Until Duke canceled in-person classes because of the coronavirus pandemic, one food service worker clocked in for up to 40 hours a week at one on-campus dining location and 20 hours at another, both on West Campus.

Now, after being laid off from both locations following the closure of campus, she said she gets no pay and no benefits because she is considered a “part-time” contract worker, not a Duke employee. She has struggled to pay her bills and has had to move in with her family to get by. She asked to remain anonymous in this article for fear of retribution.

But this worker and other contract workers—the vast majority of Duke’s food service workers—would still be getting paid if they worked on East Campus, just over a mile away. There, food service workers at Marketplace, officially Duke employees, will be fully paid and receive their usual benefits through May 31 despite being off work for many weeks, according to Charles Gooch, former president of Local 77, the union representing housekeeping and Marketplace employees.

The coronavirus pandemic has illuminated a dual system of rights for food service workers doing similar work on Duke’s campus, a system that has grown more unequal over the last decade, as the Brodhead Center replaced Duke’s dining hall in 2016 with various restaurant offerings.

For many years, workers in the old West Union, then known as “The Great Hall,” were still technically Duke employees, though they worked for private management companies, Gooch said. So, according to Gooch, they got benefits. Now contract workers make and serve the food at Brodhead Center dining locations, and some don’t receive benefits like health insurance or even sick time because they have bosses other than Duke.

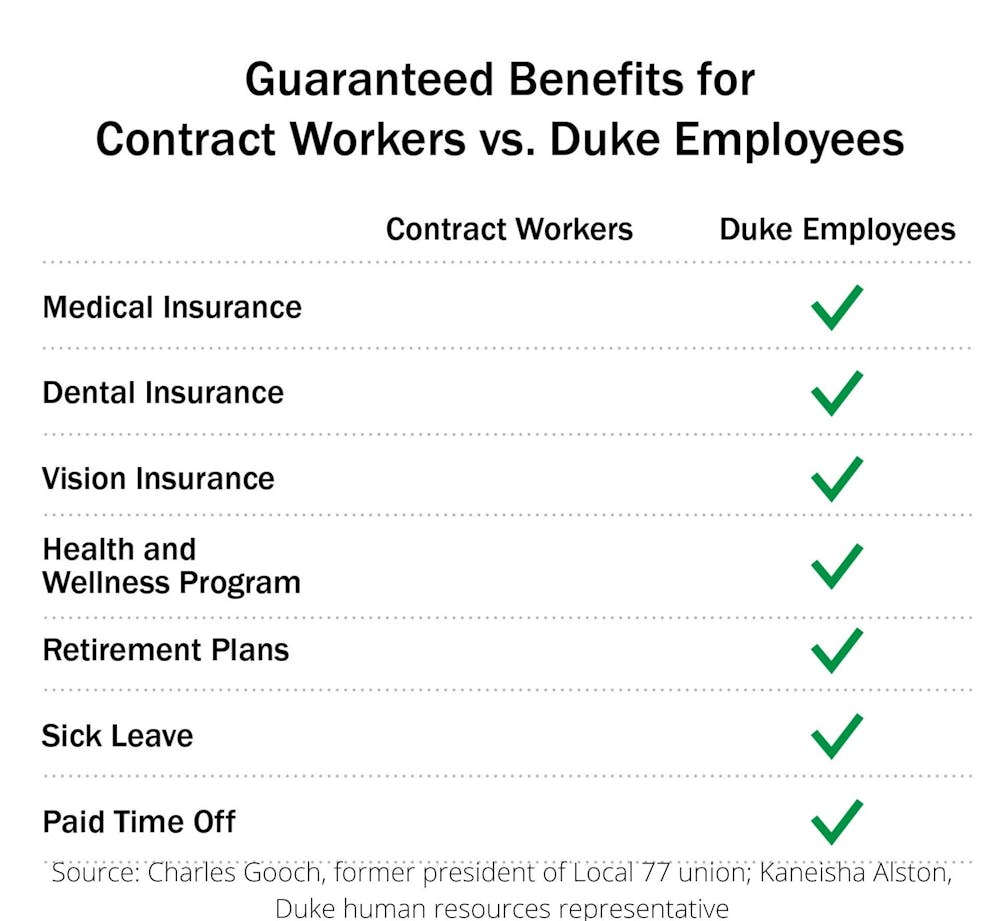

Contract workers who don’t work “full time” aren’t guaranteed pay under Duke’s COVID-19 response, said Executive Vice President Tallman Trask. Even before the pandemic, they weren’t guaranteed any benefits, even if they were full-time workers, said Kaneisha Alston, a Duke human resources representative.

To the laid-off contract worker, that doesn’t seem right.

“There’s an unfair disadvantage for contract workers who come to work every day at Duke,” she said. “Knowing that this is a billion-dollar school… it hurts knowing that they could be doing more for contract workers.”

Overall, Trask thinks the contract worker system has been overwhelmingly positive, with no significant downside, because it allows for more than a dozen different food options and supports local vendors.

“There really haven’t been any [negatives],” he said.

‘Really unfair’: Contract workers aren't guaranteed benefits, and many aren’t guaranteed pay during the pandemic

About 375 of Duke’s food service workers are contract workers employed by outside companies, according to Robert Coffey, executive director of dining services. By contrast, Coffey said, Duke employs 70 food service workers who belong to the Local 77 union.

