgo, alongside the college’s entire faculty, had threatened to resign if Bassett was removed.

The next year, President Theodore Roosevelt praised Trinity’s courage in standing for academic freedom at an address in Durham.

Kilgo left office in 1910 after being elected a bishop in the Methodist Church. Trinity finally overcame its history of financial struggles under his leadership, growing into “one of the best known and most richly endowed institutions in the South.”

Kilgo served on the college’s Board of Trustees from 1910 to 1917 after stepping down from the presidency, holding the role of chairman in his final year. He died in 1922.

Zoe Kolenovsky is a Trinity junior and news editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.