The next time you head to class on Davison Quad, there’s a good chance you’ll be greeted by an exhibit commemorating one of the first five Black undergraduates to attend Duke.

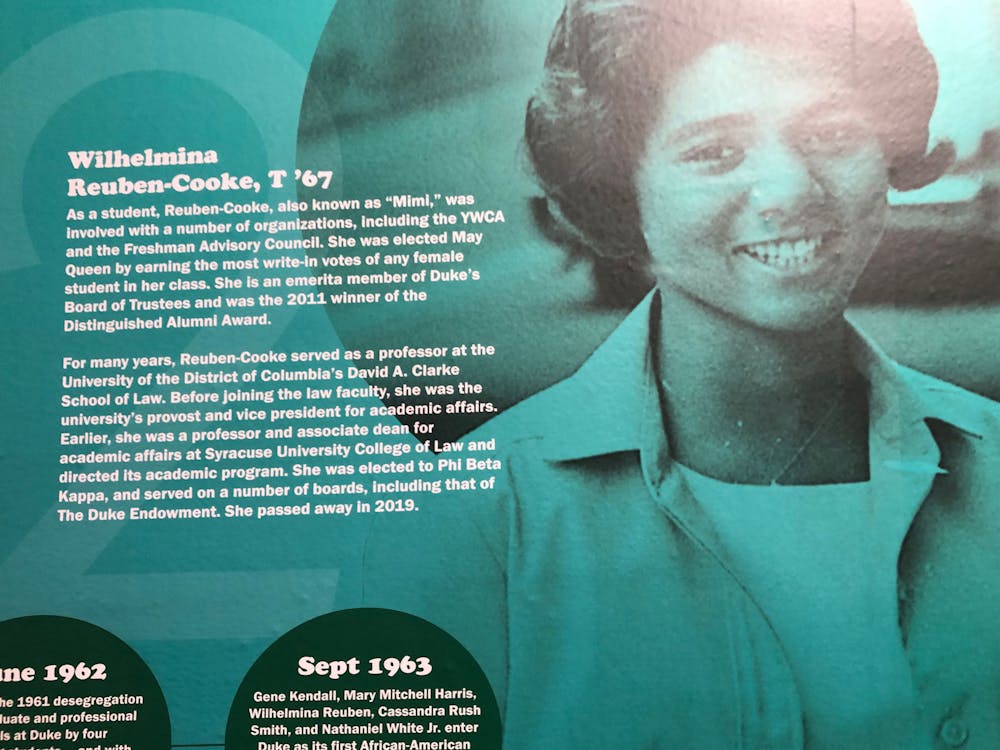

Duke hosted a dedication ceremony for the Reuben-Cooke Building—named for Wilhelmina Reuben-Cooke, Women's College ‘67—Friday evening. The decision to rename the Sociology-Psychology Building after Reuben-Cooke was announced in September 2020. She is the first Black woman to have a building at Duke named after her.

While at Duke, Reuben-Cooke was a civil rights organizer and a member of Phi Beta Kappa, a national undergraduate honor society. She went on to become an attorney, arguing before the Supreme Court, testifying in Congress and serving in higher education at Syracuse University and the University of the District of Columbia. She also served on the Board of Trustees from 1989 to 2001 and was a trustee of the Duke Endowment until her passing in 2019.

The ceremony began with a prayer led by Luke Powery, associate professor of homiletics and dean of Duke Chapel, who celebrated Reuben-Cooke’s “luminous legacy.”

“May those who enter this building in her name be refreshed in mind, body and spirit,” Powery said.

President Vincent Price acknowledged the presence of Reuben-Cooke’s family—including her daughters, siblings and her husband, Ed—as well as other members of the First Five and their relatives. Representatives from the Board of Trustees, the Duke Endowment and other universities were also present.

Price said the commemoration was one of few events in daily University life that could truly be called “historic.”

“As we gather here on Davison Quad to perform two relatively simple acts—formally naming a building and unveiling a portrait—there is meaning behind what we’re doing here,” Price said. “For four decades after this building opened, only white students could take classes here. That changed in 1963.”

Ed Cooke became emotional as he described his late wife, saying that she only stood 5 foot 6 inches but carried herself as if she were six feet tall.

“Early in our marriage, I came to realize I was not destined to win many fights. She responded to the tone and content of a then unwise attempt on my part to change her behavior with ‘I am not one of your airmen,’” Cooke said, referencing his enlistment in the Air Force.

Cooke said that Reuben-Cooke’s bond with the other members of the First Five “ran deeper than we might perceive,” and that they often recalled the fear, challenges, fun and camaraderie that came with their tenure at Duke.

Cooke also described Reuben-Cooke’s life philosophy and how she was most interested in fostering environments where people loved and respected one another. He pointed to a paper by attorney and judge Harry T. Edwards that contained three lessons Reuben-Cooke would’ve adhered to—to not feel entitled to something one did not work for, to never work for money and to not be afraid of taking risks or accepting criticism in the pursuit of goodness. His speech was met with a standing ovation.

Lucy Reuben said Reuben-Cooke was deeply rooted in the family history and culture, and became the “sister-mother” of the family as she was the eldest of her siblings and cousins.

“Wilhelmina reflected the unflappable poise and acuity of our mother, the gentle charm and affability of our father and the steely perseverance of both parents,” Reuben said.

Reuben-Cooke’s father was Rev. Odell “O.R.” Reuben, the first African American to earn a doctoral degree from the Duke Divinity School. Lucy Reuben said that when Reuben-Cooke neared college age, Duke officials and Waldo Beach, professor of Christian ethics, approached O.R. Reuben to inquire about her attending. This led to Reuben-Cooke being the only member of the First Five who was not from North Carolina, Lucy Reuben said.

Reuben also recounted a memory in which Reuben-Cooke saw a monument at Morris College, where their father was president, and repeated the words: “We have done our best.”

“Wilhelmina Matilda Reuben-Cooke, you have done your best,” Reuben said. “May each of us live from this day forward so that, like [Reuben-Cooke], each of us can one day say ‘I have done my best.’”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Gene Kendall, a member of the First Five, confessed that he had written a speech and decided shortly before the ceremony that it “was no good anyway.” Instead, he opted to “share a lifetime of remembrance” about Reuben-Cooke. Whereas she was the eldest among her biological relatives, with her Duke family, she was the little sister.

“Mimi was the superstar among us,” Kendall said. “She didn’t tell us. We knew.”

Reuben-Cooke reflected the idea that “what you would like to have on your tombstone should be reflected in how you actually live,” Kendall said.

Duke Endowment Chair Minor Shaw said the Endowment was grateful to have known and worked with Reuben-Cooke, and that the dedication was meaningful to those privileged to share her life and to the people who had yet to be inspired by her.

Board of Trustees Chair Laurene Sperling called the dedication a “historically-fitting recognition,” and said Reuben-Cooke’s legacy was “towering.”

The building contains a portrait of Reuben-Cooke painted by Detroit-based artist Mario Moore, as well as a permanent history exhibit designed by Tobias Rose of Kompleks Creative and Meg Brown, the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation exhibits librarian, among others.

Earlier this month, the bronze plaques outside of West Campus buildings were replaced with aluminum signs, including a new sign for the Reuben-Cooke Building.

Note: This article has been updated to reflect that Reuben-Cooke graduated from the Women's College, not Trinity College of Arts and Sciences.

Nadia Bey, Trinity '23, was managing editor for The Chronicle's 117th volume and digital strategy director for Volume 118.