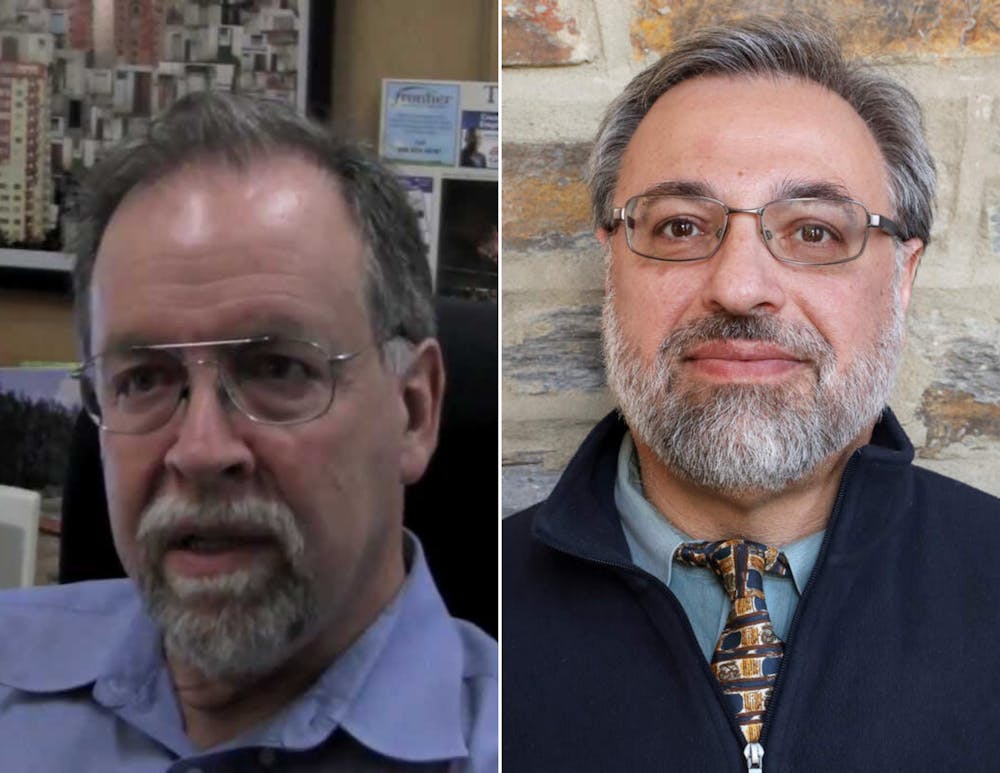

On the morning of March 14, Erik Zitser, librarian for Slavic, Eurasian and East European studies and adjunct assistant professor in the department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies, received a phone call from a reporter asking what he thought about his inclusion on a list of U.S. citizens sanctioned by the Russian government.

His initial reaction was “shock and disbelief, as if I had suddenly found myself in an episode of ‘The Americans,’” Zitser wrote in an email to The Chronicle.

Announced in a statement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Zitser and Charles Becker, research professor of economics, along with 225 other American citizens, were banned from traveling to Russia and would be sanctioned if they ever tried to enter the country.

“The ban applies to those involved in conceiving, carrying out and justifying the anti-Russia policy adopted by the current administration of the United States, as well as those directly involved in anti-Russia undertakings,” the statement reads.

“The decision is part of retaliatory measures in response to the massive and constantly expanding list of sanctions imposed by the American government on Russian citizens for supporting the Kremlin and the special military operation.”

The list comprises various U.S. citizens across the country with various levels of involvement in Russia, from a deputy U.S. trade representative to over 30 other professors who the Russian government says “have regularly made hostile statements or spread far-fetched allegations and outright slander about Russia’s domestic and foreign policy.”

This decision follows declarations by the Russian Foreign Ministry banning 56 Canadian citizens and 18 members of the United Kingdom’s military, political, scientific and academic communities.

Both members of the Duke community speculated that their work adjacent to Ukraine and Ukraine-related issues may have been part of the reason they were put on the list, but they have no definitive answers.

“Only the bureaucrats who drew up the Foreign Ministry list really know how my name ended up on it,” Zitser wrote. “And until the Foreign Ministry archives are opened to researchers, there is no way to be sure how the list was drawn up.”

Given that his work is primarily outside Russia, Becker suspects his place on the Kyiv School of Economics board earned him a spot. Similarly, Zitser assumes his role at Duke, a U.S. research institute “targeted by the Russian Foreign Affairs Ministry in this round of sanctions,” put him under scrutiny.

“The choice of candidates, however, seems to have been made arbitrarily and unsystematically,” Zitser wrote. “Many of the scholars who are most vocal in critically analyzing the conflict in Ukraine were inexplicably left off the list, while at least in one case, the compilers added the name of a center administrator.”

Zitser received his Ph.D. in Russian history from Columbia University and worked as a postdoctoral fellow, center associate and librarian at Harvard University’s Center on Russian and Eurasian Studies.

He works to describe, develop and activate Duke’s Slavic collection, including its Ukrainian language holdings.

“It is anyone’s guess whether my attempt to respond to the popular demand for reliable information about what was going on at the start of Russia’s military invasion and the online coverage that my public outreach efforts received in official university publications, such as Duke Today, brought my professional activity to the attention of Russian government officials,” Zitser wrote.

On the other hand, Becker researches topics ranging from economic demography to trailer parks in the United States. Little of this research involves Russia.

Becker only found out he was on the list after a friend emailed him, he said.

Becker joined the International Academic Board of the Kyiv School of Economics in 2005. In his role there, he advises students on going to graduate school abroad and faculty on developing their careers. Despite his diminishing involvement in the role and decreasing demand for advising, he suspects the appointment earned him a place on the list.

Receiving the news was “disheartening,” Becker said. “I’m old enough to remember what the Cold War was like.”

Neither sees this as having a tangible effect on their ability to conduct research and fulfill their roles at Duke. However, they say it speaks to the strained global ties between the U.S. and Russia amidst the war in Ukraine.

"Even at this stage, however, it appears that this state-sponsored act of cyberbullying has little or nothing to do with the people on it," Zitser wrote. "They are all pawns in a game of diplomatic tit-for-tat between two hostile governments."

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“The list is an intimidation tactic typical of the Cold War,” he wrote. “And a reminder that the Cold War never formally ended.”

Jothi Gupta is a Trinity junior and an enterprise editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.