The Chronicle compiled a timeline of the events that led to the decision to close the Duke Herbarium, a move which was met with intense backlash from the scientific community at Duke and beyond.

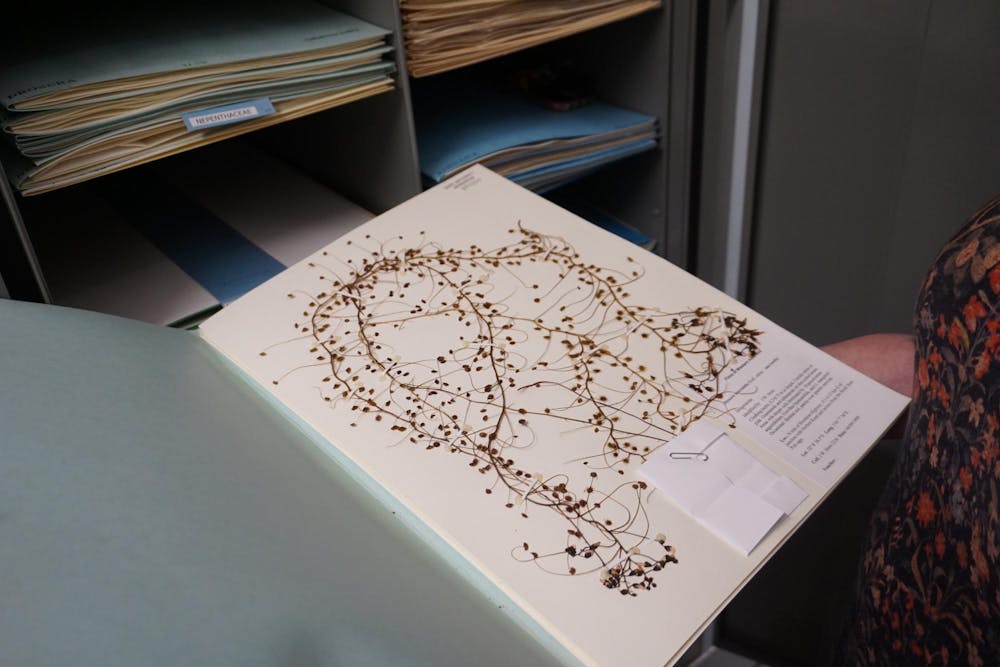

Last week, the University announced plans to close the Duke Herbarium, one of the largest such facilities in the world with over 825,000 plant specimens in its collection. Students, faculty and researchers expressed their outrage at the decision, with some arguing that the closure undermines global efforts to preserve biological data that could prove a critical resource for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.

In the months before the closure, departmental leadership limited communication with herbarium faculty about the facility’s future.

Expanding the facility

The primary location where around 400,000 of the herbarium’s specimens are currently housed — a three-level storage facility within the Biological Sciences Building — was created in the 1960s when the building was first constructed. An additional 500 specimen cases lined the hallways on all five floors of the building until the mid-2000s, when plans to build the French Family Science Center prompted administration to reconsider the Biological Sciences Building’s layout.

Specimens were moved to an off-site storage facility for four years. Professor of Biology Kathleen Pryer, the director of the herbarium since 2005, expressed that the location was less than ideal for specimen storage and presented faculty with a number of logistical problems.

“We had horrible floods, black mold caked all over the place — it was really precarious,” said Pryer, who conducted research at the herbarium as a doctoral student between 1990 and 1995 and has been on Duke faculty since 2001.

In 2006, Pryer wrote and submitted a Collections Improvement Grant to bring the specimens back to Duke’s campus, which was ultimately funded by the National Science Foundation. The University allocated space to house the specimens in the Phytotron Building and $300,000 to complete the necessary renovations, and the NSF provided the other necessary $500,000.

First signs of trouble

In 2022, Emily Bernhardt, chair of the biology department, asked professors of biology Kathleen Pryer and Paul Manos to create a “strategic plan” for the herbarium, which was completed in February 2023.

Bernhardt wrote in a Thursday email to The Chronicle that conversations about the future of the herbarium began because the department "learned that we would have to at least temporarily rehouse half of the collections to accommodate much-needed building renovations that are now in the early planning phases."

“Every chair, every dean that’s come, I’ve spent hours explaining [the herbarium] to them because they don’t get it,” Pryer said.

The report, which was obtained by The Chronicle, proposed several initiatives that could be carried out within a five-to-eight year time frame with the ultimate goal of transitioning the program from “an outdated model established and maintained over the past 70+ years to one that is modern and sustainable.”

Pryer and Manos noted that the herbarium currently operates under the supervision of five faculty members with different specialties, resulting in “competing visions” and ultimately “a diminished profile of the entire resource within the University community.”

In addition to questions of oversight, the program suffers from serious spatial constraints.

