Look around Durham today, and you’ll see neighborhoods like Walltown, Trinity Heights and Hickstown, as well as the Durham Freeway that cuts diagonally through the city. These houses and highways have existed for decades, but few know the full story behind them.

The communities and infrastructure of Durham are products of the city's 152-year history. This city endured the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, experienced tobacco and textile booms and became an economic and cultural hub in North Carolina. Throughout this tumultuous history, Durham’s housing landscape evolved as people moved into the city.

In 2019, a group of researchers from Duke and Durham known as Bull City 150 created an exhibition on Durham’s housing history called Uneven Ground. It debuted as a celebration of the 150th anniversary of Durham’s founding as a physical exhibition in Classroom Building on East Campus. Using maps, photographs, official documents and Durhamites’ personal stories, the exhibit tells the story of Durham’s legacy of systemic racism in housing from colonial America to the 1960s.

“We went through a lot of revisions of this [Uneven Ground] script,” said Tim Stallmann, research cartographer for Bull City 150. “What we were trying to do was tell more of a structural history than is often told in Durham.”

Robert Korstad, faculty director of Bull City 150, believes that Uneven Ground has the power to change how the Durham community sees the city—and what actions they’re willing to take to improve it.

“Unless we educate people about the kind of structures of inequality that exist in our society and on a real local sense here, we're not going to make very much progress in terms of developing public policies,” he said.

Beginnings

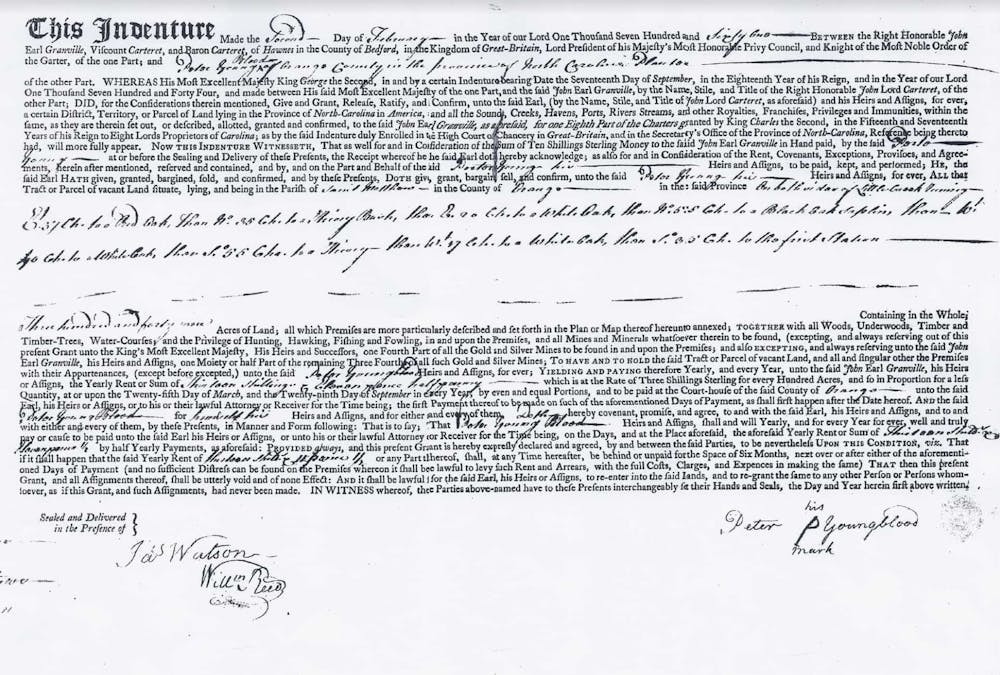

Durham’s story began in the 16th century, when the land was home to the Eno and Occoneechee people. In the mid-18th century, British colonists arrived and called the area and its surrounding land the Carolina colony, displacing the tribes who were already there, according to the Uneven Ground exhibit.

In 1849, Bartlett Snipes Durham, the city’s namesake, provided land for a new station on the newly-chartered North Carolina Railroad route. Durham city’s official birthdate is April 26, 1853, but the town wasn’t incorporated until April 10, 1869. Durham County was formed on April 17, 1881 from portions of land transferred to the county by Wake and Orange Counties.

