“What’s your destiny?”

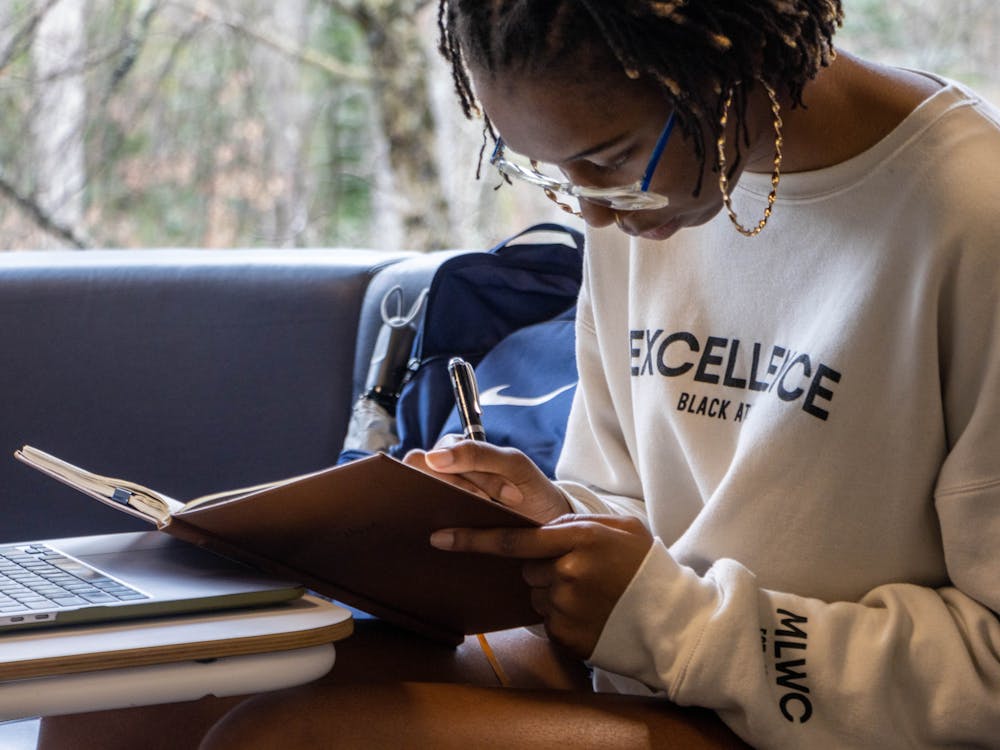

That is the question junior Destiny Benjamin asks everyone she interviews for her blog, fittingly titled “What’s Our Destiny?”

According to Benjamin, her destiny is to “show love in any capacity and to show love in ways that better the Black community." Although her question focuses on the future, Benjamin has already made an impact in uplifting the Black community on Duke's campus.

Her passion for making the world a more equitable place originates from her admiration for civil rights activist Malcolm X, whose historical legacy she seeks to redefine — from that of an antagonist to someone who enacted positive change for the Black community.

To those who know Benjamin, Malcolm X is a constant reminder of who she seeks to embody in her activism. A poster of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. hangs proudly in Benjamin's dorm, with others of Angela Davis and Tupac Shakur nearby. Her iPhone screensaver is a picture of Malcolm X, and her Instagram bio includes a quote by the activist: “You don’t get freedom peacefully.”

For Benjamin, these activists are not just people of history, but those who she constantly seeks to embody and honor through her work.

‘Take up the mantle’

Benjamin seeks to “take up the mantle” from civil rights activists such as Malcolm X, King and Fred Hampton who “died too young” and finish what they started.

“It's hard to live up to what they do, but that's definitely what drives me,” she said.

To guide Benjamin in her effort to redefine the way Malcolm X is presented historically, Destiny's father, Marcus Benjamin, suggested that she start a blog. There, she could use her platform to both examine Black history and its legacies and shape the future of what she envisions the Black experience to look like.

But it wasn’t just her father who recommended that she pursue this project — after listening to Destiny talk about her passions, her college advisor also brought up the idea. To many, this was just a natural next step for her to take in her journey.

