Before the famed "First Five" Black undergraduate students enrolled at Duke University in the fall of 1963, the Board of Trustees took the first step toward desegregation with a decision years in the making.

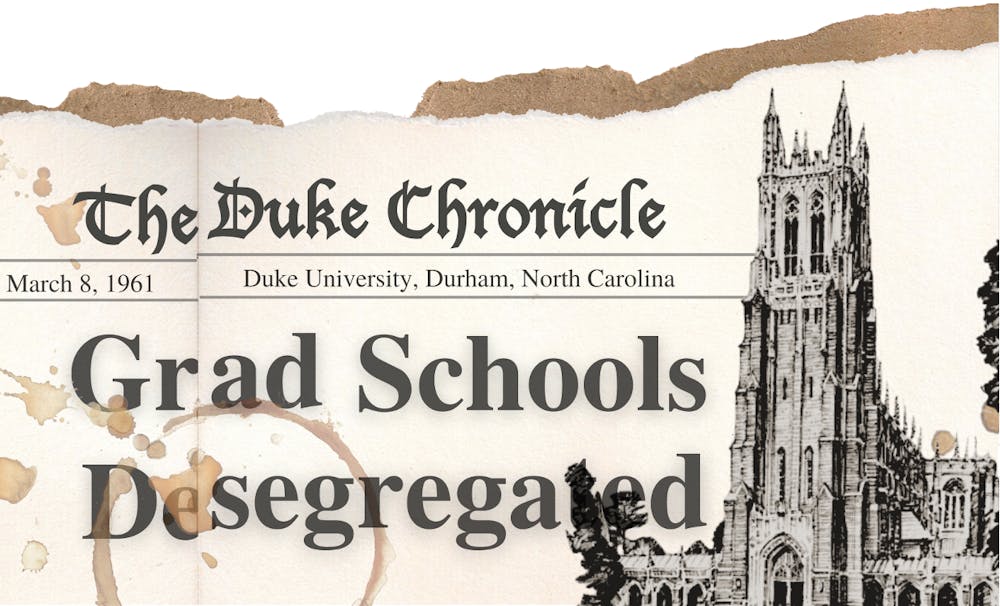

On March 8, 1961, the board announced Duke’s graduate and professional schools would accept applicants without regard to race, creed or national origin, effective the following fall. “Grad Schools Desegregated,” The Chronicle’s front-page headline read that day.

“In a move actualizing the University's leadership potential, the Trustees set a commendable example for other Southern institutions and increased the University's prestige from a national standpoint,” a Chronicle editorial two days later said of the board’s decision.

Duke changed its admissions policy for financial and reputational gain, rather than for moral or ethical reasons, records and archival documents show.

“Look at the world we're living in today and look how decisions are made in this country,” Jacqueline Looney, senior associate dean for graduate programs and associate vice provost for academic diversity, said in an interview with The Chronicle. Duke Graduate School hired Looney as the university’s first minority student recruiter in 1987.

“Moral suasion—I don’t know. It just has not worked,” she said.

Administrators and trustees wanted Duke to become a leading university in the country. A segregated admissions policy threatened the sources of money that would bolster Duke’s acclaim.

The process of desegregating the university—first its graduate and professional schools, and then its undergraduate student body—reflected Duke’s incrementalist approach to reform.

“I am a ‘gradualist,’” Arthur Hollins Edens, Duke president from 1949 to 1960, wrote in a 1953 letter. “It is my firm conviction that Duke University can and should admit negroes only when the community and constituency are prepared for it.”

Push for desegregation

Students in the Duke Divinity School first raised the issue of desegregation to the Board of Trustees in 1948, through a petition. Over the next decade, various student and faculty groups and individuals urged Duke leaders to amend its admissions policy barring Black students.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled the racial segregation of public schools unconstitutional in its decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The first Black undergraduate students enrolled at the nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1955.

The Chronicle called segregation a “barbaric tradition” in a Dec. 13, 1955 editorial.

“We charge that segregation is anti-democratic, anti-Christian, harmful propaganda to the rest of the world and incompatible with the idea of a university. Anyone who refuses to believe that segregation implies inferiority is blind,” the editorial read.

Historian Melissa Kean called the editorial the “boldest condemnation of segregation published at Duke in the 1950s” in her book “Desegregating Private Universities in the South.”

In 1957, Divinity School students again circulated a petition urging the Board to eliminate the school’s admissions policy barring Black students from consideration. The board voted on the issue for the first time. They chose to uphold the policy.

“Our own school is missing financial and academic aid imperative to the growth of an educational institution,” The Chronicle editorialized in response to the vote.

However, the paper’s editorials and student groups’ advocacy did not necessarily reflect an activist culture among the greater student body.

At the time, Duke was a “finishing school for white privilege,” said Theodore Segal, Trinity ‘77, author of “Point of Reckoning: The Fight for Racial Justice at Duke University.”

Maids made the beds and cleaned the rooms of male undergraduate students until 1968, Segal found in his research.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“White young men and women went there because their white parents went there, and they were trained in the academics and habits of how a white person comports themself in the world,” Segal said in an interview.

