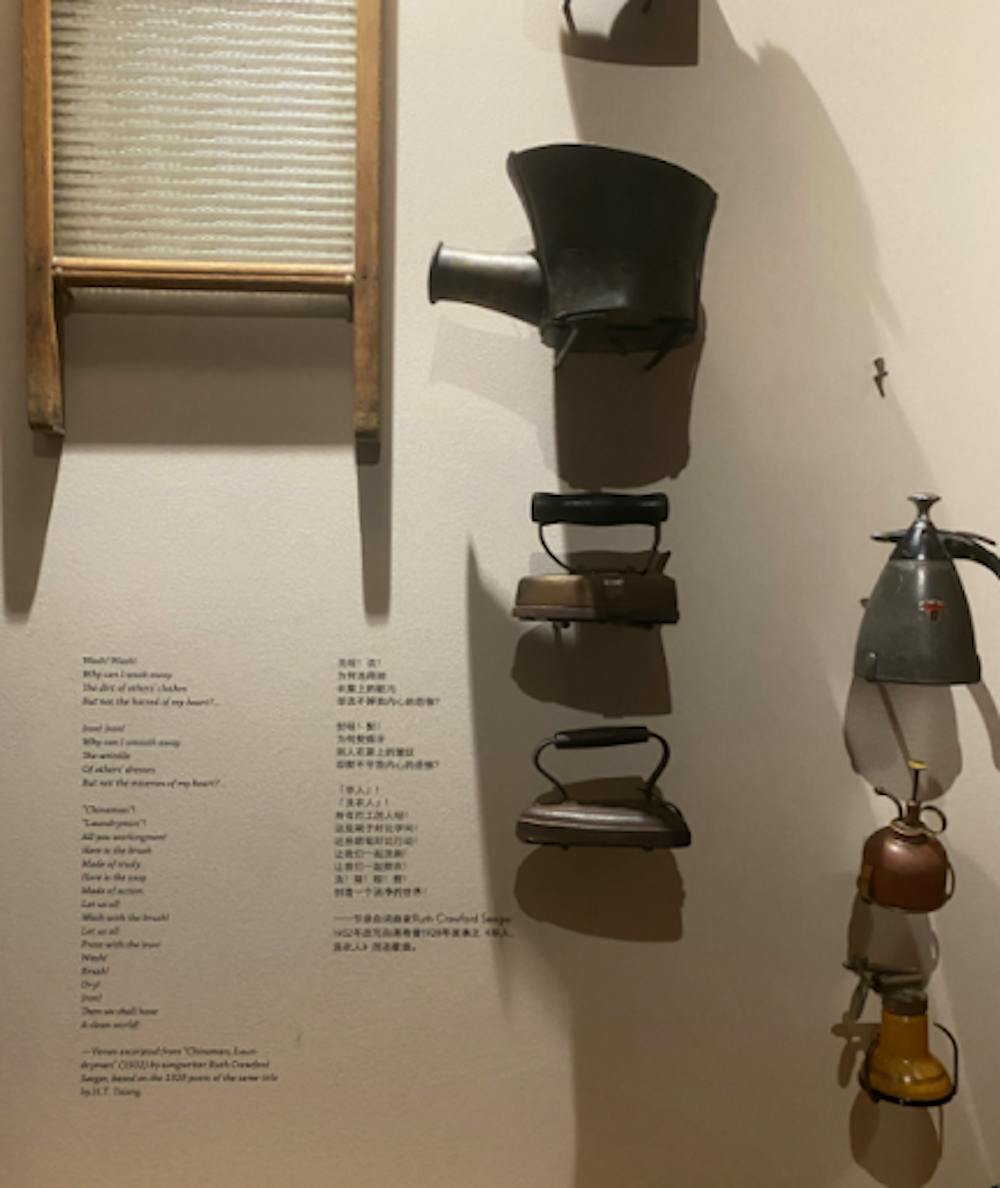

Wash! Wash!

Why can I wash away

The dirt of others’ clothes

But not the hatred of my heart?...

Iron! Iron! Why can I smooth away

The wrinkle

Of others’ dresses

But not the miseries of my heart?...

“Chinaman”!

“Laundryman”!

All you workingmen!

Here is the brush

Made of study.

Here is the soap

Made of action.

Let us all

Wash with the brush!

Let us all

Press with the iron!

Wash!

Brush!

Dry!

Iron!

Then we shall have

A clean world!

Words scatter across the walls (as they do, in museums). These lyrics from “Chinaman, Laundryman,” based on a poem by H.T. Tiang, are printed neatly on a white wall displaying irons, steamers, and an old washboard. Anyone familiar with Chinese-American history will immediately understand the significance of these objects, especially given their location at the entrance of the Go East! Go West! exhibit in the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA). Another poem is printed on the exhibit’s translucent sign, above gray patterns of ocean waves.

This stood out to me the most: the sheer amount of text in this building. Yes, there are artifacts, posters, screens and decorations. There are testimonial transcripts and interview videos looping in the background. But first and foremost, the visitor will see and hear: words.

