Between listening and glancing at subtitles to check my comprehension, calling my mom right after to discuss one of her childhood favorites and saving my thoughts somewhere to discuss with my cousin Michel — watching Brazilian films is unlike any other viewing experience I have. I learned to speak Portuguese right along with English growing up, but after years of neglect and fewer and fewer visits to see my mom’s family, my vocabulary and conversational skills are limited, and my cultural ties grow weaker by the day.

To try to counteract this, I took a Brazilian film class freshman year. The films in the class were hit or miss, but most of them were fairly modest knockoffs of Hollywood genre flicks. Then, we watched “Cidade de Deus (City of God),” one of the most recognizable pieces of Brazilian culture in Brazil, and one of the best movies I have ever seen. For the first time, I felt this incredible sense of pride watching a Brazilian movie, awestruck by the potential and talent nestled within Brazilian cinema. This motivated me to seek out others including “Central do Brasil (Central Station)” and “Hoje Eu Quero Voltar Sozinho (The Way He Looks),” which gave me the same beaming pride and cultural connection.

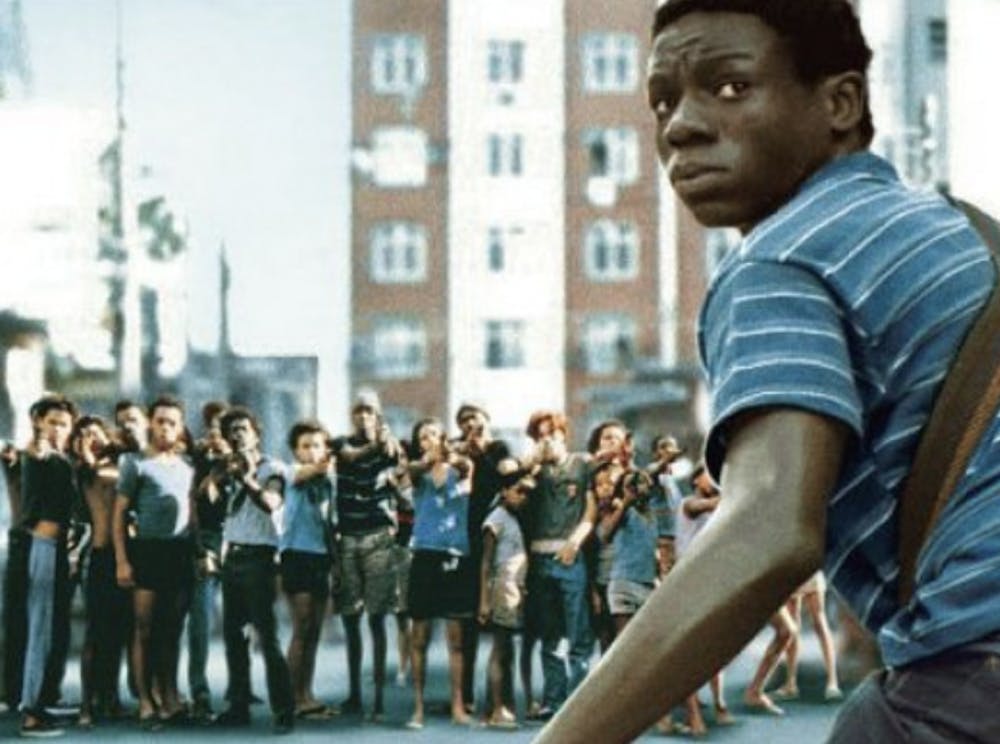

“Cidade de Deus” is a sprawling crime epic, but not a cheap Hollywood knockoff. Loosely structured and connected by the narration of aspiring teenage photographer Buscapé (Rocket) looking for a way out, “Cidade de Deus” is based on the true story of the titular favela and the rise in organized crime in the neighborhood between the 1960s and 1980s.

It explores gang violence, cycles of crime, corruption, social mobility and a whole lot more, but at its heart, “Cidade de Deus” is a story about its characters. Bené (Benny), Mané Galinha (Knockout Ned) and many others get their stories told by Buscapé throughout the runtime, and almost every character with significant screen time feels well-realized and realistic. This may be due to the fact that most of the performances are authentic, as directors Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund filled most of the cast with non-actor residents from Cidade de Deus and neighboring favelas.

Every crime saga needs a good villain, and Cidade de Deus has one of the best ever put to screen. Fit with sociopathic tendencies, a maniacal laugh when he kills and a thirst for power, Zé Pequeno (Lil Zé), played by Leandro Firmino, is an incredible embodiment of pure evil, with just enough of a shred of humanity to avoid becoming a caricature. He steals every scene, producing some of the most bone-chilling moments in cinematic history, specifically his actions at a motel in the first act and the infamous choice he forces one of his young drug distributors to make when he finds a group of young kids stealing from a bakery.

When it came time to write about “Cidade de Deus” for class, I wanted to focus on these powerful performances, the unique editing, the perfect score or the exciting camera work, but I couldn’t help but think about the film’s production, response and aftermath, all of which have complicated its legacy.

While casting actual members of the favelas helped improve the authenticity of the film, these actors were not paid their fair share. Actors, even those playing main characters, received anywhere from five thousand to ten thousand reais for a film that made roughly 100 million reais. The treatment of the actors outside of just pay is not much better. While many wanted to continue as actors, not everyone found their footing, as the filmmakers provided little support in terms of career advice or development. As exposed in a follow-up documentary, “City of God - 10 Years Later,” this was the film to put some actors, like Alice Braga, on the map, launching a lucrative film career, but for others, like Leandro Firmino, roles were hard to come by. Many of the actors who helped this film become such a box office smash remain poor, living in the same favelas that they did before the film’s release.

Some critics have argued that the film itself glorifies poverty and violence in the favelas, reinforcing stereotypes about these communities while not adequately portraying the rich culture of favelas like Cidade de Deus. While I do not think this is completely accurate, as the food, music and other elements of daily life do play a role in the film and depictions are largely based on the real life drug wars during this time, it is certainly a key part of the conversation for the film as it ages. One related concern, though, is that the film, which was a cultural phenomenon in Brazil and worldwide, has sparked a wave of morally dubious “favela tourism,” with tours now the fourth largest tourism attraction in Brazil. It is the responsibility of filmmakers to respect and uplift the communities that they interact with, but this clearly was not the case with “Cidade de Deus.”

The soaring heights that the film achieves during its 130 minutes cannot excuse any of these surrounding issues. I do not feel the same sense of beaming pride as I once did for “Cidade de Deus.” Here is to hoping Brazilian cinema reaches these heights once again — without needing a follow-up documentary a decade later.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.