Trask said that Duke encourages the contracting employers to provide similar benefits to those offered by the University, and that full-time contract workers get “all the normal health benefits, or a version thereof.”

But that’s really up to the individual vendor or restaurant owner. The Chronicle reached out multiple times to the owners of more than 10 on-campus eateries with contract workers to ask what benefits they gave their workers. None responded. Coffey declined to list what benefits they get, saying Duke can’t “publicly share confidential independent vendor human resource or financial information.”

Only Duke employees and full-time contract workers—200 of the 375—are covered by Duke’s $15 minimum wage, which went into effect in 2019, according to a news release. Duke “struggled” to push employers to pay all their workers at least $15 per hour, Trask said, but a $15 minimum wage for contract workers is “essentially in effect.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Initially, it was unclear whether food service workers would get paid at all after Duke moved spring semester classes online March 13.

After some pushback from activists, Trask wrote in a March 18 letter to students that all “full-time” contract workers would be guaranteed pay through May 31.

“We had to close down pretty quickly, and we wanted to protect employees,” Trask told The Chronicle. “A lot of those contractors look to everyone as if they were full employees, so it seemed like the admirable thing to do.”

But Trask’s letter did not protect the remaining 175 “part-time” contract workers who may have had their hours cut or been laid off following the shutdown. Trask explained the lack of protection by saying that the University did not cover many other part-time employees.

Despite the many hours she worked, the anonymous contract worker was considered a “part-time” worker. She said this is because before she was laid off, she helped cover some shifts at an off-campus affiliate while also working on campus, she said. She said she never got any other benefits from the dining location while she worked there.

Some employees are working limited hours at an off-campus affiliate of one dining location, but she isn’t one of them. She used to be paid $15 per hour, but is now getting nothing from her employer or Duke.

Now, she is struggling to keep up on bills. She still hasn’t received unemployment benefits, and she spent her federal stimulus check on rent in April. She now has no way to pay rent and is struggling with other bills, she said.

“As a contract worker, you definitely feel like an outcast,” she said.

Another on-campus contract worker has had a similar experience. She also wished to remain anonymous in this article for fear of retribution.

This second contract worker used to work 40 hours a week at an on-campus dining location, but now she works just 20 hours a week at an off-campus affiliate location and struggles to make ends meet. She said she never got any basic benefits from the job.

With her hours cut in half, her other source of income, a small business, has also been slashed almost entirely because of Durham’s stay-at-home order. She hasn’t cashed her stimulus check yet, because of the uncertainty going forward.

“If it wasn’t for my savings, I wouldn’t be able to get by right now,” she said. “I was using my savings to buy a car, but now I have to use my savings to buy food.”

Trask did not respond to multiple requests for comment when asked if workers like the two in this story should be deemed full time.

Without a union, contract workers don’t know who to turn to for help, Gooch said. Some have organized along with other workers demanding pay.

Chris Huebner, a third-year English Ph.D. candidate and member of the Duke Graduate Students Union, has pushed for Duke to guarantee full pay for all contract workers, publishing a list demands in The Chronicle April 13.

“This is a really unfair way of treating people,” Huebner said.

Duke Contract Workers United and other organizations published a similar set of demands March 31.

Trask said that activists’ pressure in the form of a list of demands published March 17 in The Chronicle played no role in his decision to ensure pay for full-time contract workers.

“They sent me 100 copies of the [demand letter] but it didn’t help,” Trask said.

Even Duke-employed food service workers face an uncertain future

The perks of being a Duke-employed food service worker include health insurance with a $20 co-pay, vision and dental insurance, access to a health and wellness program, a retirement plan and sick leave, according to Gooch.

Duke employees also are receiving paid time off with benefits guaranteed from at least March 24 to May 31, Gooch said.

These workers, however, face tremendous uncertainty going forward.

Duke hasn’t said if its food service employees will continue to be paid after May 31, when, according to Trask, hours are traditionally cut because of decreased student traffic in the summer. In addition, Local 77’s contract is set to expire June 30, leaving Gooch fearing Duke could cut back on benefits for union workers, and perhaps lay some off.

Trask told The Chronicle that the University is currently in negotiations with the union and says not to expect “major changes.”

“I hope he keeps his word,” Gooch said.

But like many others during the pandemic, Duke is facing financial issues that could leave it hurting more than it did during the 2008 financial crisis, Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations, told The Chronicle in early April. In April, the University began a hiring freeze for nonessential employees, and put most raises on hold starting July 1. Duke announced last week that it would suspend University-paid contributions to a retirement plan for faculty and staff and cut salaries for highly compensated employees for the next 12 months.

It will be a tough job market for contract workers, Gooch fears. In North Carolina, more than a million people have filed for unemployment since March 15.

“This is worse than the Great Depression. The poor people will pay for this after all this happens,” Gooch said. “They’re going to cut jobs.”

Managing Editor 2018-19, 2019-2020 Features & Investigations Editor

A member of the class of 2020 hailing from San Mateo, Calif., Ben is The Chronicle's Towerview Editor and Investigations Editor. Outside of the Chronicle, he is a public policy major working towards a journalism certificate, has interned at the Tampa Bay Times and NBC News and frequents Pitchforks.