The gatekeeper of the Gothic Wonderland says that he is not a cat person—but he has taken in four stray cats and adopted two from a shelter.

The most recent was Summer Solstice Clabby Guttentag, a black eight-week-old kitten who walked into the garage on the morning of last year’s summer solstice. He offered the kitten a bowl of tuna and left for work, deciding that if he saw the little feline when he came home, he would welcome her into the family.

“I’ve had cats, but I’m not a cat person,” Guttentag said.

***

For 28 years, Christoph Guttentag, Duke’s dean of undergraduate admissions, has been responsible for materializing the dreams of just over 1,700 students who enroll as first-years at Duke each year, while disappointing the tens of thousands more who apply and don’t get in. The increase in applicants in past decades led to a dramatic drop in acceptance rate: Guttentag said that 30 years ago, 33.4% of applicants were accepted. Only 13% received good news in 2012. Since 2017, the undergraduate acceptance rate has remained under 10%.

As the country increasingly confronts the inequitable structures on which it stands, the questions of economic diversity, racial representation and preferences for legacy students in college admissions have taken center stage. Guttentag does not have answers to many of these questions, or he would not share them. Still, Guttentag’s office has been thinking about equity throughout the pandemic. Duke has made the admissions process test-optional this year, to help level the playing field for students with fewer resources.

And Guttentag has spent 50 to 100 hours since 1992 revising the denial letter to students (“two to three times more than I spend on the acceptance letter”) to soften the blow as best as he can. He is a bureaucrat who cares.

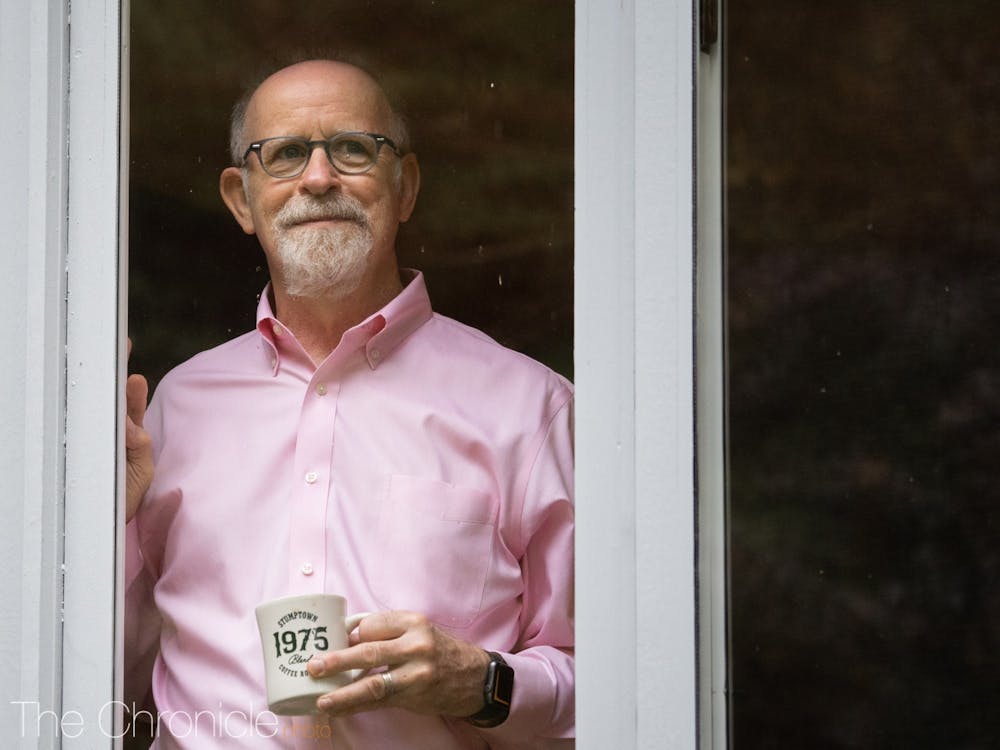

Admitting change

The dean was setting up the most elaborate breakfast I’ve had in months when I walked into his back patio to interview him. There were bagels, jam, whipped cream cheese, smoked salmon, capers, yogurt, blueberries, raspberries, moon drop grapes, warm milk, a kettle of coffee and four mugs (for the two of us). Guttentag’s wife, Cathy Clabby, who teaches journalism at Duke, had just returned from a morning run with friends and walked in at the same time as me. She told me later that day that she was also surprised and amused by the set-up, noting that the couple hadn’t had guests in months due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It must’ve been all the pent-up hosting,” she said.

