In honor of Duke’s Centennial, The Chronicle is highlighting pivotal figures and events throughout the University’s history. Here, we continue our look at Duke’s presidents:

From long before its founding in 1924, Duke’s administrative policies and sense of collective identity have been powerfully shaped by the vision of its many leaders over the years.

To commemorate the University’s hundred-year milestone, The Chronicle is looking back on Duke’s presidents — each of whom guided the Blue Devil community through times of crisis and celebration, charting a distinct course toward the internationally acclaimed institution that stands today.

In the second installment, we review the next five presidents who spearheaded significant expansions to Duke’s academic programs and campus while seeing the University through several administrative scandals.

William Few, 1910-1940

Few guided Duke through several major changes to the University’s structure during his 30-year tenure. He was also the modern institution’s first official president, as his administration oversaw Trinity College’s transition to Duke University in 1924.

Prior to being named president in November 1910, Few joined the faculty in 1889 as a professor of English. He later became “Manager of Athletics” and was named the first dean of the college in 1902. He held a bachelor’s degree from Wofford College in South Carolina, as well as a master’s degree and doctorate from Harvard College.

Few saw Trinity through World War I from 1914 to 1918, which induced major changes to campus life. Crops were planted on campus to aid with food conservation, drill sessions supplanted physical education courses and Trinity became a Student Army Training Corps unit.

Few was instrumental in facilitating James B. Duke’s generous $40 million donation to the college in 1924: the Duke Endowment Indenture of Trust. After its renaming, the school received 32% of the endowment’s net income alongside other educational institutions, hospitals and the Methodist Church. The move was made official Dec. 29, 1924, after a vote of approval from the Board of Trustees.

“I am sure I speak for all our Southern institutions and our Southern people when … I say that we are more and more ready and determined to take our rightful place in the house which our fathers had so much to do with building and contribute our part, as those who lived here before us contributed their part, to the greatness of our common country and to the service of mankind,” Few wrote in an address on “An Old College and a New University.”

In 1930, the new West Campus officially opened, built on land acquired by Few with the aid of James Duke. The school’s original location, now East Campus, became the Woman’s College. The president maintained that female students had “every right which the men possess” and that all who “present the proper requirements may enter any course on the men’s campus.”

The same year, Few oversaw the creation of the School of Medicine and Duke Hospital. Under his stewardship, Duke later established the School of Forestry in 1938 and the College of Engineering in 1939.

Few died in 1940 at age 72 after five decades of service to the University and was buried in the Duke Chapel crypt.

Robert Flowers, 1941-1948

After graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1891, Flowers decided to pursue a career in education instead of entering the armed forces. He joined Trinity’s staff as a professor of electrical engineering and mathematics and remained at the institution for the remainder of his professional life.

In 1925, Flowers was named the University’s vice president for business and also served as secretary-treasurer. He became a trustee of the Duke Endowment the following year and was appointed to the Board of Trustees the year after that.

Two days after Few’s death in October 1940, Flowers was named interim president. He was officially elected to the permanent role in January 1941.

Flowers was widely viewed as an apt successor to Few, whose impressive 30-year term had been widely celebrated. One account of the leadership transition lauded Flowers as a “widely admired and even loved man” whose “devotion to to Duke as well as to Methodism and its causes matched that of Few.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Not everyone was as complimentary of Flowers. Harvie Branscomb, then-dean of the School of Religion, once asserted that Flowers prioritized the establishment of “football and baseball teams that would defeat the University of North Carolina [at Chapel Hill]” above all else.

It is true that under Flowers, Duke failed to maintain the impressive growth previously attained during Few’s tenure. But although the University’s stagnation was attributed in part to Flowers’s advanced age, as the president took office at age 70, it was also seen as “more or less inevitable” due to the nation’s involvement in World War II.

The war began to impact campus life in 1941 when male students were first drafted and several members of the University’s faculty and staff took indefinite leaves of absence to serve in the federal government and the armed forces. The Duke community also experienced sugar and meat shortages and reduced social programming as a result of the war’s toll on resources, and air raids on campus were not uncommon.