The main exhibit, installed this past July, is titled: “Responses: Asian American Voices Resisting the Tides of Racism.” In a nondescript rectangular room, papers are painted into different shades of gray, with inky black text. The pages created a timeline encircling the whole space, on all four walls, spreading from the arrival of Chinamen to Californian shores amidst gold-mining and railroad-building, till 2020, during the surge of anti-Asian hate crimes in a global pandemic. As documented in Tiang’s poem, hatred and suffering are not new at all.

American concepts of Chinese culture have always been attached to a Western superiority complex. We (Americans including myself) fetishize and exoticize the “Oriental,” we see these strangers from a different shore as the constant “other,” and their living we see simply as art: dainty, beautiful, stereotypical, something to collect, like an artifact. From the invention of chop suey, to Anna May Wong’s Hollywood career, to people walking around today with nonsensical Chinese characters tattooed across their skin -- the “Oriental” has always been something aesthetic, to admire, and simultaneously, something to hate and fear.

So we (Asians including myself) use words to overpower the fear. Words to claim our space in the world today. Words to remember the indignities suffered by our own forefathers and mothers. Words to express not only the beauty of this culture, but the humanity of it, too. Mandarin, at its roots, is hugely different from English. This language barrier only increased the “otherness” felt and now unquestioningly accepted between China and America today. MOCA’s use of both English and Chinese placards in its flowing, cyclical exhibits are not only practical for the visitors, but serve as a reminder: we can all read this. Two languages, one story. It’s always just been one story.

More importantly is the realization that despite history being one story, there exist multiple perspectives, and there will always be multiple perspectives. Even the well-meaning slogan “YELLOW PERIL SUPPORTS BLACK POWER,” which is used in posters in photographs in Responses has created controversy due to its implications of Asians identifying as yellow, or indirect equating of Asian discrimination and Black struggles for equality. Any words we speak today inevitably carry the weight of its historical use also.

In the dimly-lit galleries of MOCA, sudden gratitude dawned upon me as I recalled a seminar on Asian American literature I took senior year of high school, titled “Strangers from a Different Shore.” It was during this class that I first learned of Anna May Wong and Vincent Chin, and where I read incredible literature (including The Buddha in the Attic, The Fortunes, Interpreter of Maladies, and Yellow, now my favorite collection of short stories). Looking back, I appreciate how special this opportunity was: to be educated on literature written in Asian voices rather than the Eurocentric, Anglo-American texts in American high schools.

But disillusionment followed when I realized students who registered for “Strangers from a Different Shore” are people already seeking out marginalized voices. My grade was roughly 85% white; meanwhile less than half this class was white. As a friend complained because the class wasn’t taught by an identifying Asian, I remember feeling oddly pleased the teacher was a white male. See, I thought to myself, non-Asians care about Asian literature too!

But most men are not like my teacher (he’s awesome). The majority of students are not like the ones who took this class. Everyone in that space was already respectful of and comparatively well-educated on Asian American history and literature. Likewise, in New York, those who do not know nor wish to know the experiences of Chinese in America are the ones who will stride right past its doors on Centre Street, and continue living with their single perspective. Those who need to hear these different voices most, may never enter the spaces to hear them.

As I learned after my visit to MOCA, those who try to lift up the voices may not be presenting all perspectives either. Despite claiming to present Asian American “responses,” MOCA has still tuned themselves to please outsiders. Just earlier this summer, MOCA catered towards New York City’s elitist expectations against the wishes of the Asian community. Jonathan Chu, co-chair of MOCA and mega-landlord, accepted Mayor de Blasio’s bribe of $35 million to support the city’s proposal for building a new detention center in the area. Members of the community boycotted MOCA’s acceptance of the $35 million with the slogan “Chinatown is not for sale.” The irony is clear: the voices of protest are going unheard within MOCA, a museum that promotes the displacement and gentrification of the very people whose culture it means to represent.

Personally, I heard other silenced voices as well. As a Taiwanese-American wandering through the exhibits, I found myself searching for any mention of Taiwan. There were none. Why? Were the minds behind these exhibits pro-Taiwanese-independence, and therefore left Taiwan out of this “Chinese” museum? Or was this politically tense island intentionally forgotten?

Having walked past, a few weeks ago, a building with the sign (in Chinese): “The Republic of China’s American Branch” in Manhattan’s Chinatown, I know that the PRC and ROC are still struggling against each other in America. Taiwan is far from irrelevant to New York City. Madame Chiang Kai-shek herself actually stayed in a high-rise on the Upper East Side. Perhaps the history is too complicated to fit onto MOCA’s curated walls. But it makes me wonder: what else — or who else — do institutions claiming to exhibit us, exclude?

I hope that someday, light can be shed on these stories, for visitors to contemplate and understand. I hope that somehow, the walls can expand, brimming with space, to the point of bursting — and instead of labels, texts, and exhibits, you see the community outside. These unheard perspectives await; you have to be willing to listen. Then instead of silence, there can be discussion, acknowledgement, and sharing. “Then we shall have/ A clean world!”

Jocelyn Chin is a Trinity sophomore. Her column runs on alternate Wednesdays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Jocelyn Chin is a Trinity senior and was an opinion managing editor of The Chronicle's 118th volume.