Large plantations such as Hardscrabble, Cameron and Leigh had already been established before Durham’s founding. At the start of the Civil War, nearly one-third of people in Orange and Durham Counties were enslaved.

When enslaved Black people were declared free by the Emancipation Proclamation, they had no means to buy land. Poorer white people had also never owned land.

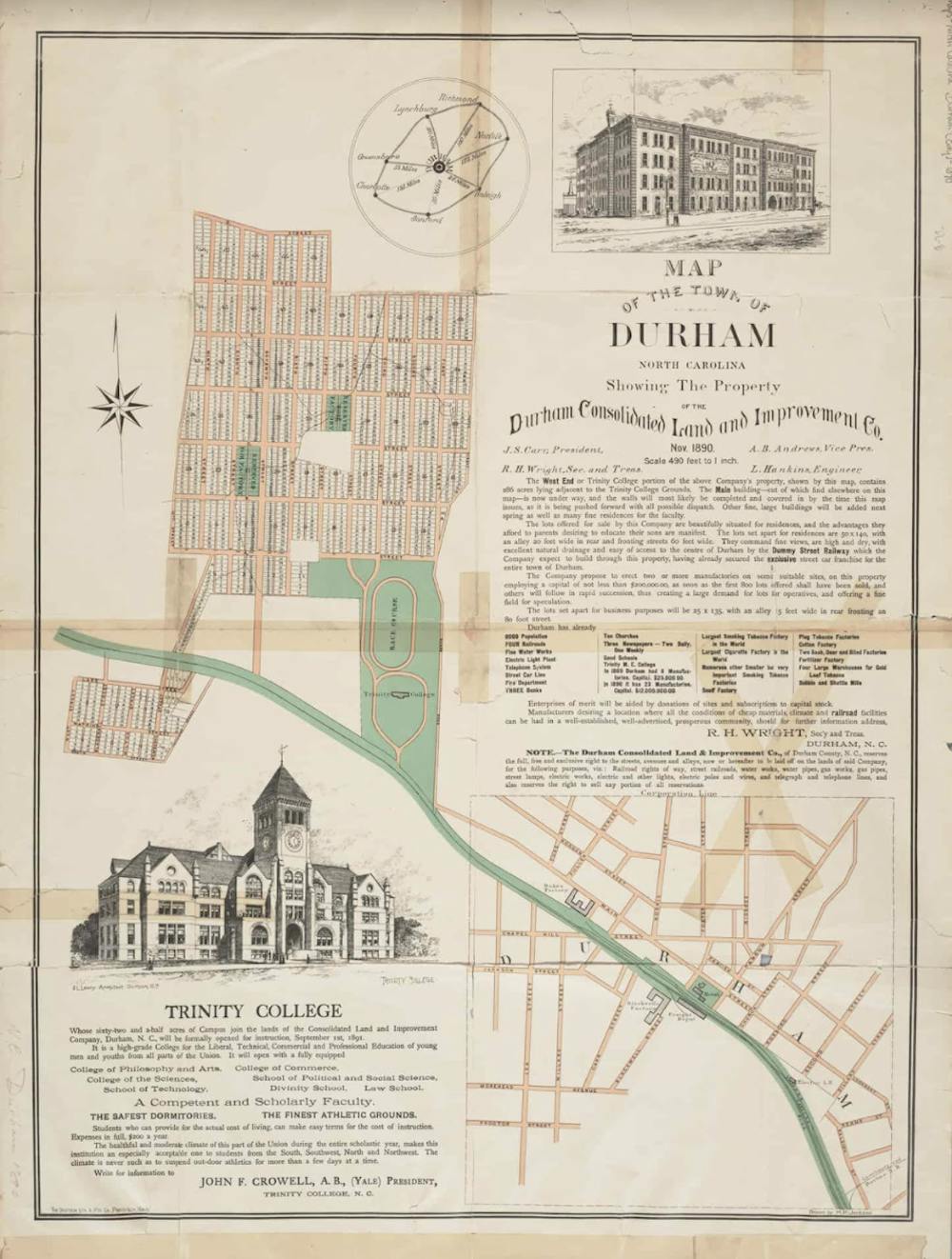

While the Black and white farmers became sharecroppers and struggled to own land, Durham’s industrial elite owned the majority of premium land. This included the Duke family, who had built one of the largest tobacco empires in the word. They invested in residential real estate and in Trinity College, later named Duke University.