In spite of the war’s intrusion on daily life, University administration attempted to preserve a sense of normalcy on campus. A February 1942 issue of The Chronicle lamented the faculty’s “trying so hard not to lower their academic standards because of pity for war-bewildered students that they ended up by cutting a bloody swath through the undergraduate ranks during the recent exam period.”

Many Duke students soon grew restless, troubled by the “spiritual and mental anguish” of feeling that they were shirking their patriotic duty by remaining in school and “contributing absolutely nothing to the war effort.” Several turned to the administration as a recipient for this discomfort.

“Duke University is failing the first great test of its existence; it is standing still at a time when it should be moving ahead; it is missing an opportunity for educational leadership that may never come again,” reads a November 1942 Chronicle editorial.

However, it was the faculty who ultimately entered into conflict with the Flowers administration in 1943 with a request to form a faculty governance structure. Flowers initially ignored the demand for several months before later responding that such a conversation would have to wait until the war ended so faculty members called away to duty could participate. Moreover, he argued, wartime travel restrictions made it difficult to convene the Board for a meeting to discuss the matter.

The question of a faculty senate resurfaced in 1946 following the end of the war and a newly published report by a Harvard economist, which stated that faculty salaries at several prominent colleges and universities in the U.S. — including Duke — failed to keep pace with the wage increases of other professions. However, faculty governance would not take shape at Duke until the creation of the Academic Council in 1962.

Race relations also became a contentious subject on campus during Flowers’s term, as some students called the Southern status quo of segregation into question. Flowers, who had previously served as chairman of the board of the North Carolina College for Negroes, now North Carolina Central University, had “a strong record of interracial activity and paternalistic concern.” Nevertheless, he continued to uphold Duke’s segregation policy throughout his time in office.

In 1946, concerns about Flowers’s advanced age began to circulate with greater fervor. Although Duke mandated retirement for faculty at age 69, no such limit existed for administrators, and community members feared Flowers and other mature University leaders “somehow missed their cues for a graceful exit and remained on stage too long.”

In May 1947, the Board broached the topic of an age cap for administrators, which was implemented the following year. Flowers voluntarily retired in 1948 and transitioned to the role of chancellor, a newly created advisory position he held until his death in 1951.

A. Hollis Edens, 1949-1960

Arthur Edens, who went by his middle name “Hollis,” was born in Livingston, Tennessee, in 1901. Described as a “mountain boy” in his youth, he reportedly rode a horse six miles to attend school every day.

Edens received a bachelor’s degree at Emory University and a doctorate at Harvard University, working a wide array of manual labor jobs along the way to pay for his education. He also served as a pastor at several country churches during this time, following in the footsteps of many of his Duke predecessors.

In 1926, Edens returned to Cumberland Mountain School in Tennessee, which he attended as a child. He quickly rose in the teaching ranks, becoming the school’s principal in 1930. He went back to Georgia in 1937 to serve as associate dean of Emory Junior College and by 1947 had become vice-chancellor of the entire University System of Georgia.

Edens was inaugurated president of Duke in October 1949, the first to assume the role without previously holding a position on the University’s staff in 55 years.

Hoping to avoid the age problem they faced with the last president, the Board intentionally selected a younger leader in the 48-year-old Edens. He was also viewed as primed to take the University to new heights — a native southerner and former executive with the Rockefeller Foundation who the trustees hoped could forge new institutional connections and develop Duke’s programming.

Edens quickly took charge, and his appointment sparked “a new spirit of hopefulness on campus.” Much of his efforts centered around boosting fundraising for the University.

Since its official founding in 1924, Duke drew the lion’s share of its financial support from the Duke Endowment. But after the Great Depression and World War II depleted the University’s coffers, it was up to Edens to begin a campaign of “systematic, well-publicized fundraising.”

