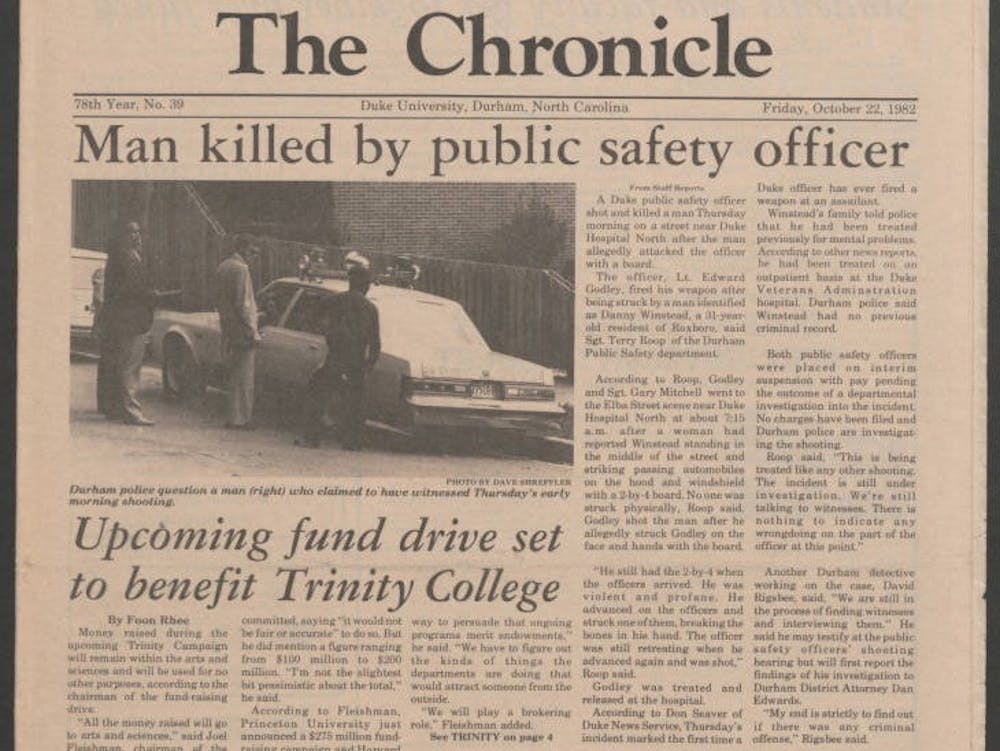

First in a series about use of force by Duke law enforcement officers. Read the second part, about the other time an officer used deadly force, and the third, a review of how DUPD officers have used force in recent years.

Thirty-eight years ago, Duke public safety officers shot and killed a man in what was, according to Duke, the first death involving University officers.

Public safety officers Lt. Edward Godley and Sgt. Gary Mitchell shot and killed Danny Lee Winstead near Duke Hospital North on the morning of Oct. 21, 1982. University spokesperson Don Seaver told The Chronicle at the time this was the first time a Duke officer “fired a weapon at an assailant.”

Winstead’s story resurfaced ten years ago in relation to Aaron Lorenzo Dorsey’s death, and Dorsey’s death was in turn highlighted more recently in the demands from the student-led Black Coalition Against Policing. The Chronicle covered Winstead’s death when it occurred, mostly relying on reports from the Durham Morning Herald, but some details and witness accounts were absent. This article pieces together family interviews, news reports, editorials and medical documents to create a narrative of what happened on the day of Winstead’s death and in the aftermath.

To aid in reporting, The Chronicle requested the autopsy and investigation reports for Winstead from the N.C. Office of the Chief Medical Examiner on July 16, 2020. The Chronicle received a toxicology report Jul. 27 and the investigation report Dec. 16. The office informed The Chronicle Aug. 11 that it was “unclear” whether an autopsy existed for Winstead, but the investigation report states that “a more complete description” of the incident was included in the autopsy.

Godley and Mitchell could not be reached for this article.

Gladys Love and Danny Lee Winstead with their daughters, Sherri and Dawn.

Who was Danny Lee Winstead?

Winstead grew up in Roxboro, N.C. He was co-captain of the football team at Person High School, and he married his childhood sweetheart, Gladys Love, shortly after graduating in 1970. They were young, Love said, but she was pregnant and wanted her children to have a father. They had two daughters, Sherri and Dawn.

Not long after graduating, Winstead enlisted as a U.S. Army private and served in Vietnam. When he returned from the military, the effects were evident.

“He was having mental problems before he went to the military,” Love said. “But once he got out of the military, it became more severe.”

Winstead seemed paranoid, according to Love. His mental health eventually deteriorated to the point where it hindered his ability to keep a job, and it was then that he began to seek help so he could continue to support his family.

