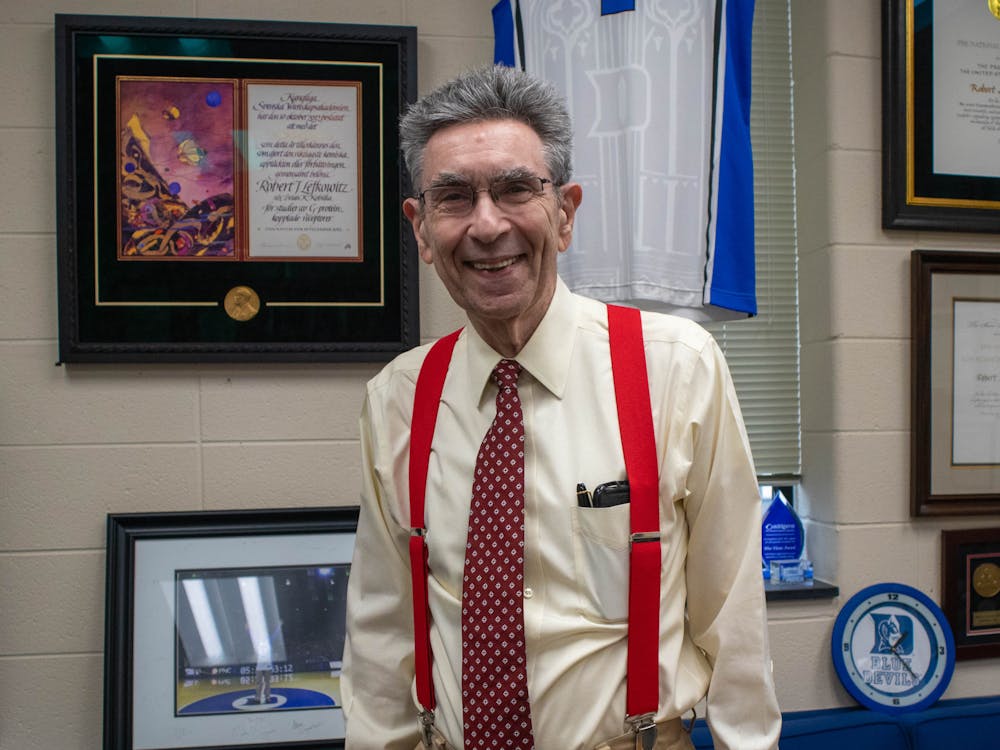

Throughout his 50 years at Duke, Robert Lefkowitz, James B. Duke professor of medicine, has discovered a family of proteins, won a Nobel Prize for his research and mentored countless students.

As the University prepares to hold a symposium in recognition of Lefkowitz's work from Oct. 2 to 3, he's excited not just for the event itself, but also for the slate of prominent speakers, which includes several other Nobel laureates.

Looking back on his career, Lefkowitz is proudest of two things — the cadre of "phenomenal scientists" who were trained in his laboratory and what he calls his "true scientific legacy," as well as "the whole body of the work that we did, rather than any one specific discovery or technical advancement."

The road to the Nobel Prize

Lefkowitz is well known for his discovery of a family of hormone receptor proteins called G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which earned him his Nobel Prize in chemistry.

When Lefkowitz was at the start of his scientific career, many were skeptical about the concept of binding sites on cells that hormones and drugs could interact with. But Lefkowitz, based on his early work at the National Institute of Health, was "convinced" that these sites existed.

"It just seemed to me intuitively, that if you could make headway initially to show that they existed, then to characterize them and learn how to leverage them and find out how they were regulated — it just seemed to me so obvious that that would have to be important and would have important therapeutic implications," he said.

When Lefkowitz began researching the existence of GPCRs, techniques to investigate the proteins did not exist yet. He spent the first five to 10 years inventing these techniques and convincing people that these receptors existed.

“Over the ensuing 10 years, we were able to actually isolate the receptors,” he said. “And then over the last 30, we've just learned a lot more about them.”

His discovery has had an immense impact on healthcare, with one study estimating that around one-third of FDA-approved therapeutics rely on GPCRs.

In 2012, Lefkowitz received a 5 a.m. call from Stockholm announcing that he had won the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

"I was, at that point, 69 years old. And I was kind of figuring, I guess it's kind of passed me by. It's just not gonna happen," Lefkowitz said.

“I must say, rather than it being like a eureka moment and feeling like jumping out of the bed and doing a jig, it was more of a quiet feeling of satisfaction,” he added.

Lefkowitz and his lab continue to work on receptor model systems relating to blood pressure and heart functions, aiming to find more effective and specific drugs based on ligand-receptor relationships.

'Never a solitary pursuit'

Along with his own research accolades, Lefkowitz describes empowering his mentees and bringing them to a point of independence as the "most gratifying part" of running his laboratory.

"I'm kind of a people person. I enjoy interacting with people. I enjoy teaching," he said. "For me, doing research and running my lab was never a solitary pursuit. What I enjoyed was the interaction with the young people and turning them on to just how exciting scientific research can be."

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Lefkowitz’s memoir, “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm,” was based on the anecdotes that he would share with his trainees. Randy Hall, one of his mentees, was a major contributor to the memoir.

“I always tell people if something's really important, you can't look it up in a book,” Lefkowitz said. “If I was going to give one piece of advice to the students, it would be whatever direction you're going, seek out excellent mentors to teach you what's really important.”

Lefkowitz credits his own mentors for leading him through his success in biochemistry. Jesse Roth and Ira Pastan, both endocrinologists at the time, were scientific mentors for Lefkowitz when he worked at the NIH for a two-year-long project.

Prior to his project at the NIH, Lefkowitz aspired to be a cardiologist. After leaving the NIH and continuing to pursue this goal, he realized that science research was where he found fulfillment.

“I missed the laboratory. I missed the day-to-day challenge,” Lefkowitz said. "Confronting scientific problems, designing experiments, getting data, revising my hypotheses, the whole process."

Since his decision to return to research, Lefkowitz has gained a new perspective on science over his 50 years at Duke, describing his everyday life as "one experiment after the other."

“As they say, I'm still standing and enjoying what I'm doing very much professionally, even at this age,” he added.

Winston Qian is a Pratt sophomore and health/science editor for the news department.