Throughout his tenure, he helped drive fundraising efforts begun by trustees just before he assumed the presidency, including a Loyalty Fund aimed at procuring regular alumni donations and a special campaign to raise $12 million by 1952. Although the campaign fell short of its goal, the $8.6 million that was raised went to bolstering the academic budget and funding new building construction.

Resulting improvements to Duke’s operations included the establishment of the James B. Duke endowed professorships and the completion of the Allen Building in 1954, which was designed by architect Julian Abele to house the University’s administrative offices and remains an iconic part of West Campus’s topography to this day.

Duke also received nearly $6 million from the Ford Foundation in the mid-1950s, with $2.3 million earmarked for faculty salary raises, $2.7 donated to the Medical School and another near-$300,000 given to support other programs.

Edens’s presidency took a turn for the worse in 1960 with the Gross-Edens Affair. The event was the second of three major administrative shake-ups in Duke’s history, joined by the delicate matter of ending Flowers’s administration in the 1940s and President Douglas Knight’s abrupt resignation in 1969.

Edens named Paul Gross to the vice presidency in one of his first moves as Duke’s president, before he had even arrived on campus. University leadership supported the decision, viewing Gross’s long history on faculty in the chemistry department as an appropriate balance to Edens’s newcomer status.

Edens and Gross worked well together for years, but tensions emerged in 1955 when Gross sent his administrative partner a lengthy letter expressing concern over the University’s leadership. In particular, he noted that his participation in “overall financial decisions” had been less than satisfactory and that several administrative departments had long suffered communication breakdowns.

Gross’s dissatisfaction grew, leading to a second memorandum in 1957 addressed to the University’s executive committee restating these concerns. Upon discovery of the memo, Edens was troubled by the feeling that Gross seemed to be pushing for major administrative changes without consulting him.

The two University leaders met several times in early 1958 in an attempt to resolve their differing administrative visions but made little headway.

An internal faculty committee formed by Edens highlighted a number of lingering problems with Duke’s administrative structure. The resulting 1959 report found that the University’s bylaws did not define well the responsibilities of administrative offices and that faculty voices were not adequately represented in policy decisions, also noting that there had been no prior review of the administration’s functioning since Duke’s founding.

In late fall of the same year, the newly appointed chief representative of the Board, Thomas Perkins, suggested to Edens that he transition from the presidency to a chancellorship. Edens struggled with the notion for several months, but in February 1960 eventually offered his resignation.

Edens’s public announcement of his resignation at a specially called faculty meeting later that month sparked shock and alarm among faculty, students and trustees. Details of the ongoing tensions between Edens and Gross — previously unbeknownst to the vast majority of the Duke community — began to emerge through reporting by local North Carolina newspapers.

In March, a contentious discussion by the Board culminated in their request that Gross give up the vice presidency. He remained on staff as William H. Pegram professor of chemistry until his retirement in 1965.