He tried “many, many, many times” to seek treatment at the Duke Veterans Affairs Hospital to no avail, Love said. She and Danny Winstead eventually separated when their daughters were young, according to Sherri Winstead.

Danny Lee Winstead.

Sherri Winstead said that she had a good relationship with her father, although she was not as close to him as her sister had been. She was 11 when Danny Winstead was killed.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“I remember when they came and got us from school after it had happened,” Sherri Winstead said. “The family being around, the sadness surrounding all of this, and the services.”

Although Sherri Winstead knew her father had been shot, she didn’t learn the details of the incident until she was older. Despite not having a close relationship, she said she now understands what her father was going through at that time, and she feels his life was disregarded.

“There’s so much that he would have missed out on, not being in our lives,” she said. “It’s definitely a loss.”

At the same time, she doesn’t hold any anger toward Duke officers and believes they were genuinely acting in fear of their lives.

“Of course I wish the situation was handled differently but I do recognize my dad was not in the right state of mind and was doing wrong to even have this situation occur in the first place,” Sherri Winstead wrote in a message. “I have always had sympathy for the officers as they have had to live with that event and the fact that they took a life.”

According to the Morning Herald, Danny Winstead was a frequent visitor of the neighborhood where he eventually died. Several people who knew him wondered what happened and relayed positive statements about him to the Herald. One person remarked that “something or someone must have set [Winstead] off” the day of the incident.

Gilbert Ragland told the Herald that he and Winstead had grown up together, and that they saw each other nearly every night.

“When I went down there [that morning], he was lying in the parking lot,” Ragland said.

Love said that it may have been hard for Winstead to receive help as a Black man, because they are often assumed to be lazy.

“I don’t think he had a chance,” she said.

The Duke department of public safety

The department of public safety was the direct predecessor to the Duke University Police Department, adopting the latter name in June 1996. Public safety, previously known as the traffic and safety department, underwent its greatest expansion under Chief of Public Safety Paul Dumas, who arrived at Duke in late 1971.

“[Public safety] was a good department when I came, but I made changes that fit my own style of administration,” Dumas told The Chronicle in 1984.

Under Dumas, the department “more than doubled” in personnel and rearranged its priorities to focus on fire protection, rape prevention and “crime against property.” The traffic and policing functions were separated and a detective unit was formed. The department also expanded to include a division dedicated to protecting Duke Hospital North.

At the time of Dumas’ 1984 interview with The Chronicle, the department had a $2 million budget, which he managed. The aforementioned report revealed that Duke budgeted just over $1 billion for traffic and security in the 1978-79 fiscal year, with 47% of the budget going toward Duke hospitals. Budget cuts were proposed in 1980 for public safety but deemed “undesirable”, according to the same report.

Apart from budgeting and hiring, Dumas was also responsible for investigating internal cases, including complaints.

Dumas died in 2001 at the age of 67, according to a Duke obituary from the time.

Winstead encounters Duke public safety

On the morning of Oct. 21, 1982, Winstead was observed striking vehicles with a two-by-four wooden board. Henry Bryant, manager of the Dutch Village Motel restaurant, told the Carolina Times that someone entered the restaurant and asked him to call the police because “someone was smashing car windows in the parking lot.”

Public safety arrived at the area between Elba and Elf Road near a Duke parking deck at 7:15 a.m. after receiving reports of an assault, according to the Herald. The investigation report says that Winstead struck a woman, but the Herald reported that officers learned upon arrival that Winstead had not struck anyone.

Godley and Mitchell were among those that arrived at the scene, but the exact number of officers present was disputed. Bryant told the Carolina Times that five officers drove up to the scene, while Durham resident Joyce Roberts told the Herald that she only saw three officers. Durham Public Safety Officer J.W. Platt told the Herald that six officers were at the scene, including Godley and Mitchell.

The investigation report, completed by Durham Public Safety detective David Rigsbee, says that Godley tried to “physically stop” Winstead from harming someone before being “pushed backwards and threatened” with the board. Public Safety Officer P.M. DeTomo told Winstead to drop the board, according to the Herald, but Winstead continued to advance toward the officers.

Winstead then struck Godley.

“He swung at one of the officers, and the officer threw up his arm to block the blow,” Bryant told the Carolina Times. “And then the cop shot the man who was holding the piece of wood.”

Witnesses told the Carolina Times that they heard four or five shots. The Herald reported that Godley fired his revolver three times and Mitchell fired his gun once. At least one witness said that some of the shots fired were warning shots.

“I still say the public safety officer done right because they did try to talk to him, and they did fire three warning shots,” Roberts told the Herald. “They told him to drop the club, and he kept swinging.”

Durham Public Safety Sgt. Terry Roop told The Chronicle that Winstead was “violent and profane,” and that he had broken the bones in Godley’s hand. The Herald reported that Godley was treated for “cuts and bruises on his wrist and hand.”