Duke operated within the racially segregated rules of the Jim Crow era, and its students were not immune to its ideology. Students wrote letters to the editors in The Chronicle espousing segregationist beliefs, such as a 1958 letter to the editor fearing the possibility of interracial marriage.

“The half-cracked ‘moralists’ of the North have taken the issue of ‘equal conditions for all races’ and decided that the South must kneel down and obey their commands to surrender to integration,” student James Kennedy wrote.

But more often, archival records suggest a prevailing sense of apathy among the student body regarding issues of racial justice.

“Many of us are beginning to wonder what the reason is for so few students asserting opinions and taking action on the matter of the pickets in Durham: is it because they are trying to remain calm and stable during an emotional period—or is it that they have no opinion at all to assert?” columnist Barbara Underwood wrote in the same issue of The Chronicle announcing the board’s ultimate decision to desegregate.

Regardless, the sentiments of students seemed to have little effect on the Board of Trustees’ decision-making, according to Segal’s research.

“I don't think what the Chronicle wrote or what students thought was a particularly significant factor in the decision to desegregate,” Segal said. “The reason was money and they delayed as long as they could.”

Money and reputation threatened

By the early 1960s, the federal government and national philanthropic organizations signaled they would only give money for research and educational purposes to institutions with nondiscriminatory admissions policies.

With millions of dollars in grants and contracts on the line, Duke set out to make the case for desegregation to the Board of Trustees.

“We initially proposed integration in the graduate school and professional schools only, as a starting point,” R. Taylor Cole, Duke’s provost at the time, recounted in a 1980 interview.“...We concluded that we would present the proposal to the board in terms that we thought would be fully understandable to the board … legal, economic, and educational reasons, all of which pointed toward the absolute necessity for integration.”.

Three administrators, including Cole, wrote a memo for the trustees outlining reasons for changing Duke’s admissions policy that did not stress the “moral aspects of segregation,” Cole recalled.

The memo also said that desegregating the graduate and professional schools “should not be considered an argument” for admitting Black students to the undergraduate school, Segal wrote in his book.

The Board adopted the resolution to open graduate and professional school admissions to applicants of all races on March 8, 1961.

“A possible diminution of revenues may have led to the action by the Trustees,” The Chronicle reported at the time.

Following the Board’s decision, the Duke Endowment chair wrote letters to leaders of the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation announcing the board’s move. The philanthropic giants responded affirmatively, archival documents show.

On June 2, 1962, the Board of Trustees announced that Duke would amend its undergraduate admissions to include Black students.

The first Black graduate and professional students

A handful of Indigenous, Asian, Latinx and Asian American students had enrolled at Duke as early as 1880, records show. But Black students did not attend the university until the fall of 1961, after Duke changed its graduate and professional schools’ admissions policy.

Walter Thaniel Johnson Jr. and David Robinson were the first Black students to attend Duke Law School. Ruben Lee Speaks was the first Black student to enroll in Duke Divinity School, though he enrolled with special status, as he had already received a divinity degree.

In the fall of 1962, James Eaton, Ida Stephens Owens and Odell Richardson Reuben were the first Black students to attend the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Matthew A. Zimmerman and Donald Ballard were the first Black students to enroll in the Divinity School as official degree-seeking students.

Key administrators at the graduate and professional schools directly recruited these first students.

Johnson and Robinson recalled Dean Elvin “Jack” Latty’s recruitment efforts in a 2012 interview with Duke Law School.

“Was I seeking integration? No,” Robinson said. “In fact, my entire family was opposed to it. They were concerned for my safety.” After meeting Latty during one of the dean’s recruiting trips to Howard University, Robinson found Latty to be “a most persuasive, fatherly figure. He said, ‘We’re gonna do this.’”

Owens, the first Black woman to receive a doctorate from Duke, enrolled because of the recruiting efforts of Daniel C. Tosteson, then chair of the Department of Physiology. She met him when he came to Durham’s North Carolina College, now North Carolina Central University, to scout potential graduate students.

“I am eternally grateful to Duke, eternally grateful for the fact that they allowed me to enter that school. But I’d never for one moment say if I hadn’t gone to Duke then I wouldn’t be where I am today,” Owens said in a 2014 documentary produced by Duke Graduate School. “I don’t think of it that way.”

Owens recalled her siloed studies in the laboratory, saying she didn’t know there were other Black graduate students and later Black undergraduate students at Duke until her graduation in 1967.

Looney noted the distinction between desegregation and integration.

“The bars were lifted, but [Owens] was never integrated in the community at Duke,” Looney said. “It's like when we think about diversity and inclusion … diversity is being invited to the party … inclusion is being asked to dance.”

Asked whether she thinks Duke has become fully integrated since she began recruiting minority students more than three decades ago, Looney said, “We're still dealing with some of the same issues that we dealt with in 1987. We also have made tremendous progress.”

“There is still a lot of work to do,” she said.