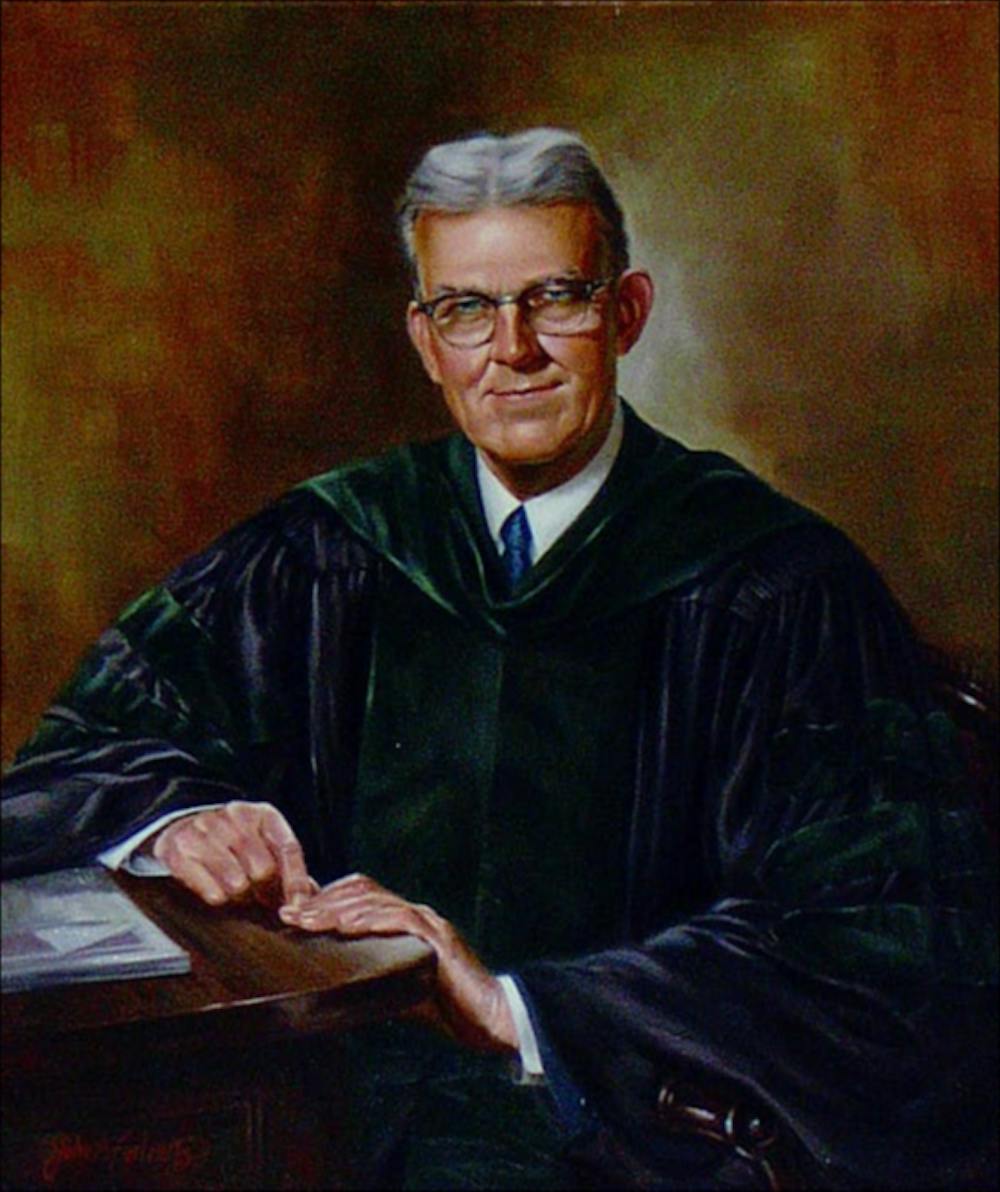

J. Deryl Hart, 1960-1963

Julian Hart, who went by his middle name “Deryl,” was born in Prattsburg, Georgia in 1894. He grew up on his family’s farm before attending Emory, where he received bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

While Hart excelled in mathematics, he resolved in his senior year of undergraduate studies to become a doctor. He received a Doctor of Medicine from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1921, where he stayed to rise in the surgical staff ranks.

In 1928, Duke offered Hart the positions of professor of surgery and chairman of the department at its School of Medicine and Hospital. He assumed the roles in 1930 after construction was completed on the facilities.

Hart excelled at Duke, with an impressive clinical history that left him respected by students and patients and contributed to the school’s budding national prestige. He helped pioneer the Private Diagnostic Clinic, which now exists as the world-renowned Duke Health Integrated Practice as of July 2023.

Hart also served on the board of governors and executive committee of the American College of Surgeons and as vice president and later president of both the Southern Surgical Association and as the Southern Society of Clinical Surgeons.

In April 1960, he took over from Edens as president pro tempore of Duke, scheduled to officially begin his term July 1. The Board named Hart the University’s president in March of the following year.

Much of his brief tenure was focused on repairing relationships between administrators, faculty and trustees following the scandal that marred the end of Edens’s presidency — an endeavor he was largely successful in. He redefined a number of administrative offices to improve efficiency and established the Academic Council in 1962 to give faculty a role in governance.

