Over the course of a five-year span beginning in 2014, the current state of the Duke men’s basketball program was firmly established.

Amidst a flurry of five-star talent arriving (and departing) in Durham, four Black high school prospects, all ranked as the top player in their class, chose to experience college basketball in a Blue Devil uniform.

For Jahlil Okafor, Harry Giles, Marvin Bagley III and R.J. Barrett, the road to Cameron Indoor Stadium wasn’t a shocking one, though that path had been paved almost 40 years prior by a Black No. 1 overall recruit from West Philadelphia who also chose the Blue Devils.

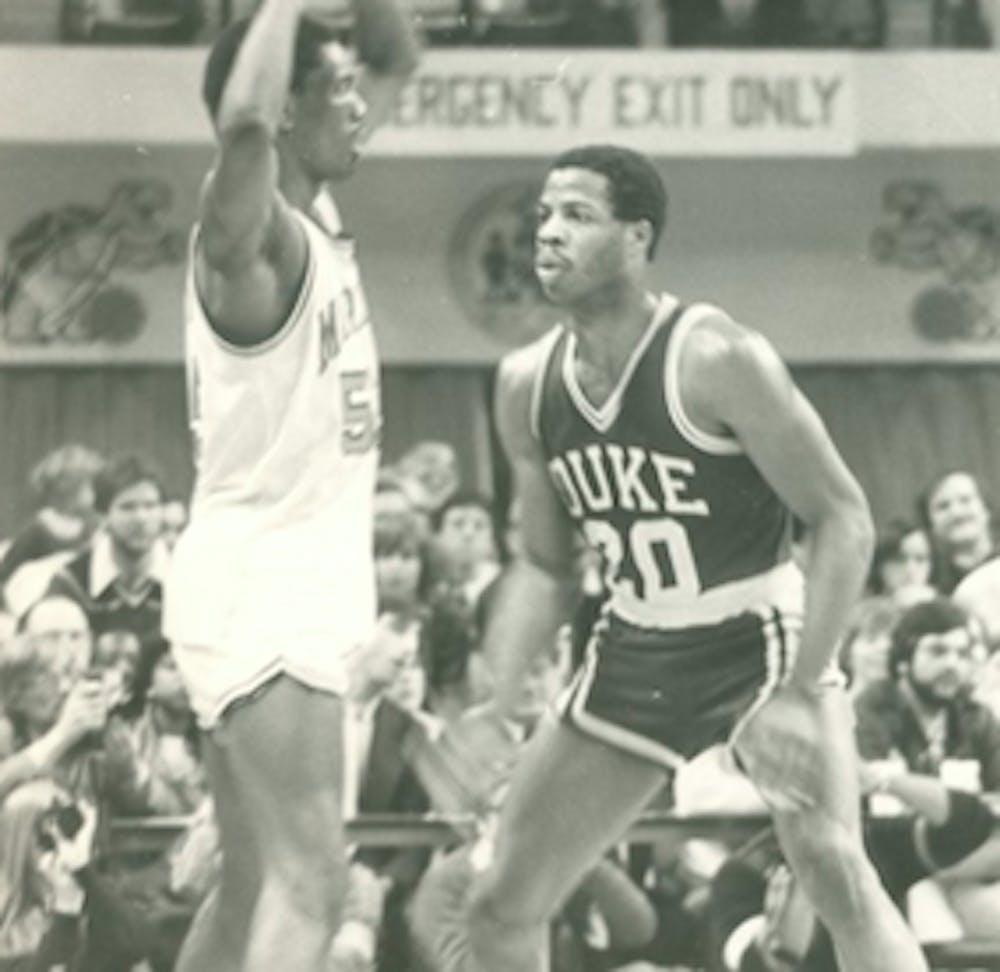

Gene Banks doesn’t have his jersey retired in Cameron and played only his senior campaign under legendary head coach Mike Krzyzewski, however, his underrated Duke career ranks as one of the more significant in program history.

‘Divine intervention’

Kenny Dennard, his close friend and teammate in college, describes Banks as, “like Muhammad Ali to me,” an apt description for the bright and flashy persona of the high school basketball phenom.

Blossoming at West Philadelphia High School, Banks rose to the top of a class that included future Hall of Famer Magic Johnson. The man nicknamed “Tinkerbell” was also selected to the first ever McDonald’s All-American team and took home MVP honors in the ensuing exhibition game.

Banks could have played for any program in the country and had already taken visits to Notre Dame, Michigan, UCLA, N.C. State and North Carolina. But from what Banks describes as “divine intervention,” his English teacher urged him to travel to Duke for his final official visit. To get his teacher off his back, Banks obliged and agreed to take a trip to Durham.

The Blue Devils were led by a young, easygoing coach named Bill Foster, who took over the program in 1974 to bring it back to national prominence. When Foster first dropped off a recruiting brochure for Banks, the information inside detailed the positives of the school, rather than the basketball program.

“His quirks and the things that [Foster] did really caught my attention because of the way he was,” Banks remembers. “Very caring, sarcastic, funny, whimsical. It got my attention because I met a lot of coaches who were pretty serious.”

While Duke was a struggling program and didn’t have a strong history of recruiting Black players, it was something about the landscape, the size and the people that led to Banks shocking the college basketball world and committing to the Blue Devils.

“There was a small contingent of Blacks there that were very connected with each other,” Banks said. “I liked the diversity of the school. Students come from different ethnicities and different cultures. It was really a school where I felt more comfortable.”

Despite winning just two conference games the year prior, Duke was suddenly armed with a new superstar to complement its returning talent, and Banks’ commitment would set the tone for the 40-plus years of recruiting success that followed.