With the help of her father, Destiny started “What’s Our Destiny” on May 19, 2020 — Malcolm X’s birthday.

Destiny's blog touches on figures and milestones that have influenced Black history on all fronts, from author Langston Hughes’ impact on the literary world throughout the Harlem Renaissance to Black women in the reproductive rights movement.

While honoring these trailblazing figures and events, Destiny tries to incorporate Malcolm X in each piece, hoping to challenge the narrative of Malcolm X being an “antagonist” in the history books.

“Destiny set out to change that historical narrative and in the process of doing that, she found herself impacting the present times by uncovering the truth and providing clarity to the historical influence that Black and Brown people had on our country,” wrote Destiny’s mother, Omeka Benjamin, in an email to The Chronicle.

What began as a passion project at the end of her junior year of high school turned into Benjamin expanding her presence on social media, using it to conduct interviews across campus. She's also begun planning events like “Revisiting the Takeover: A Commemoration of the 55th Anniversary of the Allen Building Takeover.”

Behind the scenes of the recreations and the panel

Before stepping foot on campus her first year, Benjamin said she knew little about Duke’s Black history.

That quickly changed. As an African and African American studies major, Benjamin said her classes often touch on Black history at Duke and how it has shaped the University in the present. In particular, she said that nearly all of her classes referred to the significance of the Allen Building Takeover in 1969, during which Black students protested their treatment on campus in front of administrators’ offices.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

What ultimately caught Benjamin's eye when first learning about the takeover was the central role the Malcolm X Liberation School — an experimental educational institution inspired by the Black Power and Pan-Africanist movements — played in the protests. Discovering Malcolm X's connection with Duke pushed her to "delve deeper into that history."

Benjamin noted that as Duke celebrates its centennial, it is important to recognize how Black history overlaps with Duke’s overall history. Duke officially desegregated 62 years ago in 1961, following the 1954 Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The federal government threatened to withdraw its funding and grants if Duke did not integrate.

“I think it's important that even though Black students haven't been here all 100 years, we are still an important part of Duke's history,” Benjamin said. “We're still an influential part of the Centennial … I think Black students deserve to be a part of that.”

So, she got to work.

She initially intended to recreate photos with current Duke students as models from the Duke Library Archives to post on her blog and social media platforms. During a meeting between Benjamin and her mentor and professor Candis Smith, interim vice provost for undergraduate education and professor of political science, to bounce ideas around about how she could uniquely and powerfully capture the impact of the takeover in the present, Smith suggested that Destiny could also host a panel featuring the original activists.

Starting in November, Benjamin worked closely with representatives from Duke Libraries, Duke Arts and the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture to access the library archives from the 1969 Takeover, organize logistics for a photo exhibition and contact around 50 models for the photos.

She finally met University Archivist Valerie Gillispie, who guided her in navigating the archives to find the photos she wanted to recreate.

Benjamin then curated her vision, hoping to loop together the past Black student experience with that of the present to honor the ongoing process of Black liberation. This vision was clear to those who worked with her.

