Undergraduate grade distributions at Duke have risen steadily through the 2022-23 academic year, furthering trends of high grade point averages across Trinity College of Arts & Sciences and the Pratt School of Engineering.

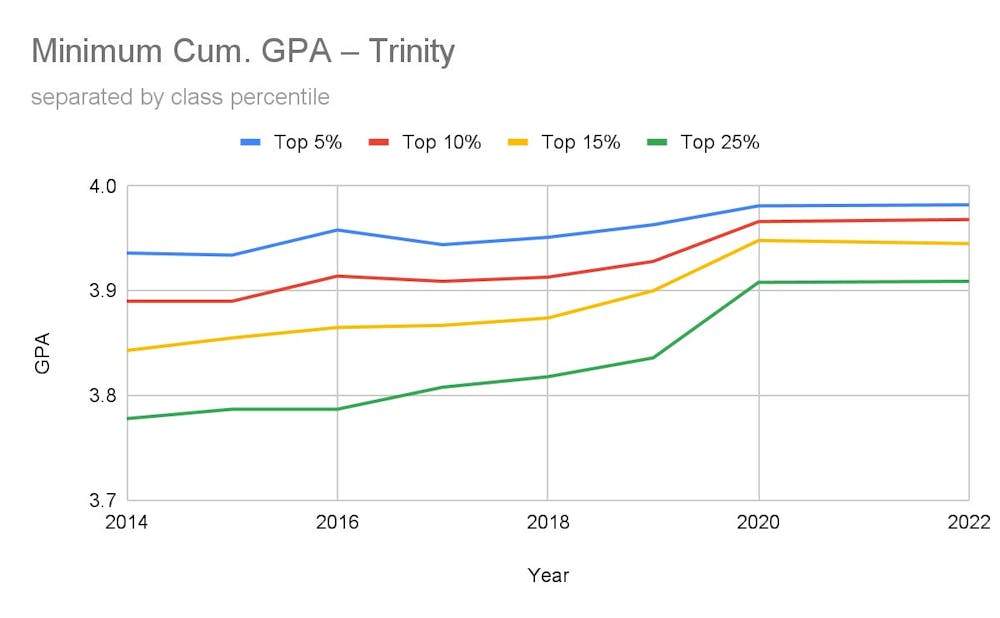

Duke’s Office of the University Registrar collects and reports class percentile data each semester, dating back to fall of 2014. This information captures the minimum cumulative GPA for students placed within the top five, ten, 15 and 25 percent of their class segmented by grade level and semester. GPA cutoffs are used to designate students who graduate with Latin honors and other academic distinctions, including Phi Beta Kappa.

Throughout eight years of publicly available data, several academic trends have persisted, including rising GPAs.

Cutoff GPAs for each percentile tier have tended to increase every year, with a notable jump taking place after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic — the spring 2020 semester and beyond. GPA levels corresponding to percentiles decrease as students progress through their time at Duke.

Frank Blalark, associate vice provost and university registrar, argued that the high GPAs reported by the registrar’s office are not a result of so-called grade inflation, but rather a continuation of past excellence.

“Analyses of grade inflation can be nuanced and challenging to describe,” Blalark wrote in an email to The Chronicle. “Historically, Duke has never had a high number of D or F grades. C grades have a statistic, but they are still outliers compared to A and B grades. Meaning, the overwhelming majority of grades for Duke undergraduates fall into the B- to A+ range, and our collective [cumulative] GPAs also oscillate around 3.500 +/-.”

At Duke’s peer institutions, GPA levels vary. A survey of 471 members of Princeton’s 2022 graduating class found that 39.3% of respondents finished with cumulative GPAs at or above 3.8. A similar survey conducted across Harvard’s 2022 graduating class found that 71.1% of respondents ended their four years with a cumulative GPA greater than or equal to 3.8.

Some GPA data, including class percentile data, is available at the Office of the University Registrar’s website as well as several other publicly available dashboards of enrollment and demographic information. More information about GPA trends at Duke, such as GPAs disaggregated by major, is either unavailable or private.