“I thought that was a great thing for Duke and for Bill Foster,” Krzyzewski said this preseason. “That was a big commitment in the late 70s, along with [Jim] Spanarkel, Kenny Dennard, Mike Gminski. For a couple years there, they were one of the top teams.”

Claudius “C.B.” Claiborne integrated the Duke program as its first African-American basketball player in 1966, recruited to Durham by legendary coach and former Blue Devil assistant Chuck Daly. However, Banks was the first high-profile Black athlete to don a Duke uniform, attracting national attention the moment he arrived on campus.

“It all went smoothly. I never felt there was pressure,” Banks said on having that role. “I never thought of it as a responsibility. And Bill Foster was great with that. He allowed me to spread my wings. He allowed me to be articulate. He allowed me to have the stage, and I loved it.”

‘We complemented each other’

Banks arrived in Durham hungry to prove himself as a freshman, and even in pickup games in the I.M. Building, he sought to dazzle. It was a pickup session there when Banks drove the lane for a big dunk attempt, but was surprisingly met at the rim by Dennard. The two freshman classmates crashed to the ground and looked at each other before Banks exclaimed, “Yeah! That’s how you play the game!”

It was all smiles as a lifelong friendship blossomed from that competitive spirit on the court.

Dennard committed to the Blue Devils the previous November with much less fanfare than Banks, though he was a major contributor immediately as a freshman. The 6-foot-8 forward hailed from nearby rural King, N.C., a completely different environment than what his star classmate had experienced growing up.

Dennard’s girlfriend from high school (and eventual wife), Nadine, is Black, and has had a major influence on his life. Dennard was surrounded by racial diversity growing up and was just able to form a genuine bond with Banks, who was in a brand new situation entering college.

“Race wasn’t a thing for me,” Dennard said. “So when Gene and I hit it off, it was truly a bond of love, camaraderie and playfulness. We complemented each other.”

Banks and Dennard were immediately thrust into the starting lineup as the future of Foster’s program, a duo that just wanted to compete and win.

“We became so connected—kids from two different backgrounds,” Banks said. “I knew he had the same energy and the same feeling of wanting to win. Kenny fed into that and read that and that’s how we became connected. I love this guy almost close to more than life itself.”

'The original Brotherhood'

Once the upper level of Cameron Indoor Stadium started filling up for preseason open practices, it was clear that the 1977-78 season would be special for Duke. Along with the newcomers, Spanarkel returned after an all-conference campaign the year prior, as well as Gminski, the reigning ACC Rookie of the Year.

The Blue Devils went through growing pains to begin the season, but found their stride toward the end of the year, reaching as high as No. 7 and taking home an ACC championship. Though carrying the burden of youth, Duke rolled all the way to the NCAA Championship Game, ultimately falling to No. 1 Kentucky but gaining respect as “America’s team,” according to Banks.

“The things that I remember most [about the 1978 team] are the camaraderie and how that team grew together and became one big brotherhood,” Dennard said. “It was the original 'Brotherhood,' if you ask me, before Coach K.”

One of the lasting images from that season came after Duke’s closely-fought NCAA semifinal win against Notre Dame, when NBC’s cameras found Banks and Dennard sharing an emotional hug. The two kids from different worlds who just wanted to win were changing the landscape of Duke basketball.

While the Blue Devils failed to make the Final Four over Banks’ next three seasons, their star forward continued his upward trajectory. All-ACC performances in his sophomore and junior campaigns led to his lone season under Krzyzewski, during which Banks took home All-American honors as a senior and edged conference legends Ralph Sampson and James Worthy for the ACC scoring title.

Though a late-season wrist injury would take a hit to Banks’ NBA Draft stock, the San Antonio Spurs selected him with the 28th overall pick. In the state of college basketball today, a No. 1 overall recruit with similar success would be a surefire lottery pick after their freshman season, and, while that was extremely rare in the 70s and early 80s, Banks did think about leaving after his freshman and junior campaigns to start his professional career. Ultimately, he never seriously considered abandoning the fun he was having in school.

“I was not going to leave Duke,” Banks said. “I thought I made a commitment to finish this thing out and that was my main objective, let alone trying to get my degree as well.”

Today, we’ve seen how far the Duke program has come since first welcoming Claiborne, Banks and other Black pioneers. The 2020-21 squad has done everything from a Black Lives Matter protest to organizing an increased effort to vote. The Blue Devils will also have “Equality” written on the back of their uniforms throughout the season.

“I commend Coach K, I commend Nolan Smith and all the people involved,” Banks said. “I commend those players. It’s the most amazing thing from a high profile institution like Duke to make that stance. I’m almost in tears seeing that effort and that commitment.”

Before Duke’s run to the 1978 title game, the Blue Devils rarely found themselves on national television, but sending the program back into the sport’s spotlight allowed Black excellence in a Duke uniform to be seen on a national stage.

“TV was not yet big then. TV became big in the mid-80s with ESPN and that,” Krzyzewski said. “But it helped our university a lot during that time, just like the kids who have played for me once TV hit have helped this university in that regard with a number of African-American players that we’ve had who are amazing guys and outstanding players also.”

Banks remembers standing in front of the Duke Chapel before his career began, telling himself and his family that he would help Duke become a national power. Not only did Banks achieve that, but he also takes pride in the fact that the Blue Devils who followed him—such as Vince Taylor, Johnny Dawkins and Grant Hill—watched him play at Duke on TV and started taking an interest in their future home.

“With getting young Black men looking at [Duke] and saying, ‘If he can make it there then I can do it'—I’m very proud of that,” Banks said.

Blue Devil fans will be treated to another spectacle of freshman talent this year with Jalen Johnson, Jeremy Roach and company—young African Americans who will share the same floor as their pioneer "Tinkerbell" did 40 years ago.

Editor's note: This article is one of many in The Chronicle's men's basketball season preview. Find the rest here.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.