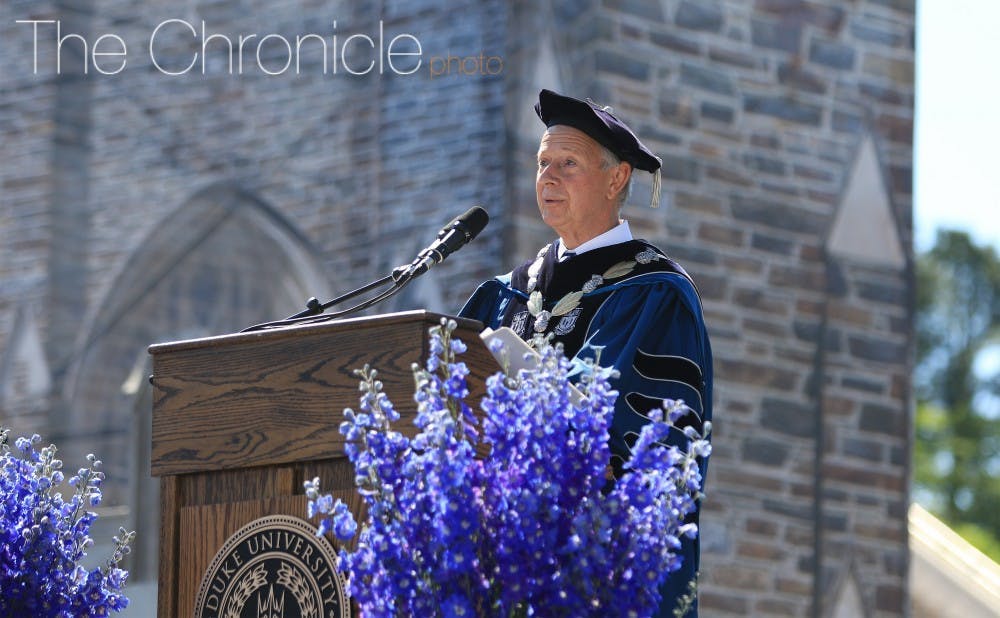

In August 2018, Richard Brodhead, president emeritus of Duke and honorary chancellor of Duke Kunshan University, delivered an address to DKU’s inaugural class, introducing the project’s origins and the importance of founding a joint-venture university in China.

Outlining the five key partners that created DKU—China, Duke, the city of Kunshan, Wuhan University and students—Brodhead spoke on the history of liberal arts education and the impact DKU’s first class would have on the school’s character and habit.

Now retired, he will address DKU’s Class of 2022 Commencement on May 20, in a hybrid ceremony held at Duke and DKU.

Duke Kunshan Report editor, Charlie Colasurdo, asked Brodhead about his involvement with DKU, what he plans to say to its inaugural class and where he sees the project going next.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Chronicle: In your speech to DKU’s inaugural class in 2018, you described the complex process by which DKU’s undergraduate program came to fruition, particularly with the Academic Council and Board of Trustees’ approval of issuing Duke degrees to its graduates. With the first class of Duke degree-receiving DKU students about to graduate, what do you think about that decision, and its impact on the Duke community?

Richard Brodhead: To me, it’s very interesting. Not every international venture had the same degree of very thoughtful faculty and trustee engagement that happened at Duke, and that always struck me as very important in regards to the degree of ‘buy-in’ of Duke’s participation in DKU. People used to say, “Oh, what are you going to do, create a campus in every major city in the world?” Well no, because this was never about setting up franchises, this is not KFC. I think people understood the risks of it, they understood the promise of it. At the end of the discussion, people looked at each other and the idea was, “Yes, we’ve asked every question, we’ve thought this through very well, some people opposed it and many people supported it, and forward it went.”

TC: You were recently quoted as saying “DKU remains one of the most important international educational experiments in modern times.” How do you judge this experiment in the context of your experience leading Duke and Yale University? Is DKU a viable and replicable model for the future of international education?