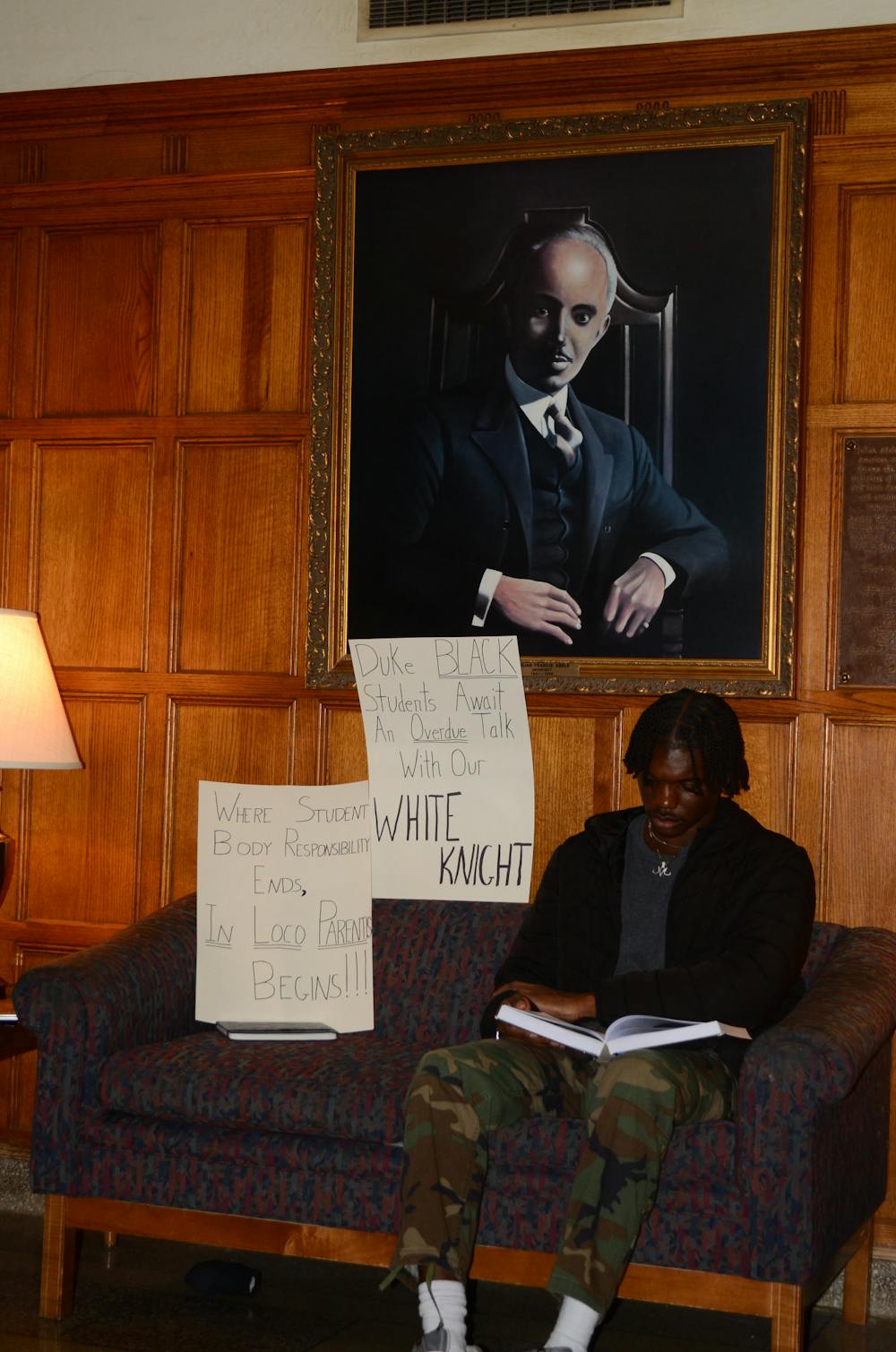

“It was a re-creation but … it was an adaptation as well, because you know … [there] is a MacBook [in some of the photos],” said sophomore Joe Asamoah-Boadu, a model in Benjamin's project. “So I just feel like we are recreating it but also adapting it for the time.”

In recreating one photo of a student protesting during the study-in, Benjamin found that the original art piece behind a student in the Allen Building was a painting of a tree. However, when she went to recreate the photo, she saw that a portrait of Julian Abele, the Black architect who designed the University, was displayed in its place. She chose to recreate the photo in front of that painting to showcase the powerful impact Black figures have had on the University throughout its history.

The painting of Abele reflects a “small example of this change [and] this growth that we've seen” at Duke, Benjamin said.

Senior Hassan Ali, the photographer for the project, noted how Benjamin's clear vision enabled him to capture exactly what she had in mind.

“She was just so clear on what she wanted,” Ali said. When it came to taking the photos, he said it was as simple as discussing how he could adjust his camera settings to create a product that fit Benjamin's vision.

