Despite now being a senior, Akshara Anand has never had a female computer science professor.

“At each level, computer science weeds people out. Even in my CS201 [Data Structures and Algorithms] class, I noticed that it was very heavily male-dominated and also Asian and white male dominated,” said Anand, a co-president of the Duke Technology Scholars Program.

In the last 10 years, no students who enrolled in Duke’s computer science doctorate program indicated that they are Black. While each matriculating class has had between 53 and 67 men, there have only been 9 to 16 women in each class. Of the 744 students who have gone through the program, 513 were international students and 231 were United States or Puerto Rican citizens. While 71% identified as white, 22.1% identified as Asian and only 2.6% identified as Hispanic or Latinx.

Students in Duke’s undergraduate computer science department—the University’s most popular undergraduate program—have noticed similar problems with diversity in their experiences.

“Unfortunately, I do feel like there is not much diversity in computer science at Duke,” said senior Morgan Langenhagen, also co-president of the Duke Technology Scholars Program.

Sophomore Charlotte Hallisey shared a similar anecdote.

“Looking at the gender ratios in my computer science classes at Duke, there is a clear gender imbalance. It often feels that I am one of just a few in my classes who are female and, as I go into more advanced classes in the major, it seems as though each time, the number of females gets smaller and smaller,” Hallisey wrote in an email.

In speaking with her undergraduate student mentees, Cecilé Sadler, who graduated this year with a master of science in computer engineering, described a similar weed-out process that leaves the few remaining women and BIPOC students feeling “isolated.”

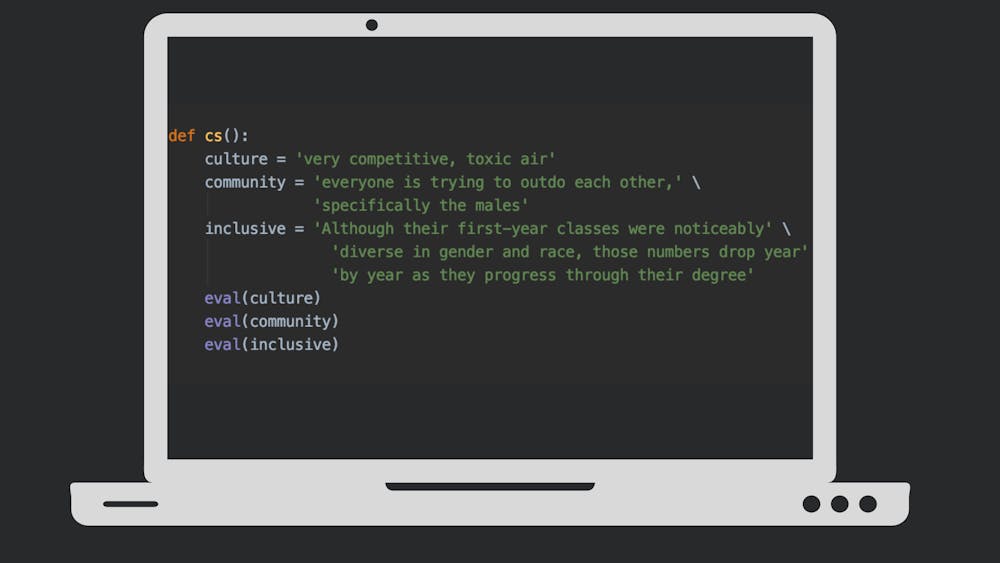

“Although their first-year classes were noticeably diverse in gender and race, those numbers drop year by year as they progress through their degree,” Sadler wrote. She feels this demonstrates a gap between the measures to encourage underrepresented groups to join computer science and the support mechanisms to keep them there.

This weed-out phenomenon, which disproportionately affects marginalized communities, is due to the “very competitive, toxic air to the computer science major where everyone is trying to outdo each other, specifically the males,” Langenhagen said.

“It is true that there are fewer women and racial minorities in computer students in CS201 versus CS101 [Introduction to Computer Science]. And I wouldn't be surprised if that's an actual trend (versus the few numbers that I have). But that is a question that can be answered by data, not just an anecdote from me,” wrote Kristin Stephens-Martinez, assistant professor of the practice of computer science, in an email to The Chronicle.

When asked about data on the demographics of students who have left the computer science department, Susan Rodger, professor of the practice and director of undergraduate studies for computer science, wrote that they “do not track that information.”

After participating in a diversity-oriented tech program at Uber her first year, Anand said her friends questioned why these programs existed.

Anand said that comments like these make him feel as though people don’t “understand the systemic differences and inequalities” underrepresented students face.

“You started programming when you were 9. I started programming senior year of high school, and there is a very large difference there,” Anand said.

Anand said that people who come from represented groups “don't really understand the struggle and imposter syndrome that people in underrepresented groups in Duke CS go through on a daily basis."

Furthermore, despite being seniors, Anand has never had a female professor in computer science and Langenhagen had her first one last semester.

They were both interested in Race, Gender, Class & Computing, a course taught by Nicki Washington, professor of the practice in computer science, but could not take it because it did not contribute to CS major requirements. Luckily, this problem will be alleviated in future semesters as the class is soon to be permanently registered as CS240.

Senior Katherine Barbano, co-president of Duke Women in Technology, said that she has been “pretty lucky to take classes with a few [female professors], but the majority of professors are definitely still male.”

As a computer science and electrical and computer engineering double major, Barbano has found a stronger presence of women in her computer science classes compared to her ECE classes. “Although I think there is a substantial amount of gender diversity, I think that there’s a lot less racial diversity in both the students and the professors,” Barbano said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

The 3C fellowship

To improve diversity and cultural understanding in the University’s computer science department, two Duke professors and a graduate student formed the Identity in Computing Group, a group of researchers dedicated to “studying the impact of identity on computing” and identifying “strategies for making computing more equitable and inclusive.”