By the turn of the century, many real estate speculators had invested in tracts of land around the city as well. The Durham Consolidated Land and Improvement Company, one of Durham’s largest real estate companies, purchased nearly 300 acres in what is now Trinity Heights and Walltown neighborhoods.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Working class Durhamites

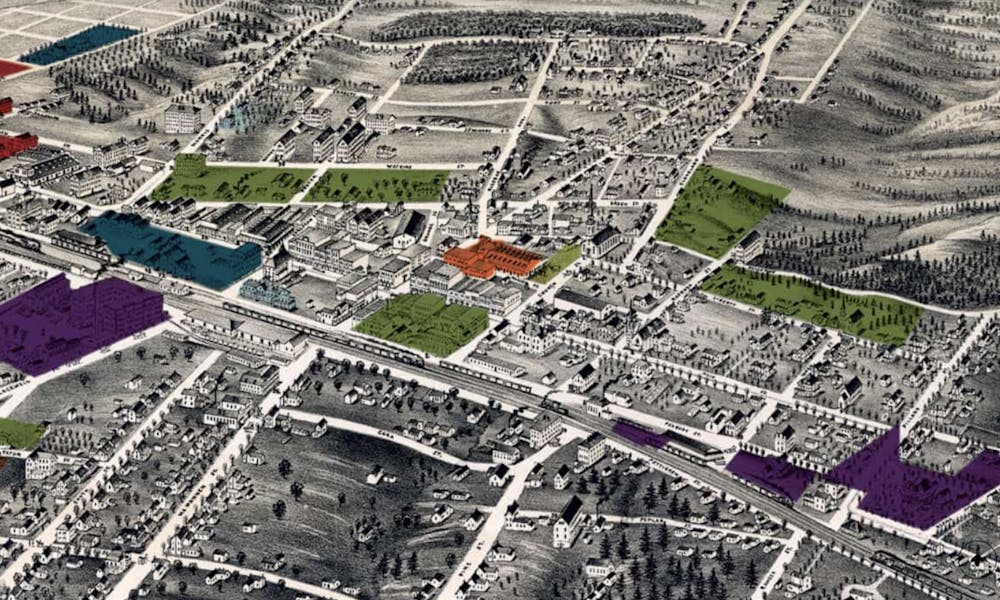

As Jim Crow laws spread throughout the South in the 1890s, Durham became a key destination for Black rural migrants, who moved into Durham’s apartments and worked primarily in the booming tobacco industry, according to the Uneven Ground exhibit.

According to Korstad, Durham’s textile industry rose to prominence as people looked for ways to create new economic opportunities to rebuild the South after the Civil War. However, the textile mills employed almost entirely white workers. Working-class white workers lived in cheap subsidized housing from their employers and settled around textile mills.

“To some extent, the way this racial segregation was solidified was when the textile mills started growing up Durham and all around the South, manufactures built housing for their workers,” Korstad said.

