At least three coronavirus variants have been identified in positive Duke-administered tests since the start of the semester. Who are Duke’s variant hunters, and how do they identify different versions of the virus?

Duke’s virus-sequencing efforts take place at the genome sequencing core facility in the Chesterfield Building in downtown Durham. University sequencing machines can identify changes on the level of a single base in the SARS-CoV-2 genome, which has nearly 30,000 bases overall.

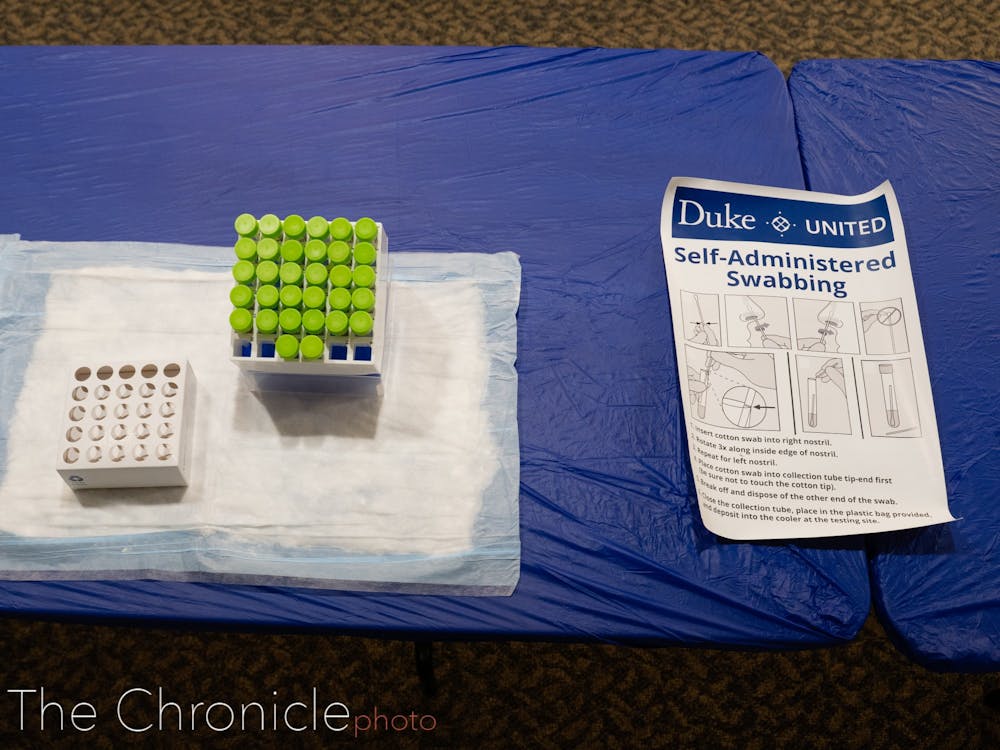

A small part of every surveillance test sample is tested for the presence of the virus. If a test is positive, the remaining sample is taken to the downtown facility for sequencing.

“When the swabs are taken, if you’re infected, there would be virus in that swab. The virus’ genome is RNA, and so we have to first take that RNA, extract it and turn it into DNA,” said Gregory Wray, director of the Center for Genomic and Computational Biology, which oversees the core facility. “And then from that DNA, we use an amplification process called [polymerase chain reaction]—it’s the same as the test uses, except instead of making one or two PCR products, we make products across the entire genome.”

This technique allows the sequencing team to construct a map of the entire virus that has infected a person. Samples can be obtained, sequenced and processed in less than 48 hours, and every positive sample is sequenced.

The core team consists of Wray, an operations manager and six technicians, two of whom are fully dedicated to sequencing. Wray explained that sequencing allows researchers to develop an understanding of transmission patterns. He added that sequencing data likely played a role in administrators’ decision to instate the undergraduate stay-in-place order in mid-March.

The sequencing team does not have any information about infected individuals beyond de-identified case numbers, said Wray. Once a positive test has been analyzed, the sequencing group hands the information over to an epidemiology team, which is responsible for examining case-specific variables such as which residence hall an individual lives in.

According to Wray, Duke’s sequencing core facility has existed for more than 20 years. The first coronavirus case sequences were completed at Duke in April 2020. Since then, the sequencing core has been working with the campus surveillance team and coronavirus researchers alike.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.