Most fans of online quizzes are familiar with the Pooh Pathology Test: each character of the classic Disney franchise embodies a different psychiatric diagnosis, and users can answer a series of questions to see which character they relate to the most. I was never a huge fan of the Hundred Acre crew, but I was still fascinated by the use of children’s cartoon characters to describe mental health conditions. Recently, I realized that this trend was not exclusive to Pooh and his friends — it could also be attributed to the characters in my favorite Pixar movie: “Finding Nemo.”

Being one of the only movies my brother and I could agree on, our family’s “Finding Nemo” DVD became scratched beyond use over the course of my childhood. I loved the variety of high-strung and laid-back marine characters, their action-packed adventure, the Rat Pack soundtrack and of course, the bold colors and textures characteristic of Pixar. It wasn’t until I was in college, however, that I truly appreciated the film’s portrayal of disability.

Nemo and Gill both have physical disabilities, with Nemo’s “lucky fin” and Gill’s torn one, but the film especially seems to emphasize — and even celebrate — the mental differences of its characters.

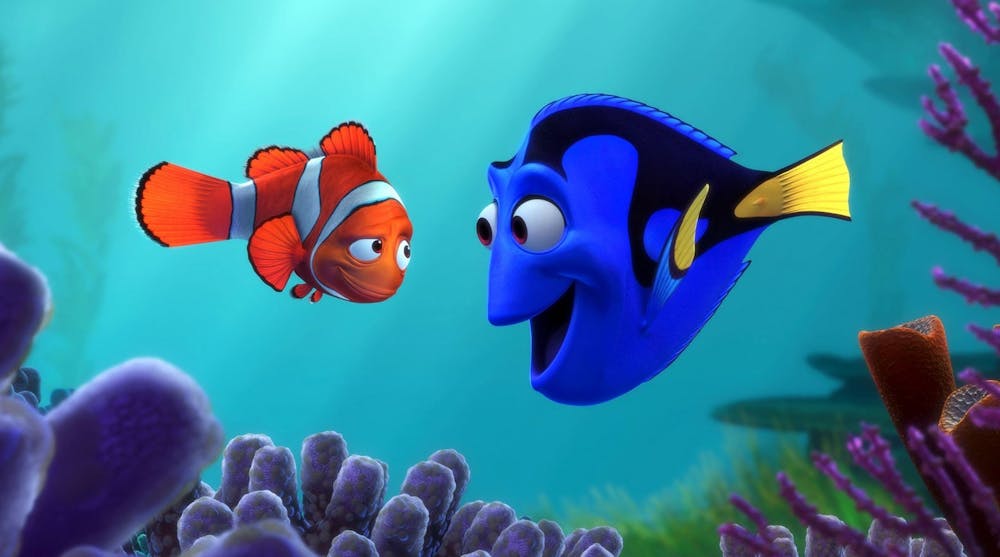

After Marlin’s wife and kids were killed by a barracuda, he displays the constant worry and distrust associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). His lone surviving son, Nemo, also displays some symptoms of anxiety. Side characters Jacques and Gurgle display the obsession with cleanliness often linked with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD); the vibrant royal blue Deb has multiple personalities; and Bruce and the sharks battle their fish-eating addiction at AA-style meetings.

And then there’s Dory, the iconic blue tang that made her way into our homes and hearts with short-term memory loss and a hopeful mantra to “just keep swimming.” She most explicitly suffers from her amnesia but also displays the often-unspoken positive side of neurodiverse brains. Although Dory has trouble remembering recent conversations, she remembers Nemo’s “P. Sherman” location and is the only fish that can read — similar to how many individuals with autism are incredibly skilled in a specific area, or people with ADD can hyperfocus on something they’re interested in.

One of the biggest controversies surrounding neurodivergence is the idea of “curing” it. Some have posited that the alternative way of thinking associated with ADHD, for example, can actually provide benefits to creativity and problem-solving skills. Yet, when school and work demand time management skills often inhibited by this disorder, people diagnosed with it may want nothing more than to feel neurotypical — to feel “cured.” But in this 2003 children’s film, no one tries to stop or change or “fix” the characters or their behaviors. They work with them —and each other — and they succeed.

Dory’s memory loss is frustrating to Marlin, but they stick by each other regardless. Likewise, Marlin’s past trauma exacerbates his anger, but Dory consistently provides comfort and companionship. Ultimately, their mission is to, well, find Nemo, and their inner differences are just side challenges inevitably faced along their journey that allow them to grow closer. As cliche as it sounds to praise a Pixar movie for highlighting the strength in our differences, it teaches kids that many of these characteristics are just that — not illnesses to be cured, but differences to be understood and naturally accepted.

As a kid, they were just funny characters. And that could be all they are. Maybe these anthropomorphized fish aren’t explicitly facing anything that could be found in the DSM-5, but they still teach us about appreciating each other with our differences, not in spite of them. Unlike Winnie the Pooh, there is no test to see which “Nemo” character you are. There is only a heartwarming tale of complex characters that navigate the depths of the ocean and even deeper expanse of the mind. Even if we can’t find a diagnosis for ourselves, we could always use a gentle reminder to support one another on all of our own adventures.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.