Hart also oversaw a number of expansions at Duke, both to the physical campus and to its faculty and student body. Under his leadership, faculty salaries were substantially raised and the number of endowed professorships doubled.

Following the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling mandating the desegregation of public schools across the nation, private colleges and universities like Duke were slow to change their own policies. It wasn’t until Hart took the reins that the University opened its doors to students of color, first at the graduate and professional schools in 1961, then at the undergraduate colleges a year later.

Hart retired from the presidency in 1963, having guided Duke through several monumental changes despite only serving in the role for a short period of time. He died in 1980 at the age of 86.

Douglas Knight, 1963-1969

Douglas Knight was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1921. He attended Yale University, where he received bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in English. He taught at Yale until 1953, when he was named president of Lawrence College in Wisconsin at only age 32.

After 10 years at Lawrence, Knight was named Duke’s fifth president and inaugurated in December 1963.

Knight continued the trend of grand development for the University in the mid-20th century. He established programs for joint M.D.-J.D. and M.D-Ph.D. degrees, as well as interdisciplinary programs in biomedical engineering and forestry management. He also oversaw the addition of a phytotron and a hyperbaric chamber, a major renovation to Perkins Library that increased capacity fivefold, the conversion of a science building on East Campus to an art museum and the construction of Central Campus to connect the women’s and men’s colleges.

Supporting these expansions was $195 million in gifts and grants that Duke brought in during Knight’s tenure — three times the amount received during the previous six-year period.

Behind much of the fundraising was the Duke $102 Million Campaign, chaired by George Allen, a longtime trustee of both the University and the Duke Endowment. The campaign aimed to raise funds for Knight’s “Master Campus Plan,” which would propel Duke to become not only “a force in the South” but “a force in the nation.”

In 1966, Knight was appointed chair of the National Advisory Commission of Libraries by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Despite these significant advances, Knight’s tenure is most known for the 1969 Allen Building Takeover that resulted in his eventual resignation.

While the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s had thrown much of the South into social and political turmoil, Black students at Duke — who had only just been allowed to enroll starting in 1965 — felt the University was not doing enough to support the cause.

At 9 a.m. Feb. 13, between 50 and 75 Black students occupied the Allen Building in a powerful show of student dissent. They delivered 11 demands to the administration, among them to enroll a greater number of Black students and to establish an African American studies department.

The students remained in the building until 5:15 p.m. despite demands from administrators to leave. Knight decided to call in Durham Police and the National Guard, and the ensuing confrontation resulted in the clubbing and tear-gassing of several students.

“I do not and cannot condone the illegal occupation of any building on any university campus for any reason at all,” Knight said in a Feb. 15 statement for WDBS Radio. “This sort of action, this sort of aggressive action is no way in which to resolve a problem. It simply compounds it.”

Knight announced that a committee aiming to improve the experience of Black students on campus had already formed in October of the previous year, and an additional task force was established shortly before the takeover. Negotiations between students and administrators continued with little movement through March, prompting students to stage a demonstration in downtown Durham.

On March 19, a University hearing found the students guilty of violating University regulations and sentenced them to one year of probation. The penalty was reduced from the original threat of expulsion after students refused to name those who participated in the sit-in, opting to share the blame to prevent the administration from singling out students for greater punishment.

Knight submitted his resignation March 27, citing the need “to protect [his] family from the severe and sometimes savage demands of such a career.” His time at Duke concluded June 30.

Knight next served as vice president of educational development for the electronics company RCA Corporation, and later president of RCA Iran in 1971. He was named president of industrial manufacturer Questar Corporation in 1976.

In 2003, Duke renamed the president’s house after Knight and his wife, Grace Knight. Knight had been the first president to live in the house and oversaw its completion in 1966. He died in 2005 and was remembered by then-President Richard Brodhead as “a man of great wisdom and generosity.”

Zoe Kolenovsky is a Trinity junior and news editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.