Why has the trend accelerated post-COVID-19?

Many students believe that a potential factor for increased GPAs during the COVID-19 pandemic may be an increased reliance on virtual classes and take-home assignments, giving students additional time and freedom to complete their work at their own pace — with outside resources and limited monitoring.

However, Brandon Fain, assistant professor of the practice of computer science, has another idea.

“I have not seen a consistent increase in grades in my courses over the last several semesters. However, I have roughly only been teaching since the pandemic, so it’s difficult for me to see the before/after impact of COVID specifically,” he wrote in an email to The Chronicle. “If I recall correctly, early COVID semesters adopted a policy that made it very easy to take a course on a satisfactory/unsatisfactory (S/U) basis. That may have had an impact.”

Senior Anya Gupta, who enrolled at Duke before the pandemic, agreed with Fain’s assessment. She described the prevalence of using S/U policies to preserve GPAs, and how such a strategy was not popular before the pandemic.

Some major courses at Duke have recently adopted S/U grading structures, including the introductory courses in public policy and economics. Students can also now change up one course per semester to S/U grading, which counts toward graduation and general education requirements, while still maintaining eligibility for semester honors like Dean’s List.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

To Gupta, the higher GPA cutoffs for Latin honors are “frustrating” and give employers a “really skewed” perspective that they wouldn’t be getting had she performed similarly at another school.

“I think I have probably like a 3.8, but I was looking at the website and was like, man, I wouldn’t qualify for a single one of these,” she said. “It’s crazy.”

The shrinking margin for error to achieve academic honors is also a concern for junior Chloe Decker, who says that the higher cutoffs disadvantage certain students over others.

“The cutoffs being so high takes away their relevance for many students who are pursuing majors or minors in fields that are graded on curves, or naturally don't award A's to the majority of the class,” she said. “It also leads to toxic rumors regarding certain professors who give out more B’s, since earning one would essentially take you out of the running for most of the Latin honors cutoffs.”

Decker also spoke about her personal experiences adjusting to grade inflation as a prospective law school applicant. She said that she sometimes shied away from taking courses where lower grades were more likely to remain among the higher GPA percentages.

“In conversations with other friends about which language courses they're willing to take at Duke, sometimes they act surprised that I specifically chose to take Mandarin Chinese since it's regarded as one of the more difficult language pathways here,” Decker said.

Cautiousness towards grade inflation is not universal at Duke, however. Senior Erik Dahlberg isn’t too alarmed by the trends.

“It’s something that I haven’t really thought too much about in my classes because the grades that everybody else is getting doesn’t really affect me,” he said. “It doesn’t strike me as something that is necessarily harming the student experience or how much students are learning.”

Dahlberg also isn’t worried about competitiveness when searching for jobs, emphasizing that GPA is only a small component of a job application.

Junior Julian Camacho also agrees that grade inflation is not something he is “too concerned about.”

“It might make things more competitive, but honestly, things are really competitive regardless, and they will be anyway,” he said. “I don’t think my life or death hinges on whether or not this grade inflation will get me or cost me a job.”

Grade inflation, however, may have affected Camacho’s role as a teaching assistant for MATH 122, Laboratory Calculus II with Applications. He noticed that students give him regrade requests for “absolutely everything,” which he believes may be attributable to the increased competitiveness for the highest grades.

Gupta also added that a consequence of increased competitiveness for higher grades may be a disadvantage for students hoping to work in the public sector which “really value hard skills.”

“When everyone around you is … trying to get a good GPA, you avoid those hard skill based classes that will make you stronger in the workforce because you don’t want to sacrifice your numbers,” she said.

Editor’s Note: Gautam Sirdeshmukh, Trinity ‘23, is a former health & science news editor for The Chronicle. Reporting for this story began in spring 2023, when Sirdeshmukh was a senior.

Gautam Sirdeshmukh is a Trinity senior and a staff reporter for the news department. He was previously the health & science news editor of The Chronicle's 117th volume.

Jazper Lu is a Trinity senior and centennial/elections editor for The Chronicle's 120th volume. He was previously managing editor for Volume 119.