Despite this clear sense of direction, managing busy students’ schedules and other logistics of the project was not as simple as Benjamin anticipated. While recreating the Malcolm X Liberation School shot on Chapel Drive, Benjamin, Ali and around 30 student models had to dodge the continuous loop of C-1 buses driving by. Attempting to capture that perfect photo in the January cold did not make that process any easier.

“We were fighting with the buses,” Ali said. “[It was also] really cold, my hands were numb, and I know, [the models’] hands were numb. But we got it done.”

Benjamin recreated another photo of two Black students looking out a window in the Allen Building. Ali also noted that he was forced to adapt his photography to try and hide the window screen, which was not present during the original takeover.

“I was just kind of really messing around with a lot of the highlights, the exposure, the contrast, and I think that it turned out really great,” Ali said. “I think it is probably one of the most iconic, in my opinion, from the recreations.”

While organizing the panel, Benjamin tapped into different resources across campus to help her with administrative planning and logistics.

Gillispie helped Benjamin reserve the Rubenstein Library’s Holsti-Anderson Family Assembly Room to host the panel and connected her with alumni who participated in the original takeover, while Smith helped her flesh out the logistics of her project. Those who assisted Benjamin shared that her clear vision allowed them to effectively help her behind the scenes in the “nitty gritty administrative areas.”

“Destiny single-handedly brought together a key set of stakeholders to the table to bring the event to fruition — Duke Libraries, Duke Arts [and] the Mary Lou Williams Center,” Smith wrote in an email to The Chronicle. “In each of these units, people saw how organized, careful and thoughtful Destiny was, and pitched in to bring this fantastic event to life. The event required both collaboration and Destiny’s leadership.”

“She really made sure that it was … a conscious effort. It wasn't haphazard at all,” Asamoah-Boadu said. “She had a vision to not only revisit the takeover, but [to] inspire future advocacy.”

The future of the Black experience at Duke

Benjamin noted that while much progress has been made for the Black experience at Duke, there is still work to be done to ensure that Duke continues to acknowledge its history and ongoing treatment of Black students, faculty and staff.

“We tend to think about ‘history’ as being long gone, but many of the people who took part in the Allen Building lock-in are still alive and continue to contribute to Duke’s story in the making,” Smith wrote. “Indeed, in addition to the four alumni panelists, several other Duke alumni who played a part in the lock-in attended the commemorative event, sharing their experiences and hopes for Duke’s future.”

Benjamin recognizes that if it were not for movements like the Allen Building Takeover, she may have not been able to major in AAAS. During the 1969 takeover, students called for the creation of a Black Studies program as one of their 13 demands. The program, now known as the AAAS department, was approved just one year later.

Samaiyah Faison, assistant director of the Mary Lou Williams Center, wrote in an email to The Chronicle that the birth of institutions such as the MLWC is due in large part to events like the Allen Building Takeover. She added that Benjamin's ability to recognize these connections compelled her to pursue this project to educate current and future generations of Black students at Duke.

For Benjamin, remembrance is important, especially as Duke celebrates its centennial. She noted how she thinks Black history is often ignored or “whitewashed and represented incorrectly,” which she connects to the historical representation of Malcolm X. With her panel, she wanted to make sure that the takeover is remembered by Duke correctly.

In speaking with the panelists, it became clear to Benjamin the detailed work and planning that went into the students’ preparation for the takeover.

“It wasn’t students who one day just chose a date and were like, let's just go in, [but] we don't really know what we're gonna do when we get in,” Benjamin said. “This happened weeks, probably months or so [in advance].”

According to Benjamin, Black history events at Duke are typically hosted by the Mary Lou Williams Center or organized by other inspired Black students like herself.

To Benjamin, this represents a lack of recognition by the University of the importance of honoring its Black history, which has led her to question whether more positive change will ensue. She noted that she had to “fight for recognition” for her panel to be listed as a part of Duke’s centennial celebration.

“I think that's the difficult part because, yeah, I'm really proud of this project. I'm really proud of the results that we've seen from it,” Benjamin said. “I've gotten so many positive responses from administration, students and so many different people. But it's just like, [are] things actually going to change?”

Abby Spiller is a Trinity junior and editor-in-chief of The Chronicle's 120th volume.