“The officer was still retreating when [Winstead] advanced again and was shot,” Roop told The Chronicle.

The Herald also reported that Winstead continued to advance toward Godley after the warning shots. However, some witnesses told the Carolina Times that Winstead had been fleeing.

“I’m pretty sure one of the shots hit the man in the back,” Bryant said.

Bryant’s statement was corroborated by Lilly Poole, who lived nearby. She exited her home after hearing the first shot and said she saw Winstead trying to run behind a car.

“I heard three more shots,” Poole told the Carolina Times. “The second and third ones must have caught him while he was turning away from them, but that last shot must have hit him in the back.”

When asked if she had heard officers fire any warning shots, she insisted “all the shots they fired were into that boy.”

The investigation report stated that Godley fired two rounds at Winstead, both of which hit him. Winstead then approached Mitchell, according to the report, and Godley fired a third time while Mitchell shot at Winstead.

Winstead collapsed in a parking lot at Campus Apartments on Elf Street, where a physician began CPR. He was transported to Duke Hospital North where he was declared dead.

The aftermath

After the shooting, Godley and Mitchell were placed on interim suspension with pay pending a departmental investigation. However, Dumas told The Chronicle Oct. 25, 1982 that he was “relying heavily” on the investigation by Durham Public Safety because Duke’s public safety department did not have an internal affairs department to handle the case by itself.

When Chronicle reporters questioned Dumas about the shooting, he refused to say how many shots were fired.

“I don’t want to discuss the details of the shooting until I get the autopsy report,” Dumas said. “I’ll just let the scientists tell me how many shots were fired and where the deceased was hit.”

Dumas also told the Carolina Times that it wasn’t departmental policy to fire warning shots, but declined to address reports about whether they occurred.

The day after the shooting, the Herald reported that Winstead had been shot in the chest, abdomen and hand. In response, Dumas said that he “did not know where the Herald had gotten its information” and that it was “unlikely” Durham Public Safety had already received Winstead’s autopsy.

The Carolina Times later reported Oct. 30 that Winstead had been shot twice in the abdomen and once in the chest. This reporter was unable to clarify the discrepancies, as the location of Winstead’s wounds would have been included in the autopsy report which was never received. The investigation report declared the cause of death to be a gunshot wound to the chest.

In late October 1982, the case went before a grand jury to determine whether Godley and Mitchell would be indicted, particularly for voluntary manslaughter. Five public safety officers and five civilians testified during the trial, as well as Rigsbee.

The jury eventually decided not to indict the officers on any charges Nov. 2, deeming the shooting justified. A University spokesperson told the Herald that Godley and Mitchell had been reinstated, although Dumas told The Chronicle that Godley was still unable to work due to his injuries.

“I’m obviously glad with what the grand jury decided,” Dumas said.

Dumas also told The Chronicle that the departmental inquiry was closed and the matter would not be investigated any further. The internal investigation lasted 13 days, in comparison to two months for Dorsey’s death in 2010.

Upon reinstatement, Godley and Mitchell had to re-complete firearms training, The Chronicle reported Nov. 11, 1982. Officers had to complete training with 80 percent accuracy in three tests during the day and one at night in order to receive firearms.

When asked about the shooting, John Goodfellow, weapons training officer and chief of Medical Center public safety, said that Duke was “the type of place where they’re not just going to sit back and think it’s going to go away.”

“Certainly we’re going to do anything we can to prevent another shooting,” Goodfellow said.

Dumas told The Chronicle in 1978 that firearms were only meant to be used when the officer or another person was “about to be killed or permanently injured, and after all other means have failed.” In the same article, it was mentioned that officers carried mace for “rough situations” short of lethal force and that an officer who pulled a gun on a dog in years prior was fired.

An anonymous Duke officer told the Carolina Times that officers were trained to “fire at the largest part of the suspect’s body, which is generally intended to kill.”

Community response

Some members of the Duke community questioned whether officers had truly exhausted all means to deescalate the situation. In an Oct. 26 column titled “Crucial questions,” The Chronicle’s editorial board called for an “exhaustive investigation,” asking how many shots were fired and under what conditions.

“Certainly a two-by-four can be a deadly weapon, but according to some news accounts as many as six officers were at the scene when the shooting started,” the board wrote. “If that is correct, it seems odd that they had to shoot Winstead to stop him.”

A Carolina Times editorial argued that while officers could not have been expected to know that Winstead had a history of mental illness, his death still could not be justified, given no indication that he “would have been of any danger to society.”

“Any of us, sane today, could be in a Durham parking lot swinging a two by four at cars tomorrow,” the editorial reads. “As farfetched as that may sound today, ask yourself nevertheless, if it should happen would you want to face an officer who goes from warning shots to killing shots?”

Nadia Bey, Trinity '23, was managing editor for The Chronicle's 117th volume and digital strategy director for Volume 118.