One of the group’s primary projects include the Cultural Competence in Computing (3C) Fellows, a professional development program that aims to help faculty understand topics of identity and the historical context behind computing. 3C now has 144 fellows from 67 organizations across four countries. Other initiatives include the new Race, Gender, Class & Computing course and the Cultural Competence in Computing Assessment.

The Identity in Computing Group was founded by Washington, Sadler and Shaundra Daily, associate professor of the practice in the department of electrical and computer engineering. They are the three current researchers in the group.

Washington began developing these initiatives in summer 2020 before she started teaching at Duke. She described a conversation on a computer science education listserv following the murder of George Floyd, which she “chimed in on, highly offended as a Black woman in response to something that was said.”

This conversation started a “dialogue in the ways in which we’re failing students by not talking about certain topics like race and identity,” Washington said.

Washington hopes that the 3C fellowship will continue each year and that after completing the program, educators will “build their own course, module within a course, or activity” that incorporates the themes of identity into their respective CS curricula.

“Having a class like [her Race, Gender, Class, & Computing course] is fine, but having a class like that just at Duke doesn’t solve this bigger problem,” Washington said. “So this would be a great way to scale it.”

Daily also described the 3C program as an important tool for inclusivity at Duke.

“3C is really about educating educators. You see people going through masters, PhDs in computing and still leaving tech within five to seven years because the environments are toxic,” Daily said. “What I’m excited about is 3C’s focus on institutional transformation. It’s not about fixing the student. It’s about changing the environment that students are in.”

Stephens-Martinez also noted that both industry and academia are partly to blame for the computer science department’s lack of diversity.

“In some ways, it’s the industry’s fault, and in some ways, it’s academia’s fault because we are training the people that are going into the industry,” Stephens-Martinez said.

She couldn’t be a part of the 3C program this semester due to her hectic schedule but plans to be a part of it next fall.

“In American culture, we love to glorify the underdog that made it to the end. The problem is that the underdog had to overcome a lot of things and they made it to the end despite the system. But we don’t want the system to be that way,” Stephens-Martinez said.

Anand noted that she believes the issues with diversity in computer science are not the fault of Duke or its faculty.

"I think it's just a lot of the systemic issues with computer science as a whole, and going to a prestigious school, you're bound to have this happen," Anand said.

Anand noted that it is a "deep-rooted issue that's something that will take years to get better at" but believes Duke is moving in the right direction with the steps it's taking, which makes her feel hopeful.

She and Langenhagen agreed that the initiatives proposed by Washington and other faculty "are going to be great." Anand added that going forward, she wished there was more support from faculty in terms of advising.

She cited Stephens-Martinez as one of the incredible women professors there are in Duke's computer science department but said that she "wished there were more avenues to talk to them about their experiences and learn from them and have a little bit more faculty-to-student connection."

"I feel like every computer science class you take, it’s pretty big—there are some smaller ones, but I feel like you’re not getting those close relationships that you might get in another department," Anand added.

Rodger wrote that the department also supports Washington’s initiatives.

“We were very excited to hire Nicki Washington last spring,” Rodger wrote in an email. “The computer science department is having a lot of conversations on how we can improve the diversity in the department.”

Rodger wrote that she has been involved in the computer science department for about 27 years, and in the first 20 years, there were only three women faculty and zero secondary women faculty. Rodger wrote that there are now nine women faculty in the department and another nine women who are secondary faculty.

Sadler joined the Identity in Computing Group as an independent study after connecting with Washington last summer. She now works as a graduate research assistant “to help bring the vision for the 3C Fellows program to life,” she wrote in an email.

“As a graduate student who is a Black woman, I know firsthand the need for work the Identity in Computing Group is doing to transform computing departments,” Sadler wrote.

Where to go from here

Moving forward, faculty are “in between a rock and a hard place,” Stephens-Martinez said, because it can be difficult to try out new techniques in classes if you’re unsure of their efficacy. For example, Stephens-Martinez explained how she tried grouping students into pods, in order to foster community but ended up scrapping the pod system halfway through the semester because it wasn’t working.

“Experiments should be allowed to fail. The problem is people don’t forgive you for that,” Stephens-Martinez said.

She also worries that a failed classroom experiment will cause students to walk away from CS. “You don’t want collateral damage, but you also want things to improve.”

“One of the biggest ways to show people they are represented is to have professors who are women and racial minorities, which is something that I think Duke still needs to work to move towards,” Barbano said.

Hallisey similarly emphasized the importance of representative role models in the department.

“My academic advisor Professor Roger was my CS101 professor, which gave me a female in computer science to look up to from when I first started looking into the subject. I also feel as though the computer science culture is greatly collaborative and always encouraging and I look forward to three more years at Duke pursuing it,” Hallisey wrote.

With Washington’s initiatives, Duke’s computer science department seems to be moving in a positive direction.

“When systems that were not originally designed for people who are not cisgender, heterosexual, white or Asian men are transformed to spaces where all identities and voices are seen, heard, and most importantly valued, then the field of computing becomes that much stronger,” Sadler wrote.

“But first we must acknowledge the areas for growth, educate ourselves, and be intentional about our resolutions to address the issues that we find,” Sadler added. “That is exactly what the Identity in Computing Group is doing.”

Editor's note: This article has been updated to include more content from the interview with Anand and Langenhagen.

Madeleine Berger is a Trinity senior and an editor at large of The Chronicle's 119th volume.