The undergraduate admissions office is currently in what was once known as “travel season.” Students would visit Duke and envision their coming-of-age montage through campus tours and information sessions with admissions officers. Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, staffers have instead been going directly to high schools, discussing Duke on Zoom with interested applicants across the country. Guttentag has been speaking with students in Manhattan and part of the Bronx, the region whose 600 applications he personally reads.

A silver lining to the pandemic has been virtual recruitment, Guttentag said, which has allowed Duke to reach more diverse communities. Now that the barrier to entry is a Zoom link rather than a plane ticket or long car ride, rural and low-income students may be more likely to join. Guttentag said that the school will continue meeting with interested applicants via Zoom after the pandemic.

Guttentag personally reads applications from students in Manhattan and part of the Bronx, or about 600 applications a year.

With all the benefits of Zoom, however, Guttentag acknowledged that hosting students online is not the same.

“There’s a connection with others that can only be made in person, and I do miss that,” he said.

Coronavirus has affected more than the recruitment process in college admissions. In June, Duke announced that undergraduate applicants in the 2020-21 admission cycle do not have to submit SAT and ACT scores, citing difficulties registering for and taking the tests due to COVID-19, which may affect “those with the fewest resources,” Guttentag wrote in a news release.

But is test-optional actually test-optional? Or will this policy just benefit students with resources to submit decent scores during a pandemic? How does an application with an ACT score of 35 not look better than an application without any score?

I asked Guttentag those questions. He said that one way he plans to mitigate the risk of unintentional bias is ensuring that the percentage of accepted students who applied with test scores will roughly equal the percentage of students who applied without.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Although the admissions office is still working out the details of how the incoming class will be evaluated given a host of unprecedented factors—test-optional, limited extracurricular activities, academics affected by virtual learning—Guttentag made clear that test-optional is, in fact, test-optional.

“We want to be really careful that we don’t advantage students who submit test scores simply because they submitted them,” he said. “I’ve been explicit about this with my staff, and they understand it.”

***

Guttentag said that he “lays eyes on” 10% of admissions decisions every year. He chairs the overview committee, which meets after most decisions for the admission cycle have been made and discusses what more is needed to shape the incoming class. Senior staffers who favor particular students on the waitlist may present their applications to Guttentag for a second look.

The overview committee also adjusts decisions to reflect Duke’s goal of welcoming roughly 80% Trinity and 20% Pratt students in each class, Guttentag said.

Standardized testing aside, legacy preference is another aspect of college admissions that critics have claimed perpetuates generational inequality. 11% of the Class of 2024 are legacy students, Guttentag said. He did not answer when I asked whether legacy preference is fair (a word that he finds “unnecessarily reductive”), but he said that the University is continuing to examine its role in the admissions process.

In 2017, The New York Times reported that 19% of Duke students come from families in the top 1% of income in America (families who made about $630,000 or more per year), while 69% of students come from the top 20% (families who made around $110,000 or more per year).

Guttentag said that the wealth distribution of Duke students reflects that of the applicant pool.

“The college admissions process is not a level playing field,” he said.

***

In the two days after the serendipitous encounter on the summer solstice with its feline namesake, Guttentag bought Soli a bed and a toy that lights up and spins. He coaxed her into a cat carrier and took her to the vet for a check-up. He texted his son Eren nearly 10 photos of Soli eating, resting and playing.

Summer Solstice Clabby Guttentag walked into the family’s garage on the summer solstice last year.

Guttentag’s cosmic connection with cats started late in adulthood. In fact, his parents were not fond of pets and did not have any in the home. But cats find their way to Guttentag. The first was Artemis, whom he named after the Greek goddess of wild animals and hunting.

When Guttentag moved into his Chapel Hill home in 1993, a year after leaving his admissions job at the University of Pennsylvania, a “sort of brown and white” kitten wandered around his new house like an abandoned child. Guttentag didn’t want a pet in the home, but also wanted to make sure the cat was okay. So he fed her daily and assembled a shelter with towels and a cat carrier to keep her warm in the winter. Six months later, he relented and let Artemis in.

“At some point, I was just too smitten by it,” Guttentag said. “It was a gorgeous, well-tempered, interesting feline.”

I asked him again in our second meeting if he considers himself a cat person. He demurred.

“A cat person would have a better description of [Artemis’] color. A cat person would have a better description of her characteristics,” he said. “A cat person would have three cats.”