RB: I don’t know whether it is [replicable] or not, but the history of education is the history of replications, replications with variation. Harvard was founded by people nostalgic for Cambridge, Tsinghua [University] was founded on an American model, there’s always a degree of models being imported and then adapted. For me, what became clearer and clearer and what was very persuasive to the Duke faculty that participated in this, is that the fact that it’s in China is only one salient fact about DKU. The other is its model of pedagogy, that it brings the model of active, open-ended inquiry to a country that’s very hungry for it. Every American university still does majors within departments, but departments are an increasingly antiquated intellectual structure, with a long iron hand on the present. The first couple of years before the [pandemic] gave the feeling that this was working as well or better than we could have hoped. Faculty who weren't Chinese scholars who went and taught there were just amazed by how interesting the experience was—of having to rethink everything they taught at Duke from the point of view of students, where you couldn’t take the same things for granted.

TC: What about DKU are you most proud of?

RB: What I’m most proud of is that it exists. No one knows the number of little obstacles that had to be overcome and things you had to get right for it to ever open its doors. That’s fine—who knows how Duke was created? It’s a lot of work, a lot of challenges, a lot of imagination, and when it’s done, you’ve got the products so you don’t need to worry so much about the process anymore. What I’m proud of is that DKU was about an ideal of what possible cross-cultural education could look like. Bringing a model that wasn’t just bringing Duke to China—it was like we were using the occasion of China to reinvent undergraduate education, for both Duke and China.

TC: Did you harbor doubts about the program’s success once you stepped down as Duke’s president? How did you ensure Duke kept up its commitments to the DKU project?

RB: The nature of a project like this—you said it was a complicated process of getting approval—and indeed it was. That’s because this is a complicated thing we’re trying to do, and also, we were not trying to do it for one year, or five years. Universities are for a generation, they’re for the long term. You had to put all the work into it for the long term, although your first results were in the short term. The degree of thoughtful planning was, in my measure, extraordinary. I feel when I go [to Duke], I still feel how seriously Duke takes DKU, how committed they are to playing their part in it. Look at the welcoming of [DKU] students to campus.

TC: DKU was the first of Duke’s schools to face COVID-19, and has spent much of the last two years on a changed campus, with international students unable to return to China. Conversely, it allowed for a greater level of intermingling with Duke’s student body, with DKU students of all years studying abroad in Durham. What do you think about these unexpected outcomes and how they’ll shape Duke’s relationship with DKU?

RB: When you plan for something, you had probably better plan for unexpected outcomes. Generals say: “Your battle plan is good until the first shot is fired.” As history unfolds, it presents all the challenges you anticipated, and it’s certain to present challenges you didn’t anticipate. That has come true in spades with DKU. Obviously, we’re full of regret about the parts of the original vision that haven't come perfectly true during this time because of COVID, but everybody in the world has been living with this fact. It all becomes a question of adaptation, how imaginatively can one adapt, how much can you keep in mind the goals you had. Your goals weren’t the circumstances—our goal was not to have things go well. Our goal was to have an educational program, and in good times it would work one way, and then in other times you’d have to use your wits.

TC: What role do you see DKU playing within both higher education and Duke?

RB: Duke is a much less insular university today because it has had this deep China involvement. China is not going to be irrelevant to the future, so a university that now has more faculty, pays more attention, has more contact, that’s a good thing for Duke in any possible world.

As for the graduates of DKU, I’ve gotten to know a lot of people in China and Chinese education through my years of visiting over there. They understand that the kind of student that can come out of a program like [DKU] is uniquely valuable because they’re not narrowly trained. They look at the world as a scene for their active involvement, they are used to working in teams, they’re used to solving problems that didn’t exist when they went to college. That’s the upside. Could something bad happen—could DKU be closed? Of course it could, we all know that. But it wouldn’t be my hope.

TC: You’re addressing international students from the inaugural class in-person, at Duke, next week. It’s a much different first commencement than anyone could have envisioned back in 2018—how are you planning on recognizing this in your speech to the graduates?

RB: Anybody who thinks that what happened at DKU in its first few years is uniquely horrible in history doesn't know much about the history of higher education. So I tell some of their stories, and the other thing I talk about is how having your plans dashed and having to, on the stop, quickly revise them, is itself a powerful form of education.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Charlie Colasurdo is Kunshan Report editor and a senior in the second graduating class of the Duke Kunshan campus’s undergraduate program, located outside Shanghai, China.