Undergraduate students at Duke Kunshan University in China are contributing written and multimedia content to The Chronicle to be published every other Friday.

Editor’s note: This story contains a graphic description of an attack that was allegedly racially motivated. Reader discretion is advised.

*

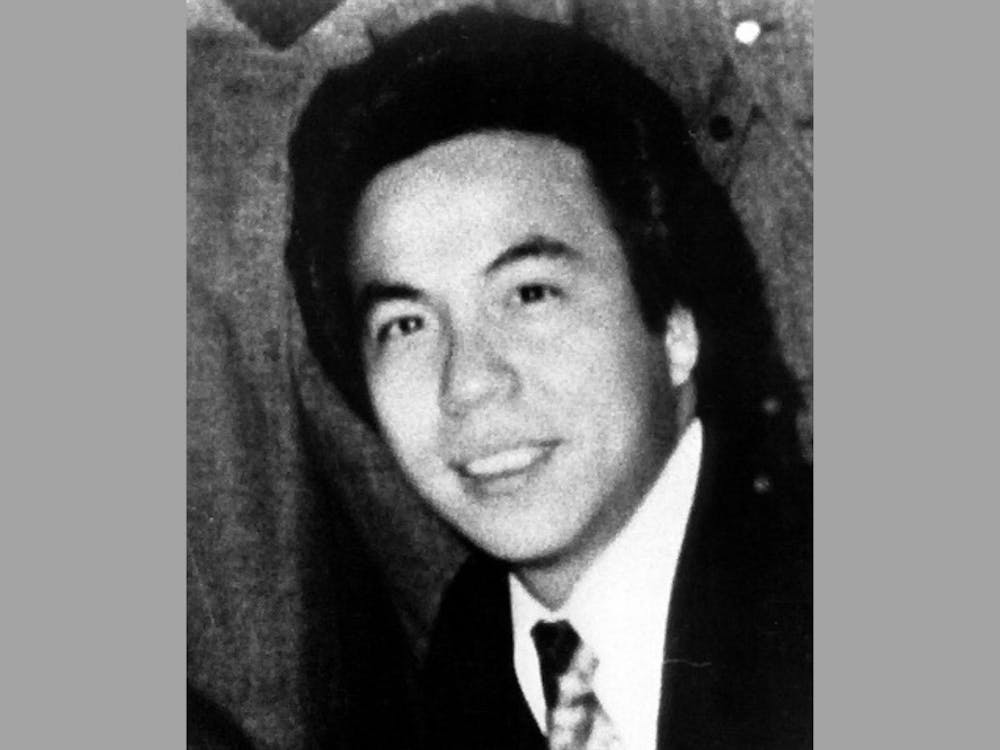

On June 19, 1982, 27-year-old Vincent Chin went out with his friends for a night on the town to celebrate his last few days as a bachelor. Born in Guangdong province, China and brought to the United States at age 6, he was by all accounts a hardworking, honest man, working at Efficient Engineering during the week and at a restaurant on the weekends. He was due to marry his girlfriend of three years, Vickie Wong, eight days later. But June 27 instead became the day that Chin was buried.

In 1970s Detroit, politicians and those in the auto industry scapegoated Japan, blaming competition from the burgeoning Japanese automobile industry for layoffs at auto plants and skyrocketing unemployment. On that June night, Chrysler employee Ronald Ebens and his stepson Michael Nitz, a recently laid-off autoworker, assumed Chin was Japanese and confronted him, allegedly shouting, “Because of you, little motherf******, we’re out of work,” along with racial slurs.

The encounter quickly became violent. Chin tried to fight back but was unable to defend himself. After Ebens struck him several times on the head with a baseball bat, Chin was rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead four days later.

Ebens and Nitz were convicted of manslaughter after initially being charged with second-degree murder. The final sentence issued by Judge Charles Kaufman? Three years probation and a fine of $3,000 each, with Kaufman saying, “I just didn't think that putting them in prison would do any good for them or for society… you don't make the punishment fit the crime; you make the punishment fit the criminal.”

Today, many Asian Americans consider this crime, and the injustice of the punishment, a catalyst in the emergence of the Asian American political consciousness and coordination of Asian American rights groups nationwide.

Chin’s story left an impact on me that I’ve never forgotten. It infuriated me that his assailants were only required to pay such a meager sum for taking a life in a country heralded for the fairness of its judicial system. But what left an indelible mark on me was the fact that he could be so easily “othered,” so easily considered an enemy to the country he called home, all on the whims of two fellow citizens who happened to look the part of an American.

As a Chinese American who lived in a predominantly white suburb for a majority of her life before attending college in China, I am no stranger to the feeling of being the perpetual “other.”

I still have vivid memories of elementary school when other kids would contort their faces or express disgust with the Chinese food that my grandma would lovingly pack for me each day. The sad truth is, when you’re met with, “Ew, are you eating rotten eggs?” in response to the tea eggs (茶叶蛋, a popular Chinese snack) you’ve brought for snack time, you learn not to bring such different food to school so as not to attract such negative attention. In high school, when you’re consistently confused for the three other Asian girls in your grade, it makes you wonder whether your personality and achievements are just that forgettable.

These are experiences all too common among Asian Americans, as well as people of Asian descent who have grown up in Western countries. Although it may seem trivial, you never forget the feeling of being the “other” and its propensity to cause you to reject aspects of your culture in favor of seeming “more American.”

Coming to terms with this feeling was one of the main reasons why I chose to attend Duke Kunshan University. I’d hoped that by learning more about the country of my grandparents’ birth, I’d be able to better navigate the discordance I’d felt between my Chinese heritage and American upbringing. With the greater understanding of Chinese culture and society that I have gained over the past two years, I now more than ever feel firmly grounded in the middle of two dominant countries that have increasingly been at odds in recent memory.

Even still, I am adamantly against the notion that Asian Americans should prove their “Americanness” in order to counter the recent COVID-19-related uptick in racist incidents.

Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post last month in which he effectively encouraged Asian Americans to prove how American they are by stepping up their acts of patriotism.

“We Asian Americans need to embrace and show our American-ness in ways we never have before,” Yang wrote. “We need to step up, help our neighbors, donate gear, vote, wear red, white and blue, volunteer, fund aid organizations and do everything in our power to accelerate the end of this crisis. We should show without a shadow of a doubt that we are Americans who will do our part for our country in this time of need.”

My question to Yang is: How much more American did Chin need to be in order to avoid being killed by two men who allegedly wrongly assumed his ethnicity and scapegoated him as the cause of their economic losses?

How much more American did the victims of racist attacks, spurred by COVID-19, need to be to avoid being characterized as vectors of the virus?

If there’s anything we Asian Americans should take away from Vincent Chin’s story, it’s that nothing about one’s perceived “Americanness” will stop those seeking to scapegoat a marginalized group that appears to be the source of their frustration. Instead of conceding aspects of our cultural backgrounds, insisting that we are “American enough,” and hoping that we’ve shown enough patriotism to be spared racial abuse, we must resist external pressure that tells us we cannot have hybrid cultural identities. We must be prepared to address the racism at its root, holding accountable those who perpetrate racial attacks and those who perpetuate such divisive attitudes. We must not forget the injustice of Chin’s story and allow his suffering to be in vain.

Samantha Tsang is a junior in the first-ever graduating class of the Duke Kunshan campus’s undergraduate program, located outside Shanghai, China.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.