When Duke adopted the new mandatory reporting policy regarding sexual misconduct in 2009, it faced backlash from students who viewed it as a threat to confidentiality and the empowerment of victims. It is “not appropriate to make the victims drive the process,” a coordinator of Women’s Center at the time reasoned in The Chronicle, because victims experience “the psychological effects of trauma.” Two years later, in a triumphant Duke Today article, administrators celebrated the apparent success of the new policy, saying that they were “now convinced that [they had] really exposed the problem and empowered the victim.”

The Duke Today article is a quintessential example of the institution’s infantilization of students, antagonism towards advocates, dismissal of constructive criticism, and to be frank, perpetuation of patriarchal defenses. Contrary to administrators’ unqualified optimism at the time, recent research confirms what advocates have been warning all along: that mandatory reporting policies protect universities, not survivors; that little evidence demonstrates the efficacy of such policies; and that they interfere with university teaching and researching by putting faculty in difficult positions.

Looking at history is important because it sheds light on the values and assumptions that have shaped, and maycontinue to drive, administrative decisions. Indeed, Duke’s track record has been so poor that it is unclear how administrators can ever make reparations and restore trust. Perhaps at a more fundamental level, it is simply not in the university’s interest to take advocates seriously because, as Kulbaga and Spencer suggest, institutions in higher education are designed to excuse violence. We should not forget the admonition of my fellow columnist Linda Cao: “the victims of sexual assault are not a flawed exception to our current system; rather, our system is exceptionally flawed.”

This is not to say that there are no good-faith actors at Duke. Nor am I undervaluing the concrete steps that Student Affair is taking by establishing the new GVPI center and heading the SAIL committee. But it is one thing to collaborate with advocates at a topical level, and quite another to unreservedly adhere to the feminist ideals upon which the field of advocacy was founded. In a way, what we have seen are policies of appeasement that barely scratch the surface of what survivors want and advocates demand, that is, optimized survivor control and agency, greater focus on confidentiality, and easy online access to all needed resources.

Moreover, good intentions fall short when staffs and student organizations’ livelihood depends on the very same system that they seek to reform. This fundamental conflict of interest affects not only sexual justice advocates but also those that advocate for racial justice, better mental health services, and students with disabilities. Many chartered organizations face a dilemma: either they work within the system and settle for incremental change, or they protest and jeopardize all of their good work.

The bureaucratic bind is daunting, but we must not concede our ideals. A crucial step is to call for transparency in policy drafting and implementation. Administrators know this demand well, but their attempts at ensuring transparency have been half-hearted and questionable. As a result, they not only sow mistrust but also shun accountability by making procedures impermeable to criticism. For instance, student suggestions are routinely brushed off on the basis that potentially bogus personal anecdotes do not reflect the overall situation, but students have never been granted ready access to relevant statistics that could be used to back themselves up.

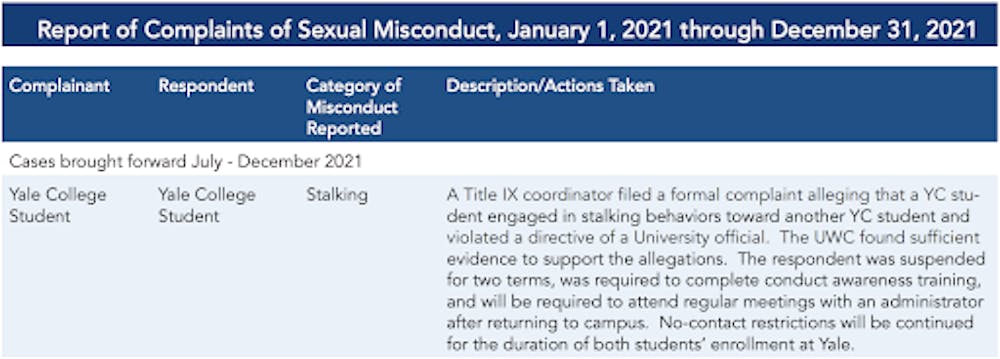

Genuine commitment to transparency requires, for example, that the Office for Institutional Equity release anonymized data about sexual misconduct. This can take the form of reports and case studies that demonstrates how Title IX procedures have been working in practice. Such a report, as Alexandra Brodsky suggests in Sexual Justice, might include concrete examples that “describe the complaint, its outcome, and any reasoning in broad strokes.” It will not only normalize resource seeking and dispel stigma but also give students the opportunity to provide input and advocate for change if they see injustice occuring. Yale University, for example, has been releasing regular reports since 2011, after it faced federal investigation for Title IX violations. These semiannual reports summarize the nature of sexual misconduct complaints and how they were resolved. There is no reason why Duke cannot do the same.

Yale University, August 30, 2022

Student Affairs would be well-advised to maintain open channels of communication with the community. Student leaders tell me that setting up meetings with administrators is such a laborious process that it has become a second job. Even if such meetings are successfully arranged and not cancelled last-minute, they note that the procurement of information is an “individualized effort” that leaves the greater community in the dark. How are students supposed to hold the university accountable with such asymmetry of information?

Institutional critique must go on. Sara Ahmed, who spent her academic career combatting harassment at universities, says this about collective complaints, or rather complaint collectives: “we sound louder when we are heard together; we are louder.” I invite you, the reader, to respond to this call. I also urge the administrators to take our critique seriously. Our community has suffered the consequences of institutional ineptitude for far too long, and now is not the time for administrators to lapse into defensiveness and passive-aggression.

Billy Cao is a second-year at Trinity. His columns run on alternate Fridays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.