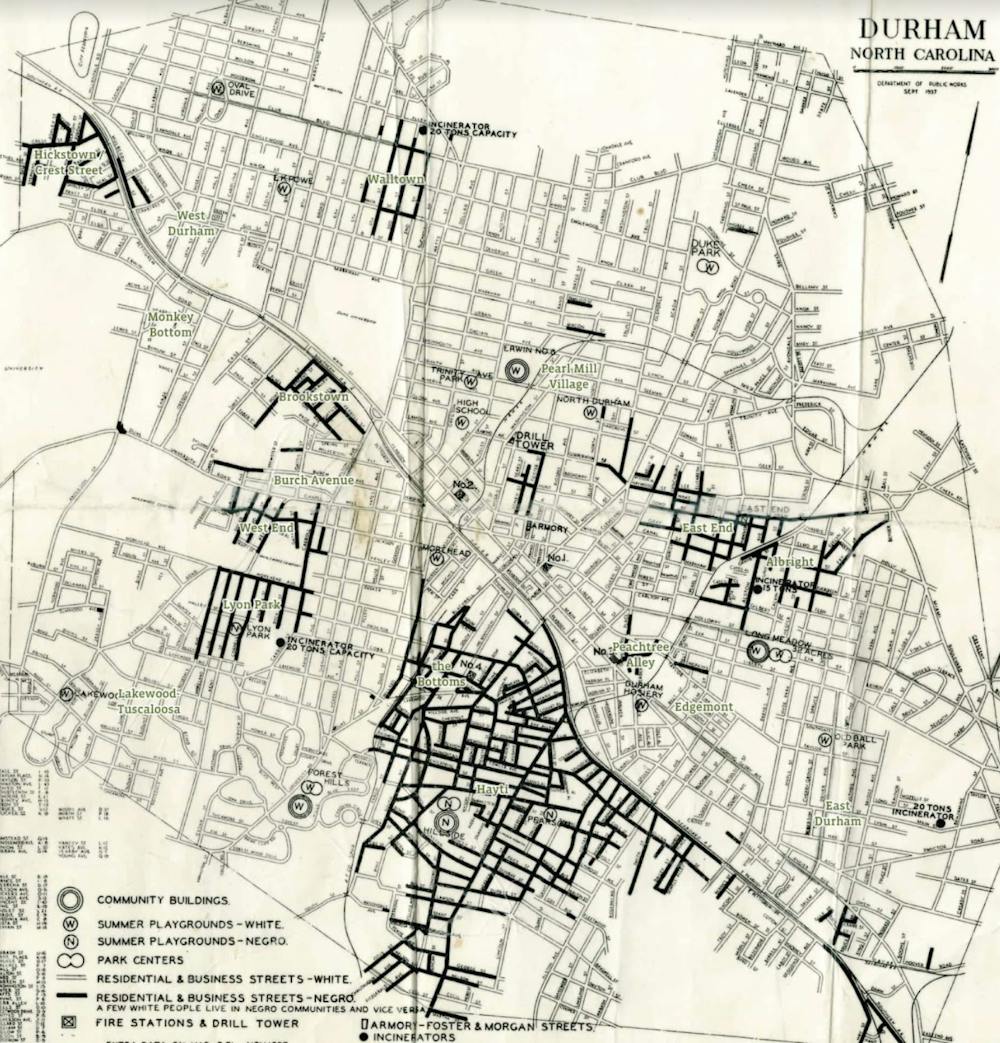

Employers didn’t provide housing to their employees, most of whom were Black and settled in five main areas: Hickstown, Walltown, West End, East End and Hayti. Hayti was the largest area, where more than half of Black Durhamites lived.

“Over time, Durham becomes a series of neighborhoods which are pretty strictly segregated by race, but also by social status and income. Some of the way [these neighborhoods] get set up by 1900 is to some extent the way they look today,” Korstad said.

Working-class Black residents faced some of the worst housing conditions in Durham. Their neighborhoods contained more garbage incinerators and unpaved roads than white neighborhoods. Sewer lines were also installed later in Black neighborhoods than in white neighborhoods. These conditions discouraged investment and led to poor health for Black residents.

Still, the neighborhoods were close-knit. Hayti became a destination for Black activists, entertainers and academics, connecting Black Durham to broader cultural and political movements.

Over time, Hayti became a “distinct kind of racially segregated community,” Korstad said.

“The Black schools were placed there, which kind of helps solidify that,” he said. “The Black middle class emerged in the late 19th century and developed the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance.”

Stella Adams, CEO of S J Adams Consulting, a firm that supports fair housing, said that Hayti’s community leaders were self-reliant and made significant contributions to Durham’s economy.

“They were not dependent on the white community for much because they were able to create their own society,” Adams said.

Land ownership was a mark of status and security. Institutions like NC Mutual helped Black people become homeowners when white institutions refused to lend to them. Three out of four underwritten mortgages from Black banks were held by NC Mutual.

Maintaining housing segregation

Even with institutions like NC Mutual, housing segregation persisted into the 20th century. Individual prejudice, private industry and government laws built “invisible walls” to maintain segregated housing in Durham, according to the Uneven Ground exhibit.