Although specimens are currently housed in two separate locations on Science Drive, the collection has exceeded Duke’s storage capacity, and staff consistently face a backlog of new material to be processed. The report found that the facility within the Biological Sciences Building has not been adequately maintained, leading to safety concerns for the specimens and researchers.

“The space has never seen any renovations and is regularly plagued by serious water leaks from outdated HVAC units,” the report reads. “Total collection space on the three floors is ~6000 sq ft, overcrowded, and has no room for future growth.”

The report’s major recommendations included centralizing leadership to a single faculty member, identifying new stakeholders to contribute to the program’s support, integrating the herbarium more visibly into biology and environmental science curricula, developing more unified fundraising protocols and strengthening outreach efforts across the University.

Pryer sent the completed report to Pamela Soltis, director of the University of Florida Biodiversity Institute, who conducted an analysis that was submitted to Bernhardt alongside the initial report.

Soltis emphasized the significance of the Duke Herbarium’s reserves as “one of the largest and most diverse collections in the United States,” serving as a crucial resource for international biological research efforts. She also noted that the herbarium has the potential to augment on-campus initiatives during the University’s centennial and offers opportunities for collaboration with institutions like Duke Gardens and the Nicholas School of the Environment, in addition to new programming for the Duke Climate Commitment.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“The Duke Herbarium is recognized by the global scientific community as an outstanding resource documenting plant diversity,” Soltis wrote. “This Strategic Plan is an excellent step forward into Duke’s second century.”

Pryer said that she “never heard a word” from administration about the report until May 2023, when she said Bernhardt mentioned in an unrelated meeting that the Strategic Plan was “not gaining traction in the administration.” She says that Bernhardt suggested that Pryer craft a “vision plan” to better explain the program’s value to administration and conceptualize areas for future improvement.

Pryer created such a plan, teaching herself how to draft basic architectural drawings to visualize a new space for housing the herbarium’s specimens, and submitted it to Bernhardt at the end of the month. Pryer says there was once again no follow-up communication from administration.

Bernhardt wrote to The Chronicle that discussions with faculty members — including Pryer and Manos' team — considered various scenarios for the future of the herbarium, ranging from Pryer's model of housing the herbarium in a more modern on-campus facility to housing the herbarium in a less accessible space off-campus that may have damaged the species, as it was in the mid-2000's.

"Among the intermediate options raised was the possibility of combining forces with other herbaria and discussing who those likely partners might be. Everyone agreed that the highest priority was to ensure the protection, expert curation and sustained use of the collections," Bernhardt wrote.

Faculty notified

While Bernhardt advocated for the best-case scenario, the department found that the funding and internal partnerships necessary for Pryer's plan were not achievable.

"It is one of many competing needs for science infrastructure and staffing investments in Trinity College of Arts & Sciences. We thus began exploring alternatives and, at that point, the decision about future funding was communicated to the herbarium faculty," she wrote to The Chronicle.

The first official announcement of the herbarium’s closure came in a Feb. 13 email from Susan Alberts, dean of natural sciences and Robert F. Durden professor of biology, to five faculty members.

“We have carefully considered the requirements to maintain [the herbarium] in the manner in which it should be maintained, which would include multiple endowed faculty and staff lines as well as state of the art facilities,” Alberts wrote. “We have concluded that because of this large set of needed resources, it’s in the best interests of both Duke and the herbarium to find a new home or homes for these collections.”

Alberts emphasized the high value of the herbarium both in terms of the scientific discipline and in maintaining Duke’s prominence as an international leader in biological research.

“We recognize that the Duke Herbarium is a highly valuable research collection, more than a century in the making. We also know and appreciate that it has been expertly curated and studied by Duke faculty and staff, and it has contributed to Duke Biology’s ascendancy among US universities in understanding the evolution of biodiversity,” Alberts wrote.

Alberts informed the faculty members — which included professors of biology Pryer, Manos, A. Jonathan Shaw, Rytas Vilgalys and Francois Lutzoni — that they would be responsible for rehousing the specimens over the next two to three years and that the department expected regular updates on their progress.

A number of faculty, staff and student researchers connected to the herbarium expressed that the administration’s decision to close the facility came as a shock.

“Why is that my job?” Pryer asked. “These are my golden years, I have projects I want to finish. I don’t want to be shipping off stuff to people, that’s unbelievable demand. It’s not in the job description … It was so callous.”

Connie Robertson, a data manager in the biology department, added that the effort to relocate Duke’s specimens is all the more intensive considering the large volume of items currently loaned out to and on loan from other herbaria that would need to be recalled, reprocessed and rehomed.

“It is an insane endeavor when you have not just one institution that you’re dealing with,” Robertson said. “Just for [the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Herbarium] alone, I think we’ve got maybe over 20 outstanding loans … so that’s a lot of people that are involved.”

Claire Cranford contributed reporting.

Editor's Note: This story was updated Thursday evening to include Bernhardt's comments.

Zoe Kolenovsky is a Trinity junior and news editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.