Saying no

Guttentag has spent a considerable amount of time coming to terms with the reality that part of his job involves disappointing an overwhelming number of people every year. For the Class of 2024, it was 36,726 students.

Unlike 20 years ago, when students and parents were much more likely to give angry calls or emails to the admissions office after being denied, applicants now react to rejections with less shock and more grace, Guttentag said.

“As we’ve become more selective, it’s not that people are less disappointed, but I think they’re less surprised if they’re not admitted,” he said.

Offering a glimpse of the past, Guttentag recalled a particular incident from “10 or 15 years ago.” He said that an Ohio family whose child was denied admission drove eight hours to Durham to plead their case. They arrived in the admissions office lobby unannounced and asked to speak with the dean.

In Guttentag’s office, the father argued that accepting his son would be a “win-win situation” for the student and the school, while the mother and child sat quietly on the couch. Guttentag said that he listened intently, but reiterated a few times that changing the decision was simply not an option. After the 30-minute conversation, he escorted the disappointed family back to the lobby.

“I felt bad for them, for the effort that they put in, to come all this way to get a result that was not what they wanted,” Guttentag said. “There just wasn’t a path for me to make a different decision because it would’ve undercut an entire process that at that point had made decisions on 25 or 30,000 students.”

But the dean of Duke undergraduate admissions is not immune to frustration amidst rejection either. Guttentag recalled feeling upset when Eren was not accepted to some of the schools that he applied to—more so than the actual applicant.

“In my heart of hearts, I was disappointed and a little bruised because I thought my kid was worthy, and at the same time, I had to go, ‘These are really hard schools to get into. They’re not going to admit everybody who’s a great candidate,’” he said. “And you know, that’s life.”

Eren, a senior studying physics and math at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said that he did not know his dad felt that way. He said that he applied to Duke, Stanford University, MIT, Harvey Mudd College and the California Institute of Technology. He was denied from Stanford and waitlisted at Harvey Mudd, and he received acceptances from the rest.

He said that he only applied to Stanford because “dad said I had to apply” and he would not have attended Harvey Mudd over the other schools, so he was “very satisfied” with the outcome of the application process.

“I’m very happy at MIT and I don’t think I’d be happy anywhere else,” Eren said.

But he wasn’t always happy. Eren said that he had trouble adjusting to college life in his first semester of freshman year and would occasionally call his dad between 1 and 3 a.m. when he felt the most homesick. Guttentag would tell his son what their cat Ariel had been up to (the family adopted her shortly after Artemis died) or that the crape myrtle tree in their backyard was finally blooming or that he and mom had just had a dinner party. Sometimes, he would just listen while his son cried.

Guttentag says he’s not a coffee aficionado. He does have 22 coffee makers, including 13 stovetop coffee makers, a French press, a French press for travel, a Chemex, a filter holder for pour overs, an Aeropress, a cold brew maker, a Krups automatic coffee maker, a Nespresso CitiZ and an ibrik for Turkish coffee.

Guttentag shows up for his son, even when he doesn’t know how. Eren said that when he came out to his parents as a trans man two years ago, they were surprised but made clear immediately that they would fully support his transition. Guttentag said he and his wife met with a therapist for about four months to process the change and learn how to best support their son. At times his dad was awkward, Eren said, but he surely tried.

“When I was a junior last year, my dad called me ‘junior’ as a nickname for a whole year, because I guess that’s what dads call their sons. He was like, ‘oh you’re a junior now, I can call you junior.’ And sometimes when we’re having a conversation he’d be like, ‘Let’s talk, man to man.’” Eren said. “It was kind of weird and kind of awkward but it was funny.”

A few weeks ago, Guttentag told Eren that he knew Massachusetts was getting cold so he would mail him his “MIT 2021” jacket and a pair of slippers. He also threw in a Durham mug as a little surprise.

“I miss Durham a lot, so he knew that that would make me happy,” Eren said.

***

Artemis is the cat that every cat after has been measured up against, Guttentag said.

Soli still falls short, he said. She won’t let you scratch her belly.

Guttentag’s son Eren said that Soli likes his mom and him, but that his dad is the indisputable favorite.

“My dad likes to act really grumpy about Soli and that she’s annoying him, even though he adores her,” Eren said.

Eren said that Soli likes him and his mom, but his dad is the indisputable favorite.

When Guttentag comes home from work, he lays down on his olive-colored sofa known in the family as “Mr. Green.” Soli sometimes senses this as an opportunity for attention, so she jumps onto Guttentag and lays down on his chest, stretching her arms into his beard.

Feeling safe, she eventually falls asleep.