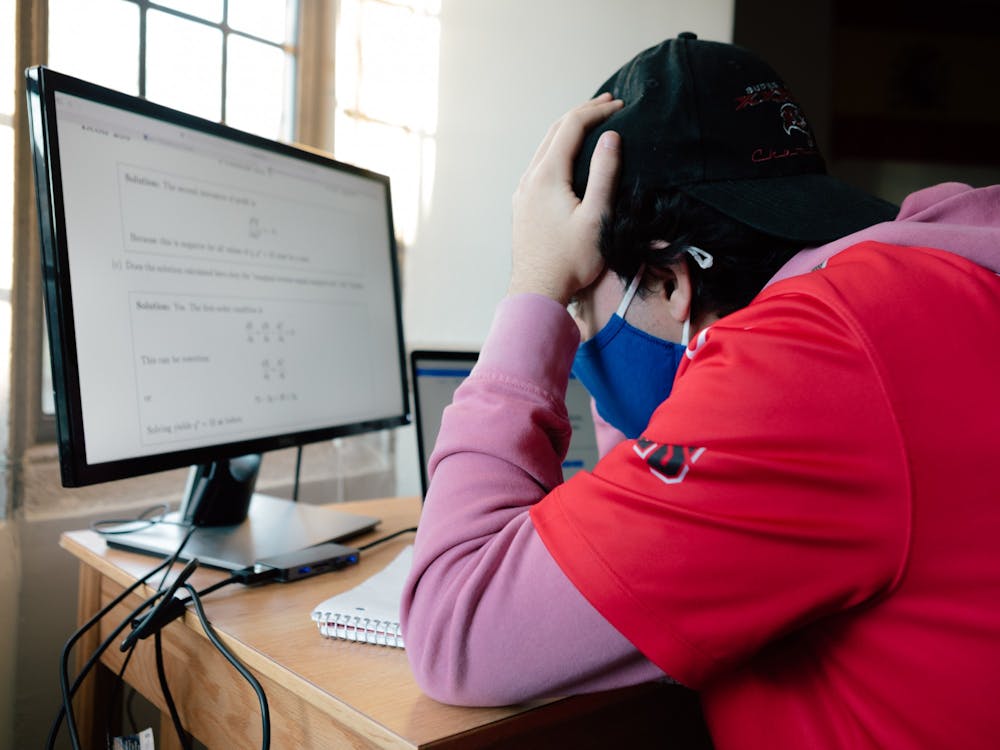

Students felt high levels of loneliness, social isolation and concern about their mental health during the fall semester due to COVID-19, with students of marginalized identities and historically underrepresented backgrounds reporting greater stress levels, according to a Duke survey.

The Office of Undergraduate Education Research Group conducted an online survey of Duke undergraduates between Nov. 1 and Nov. 16 to assess student stress, mental health and well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. The Duke Student Government’s Mental Health Caucus helped revise and distribute the survey.

“Our goal with the project was to collect empirical evidence to learn what aspects of the previous semester were especially challenging and stressful for students, and what aspects may have been less challenging than we might have thought,” wrote Molly Weeks, director of research for the OUE, in an email.

1,015 Duke undergrads—about 15.4% of those invited to participate—completed the survey. Weeks wrote that the sample was generally representative of the target population in terms of race and ethnicity as well as students who self-identified as first-generation and/or low-income. There was a slight overrepresentation of first and second-year students and students who identified as women, Weeks wrote.

The survey results were compared with those from the Student Resilience and Well-Being Project (SRWBP) study from previous years, where possible.

Part of the survey involved participants rating sources of stress from the semester. Students—77.8% of respondents—were most likely to attribute the lack of breaks during the fall semester as being “very stressful” or “extremely stressful.” More than 67% of students said that the compressed timeline for the fall was “very” or “extremely” stressful.

Duke has revised the spring semester calendar to include a two-day break, as well as a wellness day where classes are not officially canceled but faculty are encouraged to have students participate in wellness activities instead of coursework.

Other top student stressors included global and national responses to COVID-19; the 2020 U.S. election; concerns about missing out on curricular or co-curricular opportunities; managing academic workload; constraints on hobbies, activities or leisure time; concern for mental health; Zoom fatigue and U.S. and international politics.

Another takeaway from the study was that “loneliness and social isolation were a significant problem for students last semester,” Weeks wrote.

Almost half of students rated social isolation as “very” or “extremely” stressful. Just under 10% of respondents said they were lonely “most of the time” or “always” in a variety of environments, compared to 1% in the SRWBP results from previous years.

The highest percentage of respondents—33%—reported loneliness during class, followed by in the evening, while studying, during free time and at bed time. These percentages were all higher than those reported in the SRWBP.

Weeks wrote that the results provide concrete evidence supporting a need for “opportunities for meaningful social connection with friends, peers, and others at Duke...within the significant constraints of pandemic public health measures.”

The survey also found that mental health was a large concern for students. According to the survey results, many participants reported experiencing “moderate (23.5%) or severe (20.5%) symptoms of depression and anxiety over the past two weeks.” Nearly a fifth of respondents reported feeling “overwhelmed and unable to handle the demands of life fairly often or very often over the past month,” compared to just under 4% in the previous SRWBP results.

Academic engagement levels and feelings of belonging at Duke, however, did not decline as a result of the pandemic, “suggesting that students are still connecting with their academic work and the institution as a whole,” Weeks wrote.

Approximately 61% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they felt like they belonged at Duke, and just under 77% of respondents reported high levels of academic enthusiasm and engagement. These percentages did not differ significantly from those in the SRWBP study.

The study also looked at contextual and demographic effects, including living arrangements (students living on campus versus students living in off-campus in Durham and students living outside of Durham), race and ethnicity, identification as first-generation or low-income, identification as LGBTQ+, gender identity, and being a student-athlete.

Weeks wrote that since most on-campus students were first-years and sophomores, attributing differences between the groups to class year or location is difficult. Nevertheless, “being away from Durham has made it more difficult for students to develop or sustain a strong sense of belonging to Duke, and made it more difficult to develop or sustain friendships with other Duke students,” Weeks wrote.

First-generation or low-income students, underrepresented minority students, and LGBTQ+ students generally had higher levels of stress and mental health concerns than other students. According to the survey results, however, these findings are “consistent with the literature generally and are not necessarily specific to the pandemic.”

Weeks noted that stressors strongly rooted in the pandemic, including worries about health and safety and government responses to cases, may begin to diminish quickly. Others, such as stress related to the toll that the pandemic has taken on the economy, may persist.

“A key question is what the trajectory of recovery will look like for issues related to social connection and isolation,” Weeks wrote. “In some ways [it] could go back to “normal” fairly quickly, but in other ways could potentially show lingering effects.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

DSG is using the findings from the survey to “assess how we can best support Duke students’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic and moving forward,” wrote first-year Nicole Rosenzweig, co-chair of the DSG mental health caucus, in an email.

One significant change that came from DSG’s efforts was the addition of the two-day break and wellness day to the spring semester, she wrote.

“The process began with advocacy surrounding the need to have Election Day off in 2020, which eventually transitioned to a larger discussion about mental health and break days for the spring semester,” Rosenzweig wrote.

She wrote that DSG’s Executive Board sent an email to Provost Sally Kornbluth and other stakeholders outlining the degradation of student well-being and consequent need for scheduled break days. The change came “after various email exchanges, presentations, meetings, and the recommendation of specific dates,” Rosenzweig wrote.

If you are looking for remote or in-person mental health resources, you can find them in guides created by The Chronicle and Duke Student Government.