These implicit forms of segregation included deed restrictions, suburban development, zoning laws, steering, real estate marketing, redlining and public housing. Together, they led to racial gaps in home ownership, wealth, security and mobility.

A 1926 deed from Hope Valley declared that “each dwelling so constructed shall cost no less than $7500,” making it impossible for working-class people to afford the homes. Black people were also not allowed to live in the community except as domestic workers.

Steering was an official practice in the real estate industry and very common in Durham. Real estate agents guided home buyers toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on the buyers’ race.

“A realtor should never be instrumental in introducing a neighborhood … members of any race or nationality…whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood,” read a 1924 Code of Ethics from the National Association of Real Estate Board.

In 1937, knowing that planting trees could raise the value of property, the Durham city council led an effort to plant trees between sidewalks and city streets, Adams said. However, they did not plant trees in Black neighborhoods.

“Things that don't seem important at the time became important over time [and] created some of the inequality that exists,” Adams said. “Who would think that the planting of trees would make such a difference in the evaluation and critique of neighborhoods?”

Urban Renewal

In the late 1950s, the Urban Renewal movement spread across the United States. Its purpose was to build interstate highways that connected cities to suburbs. The federal government also gave cities billions of dollars to tear down blighted areas and replace them with affordable housing.

“There was this realization that in many of these urban areas, there were large parts of them where the housing was really substandard, particularly in African American neighborhoods,” Korstad said.

Eager to receive large amounts of money from the federal government, Durham’s city government made three big promises to the Black community: new housing, new commercial development and major infrastructure improvements in Black neighborhoods.

Most working-class Black people did not know anything about Urban Renewal, but over 90% voted to support it in a bloc with what is now the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People.

In the end, the only results of Urban Renewal in Durham were broken promises. Hayti’s business district was primarily dismantled in order to build the Durham Freeway. Over 4,000 families and 500 businesses were displaced.

“Unfortunately, there was a lot of money for tearing things down, but there wasn't a lot of money to build things back up,” Korstad said. “There was virtually no urban renewal.”

In the 1960s, tenants mobilized to fight for better housing by forming organizations such as

United Organizations for Community Improvement and Operation Breakthrough. They believed residents in every poor Black and white Durham neighborhood deserved a say in the decisions that affected them.

Korstad is unsure what happened to the people who were displaced in Hayti. “What we’re guessing is a lot of Black families started moving into formerly-low-income white neighborhoods, particularly in East Durham,” he said.

Adams says the displaced communities in Hayti built an area called Tin City on Fayetteville Street.

“We hold on to the Fayetteville Street corridor … from Fayetteville Street when you get off the interstate, down towards Central, that's pretty much all that remains of the vibrant, bustling city that was destroyed by Urban Renewal,” Adams said.

Durham today

Today, Durham faces a gentrification crisis—increasing property values have been attracting wealthier people to the area and raising property taxes.

The median sale price for homes sold in Durham increased by over 50% between mid-2010 and October 2019.

“People get pushed out because they can't afford to live there anymore,” Stallmann said. “There's a lot of neighborhoods, historically Black neighborhoods that are facing pretty rapid gentrification.”

Bill Bell, mayor of Durham from 2001 to 2017, said that he and his team worked to establish mixed income housing in areas that were “particularly distressed for long periods of time,” including a spot near Eastway Elementary School and in Rolling Hills.

“While we didn't do as much as we would have liked to address the affordable housing issue, that doesn't mean we weren’t looking at it, or some things weren't done,” Bell said.

Durham also faces an eviction crisis. After the Supreme Court declared a Biden administration eviction moratorium unconstitutional at the end of August, landlords have begun to evict tenants for not paying rent.

Many tenants have no means to pay their rent due to unemployment caused by the pandemic, Stallman said. A statement about their eviction remains on their permanent tenant record. Children sometimes have to switch schools, hindering their learning.

“There's this whole mix of dynamics that are happening right now [regarding Durham’s housing situation],” Stallmann said. “It's definitely coming to a pretty heated situation.”

Katie Tan is a Trinity senior and digital strategy director of The Chronicle's 119th volume. She was previously managing editor for Volume 118.