Editor’s Note: This story was reported and written in Spring 2019. It is being released now as part of our series about the wealth gap at Duke.

What does it mean to be a first-generation, low-income student at Duke? Many feel anomalous, hidden and two steps behind. But more overwhelmingly, members of the first-generation, low-income community say they are tenacious, deserving and proud of their identity.

Duke’s Class of 2021 and Class of 2022 are composed of 12% and 9% first-generation students, respectively, according to the class profiles released by the University. These numbers may be surprising, as the first-generation identity is not always visible.

Duke defines first-generation as “any student who does not have any parent with a 4-year degree,” according to an email from Alison Rabil, assistant vice provost and director of the Karsh Office of Undergraduate Financial Support.

The Duke student body is also relatively wealthy, according to The New York Times, with 19% of students coming from the top 1% of families in terms of income and just 3.9% coming from the bottom 20%.

The Chronicle interviewed a few students who identify as first-generation and low-income in an attempt to better understand and bring to light these identities.

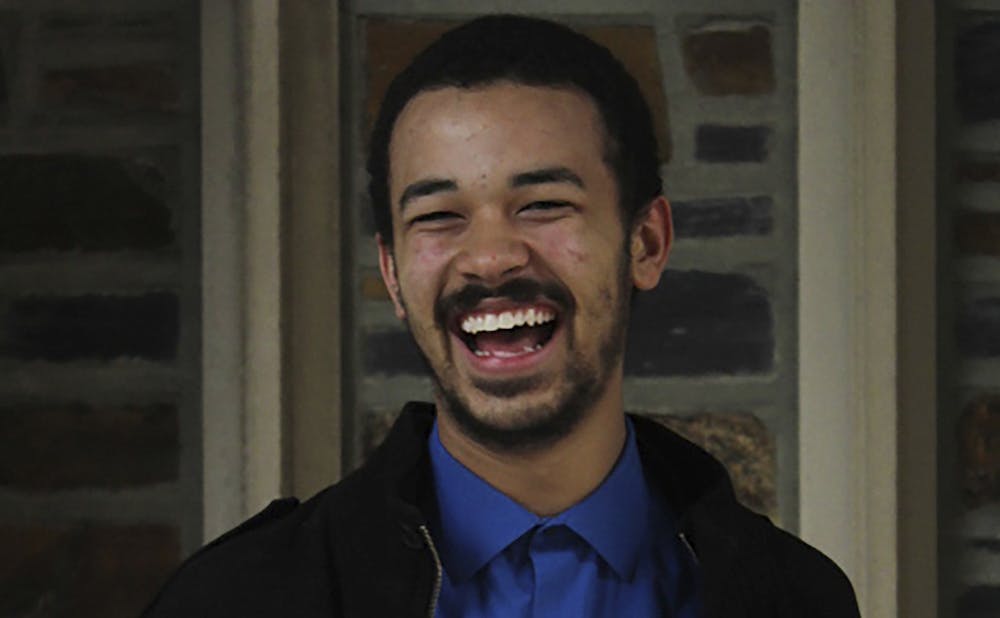

Each student’s story and experience of being a first-generation, low-income student is different. They are not a monolithic group, as junior Jamal Burns, co-president of Duke Low-Income, First-Generation Engagement (LIFE) put it. The first-generation and low-income identities are distinct, so identifying with one does not necessarily mean identifying with the other. Many, but not all, first-generation students come from low-income families and low-resourced schools, and these identities often reinforce one another.

Navigating the journey alone

The challenges for first-generation students arise long before they step foot on campus. For some students, attending college is a given, with their sights on a school since day one. For others, the prospects of college are not as simple. Many first-generation students were forced to learn how to navigate the application process on their own, adding greater burden to the already harrowing process.

Burns had to turn to Google to help him understand the complex college application process.

“My high school counselor didn’t know what the Common Application was,” Burns said. “That initial shock value of really genuinely having to learn everything by myself—like look up colleges, what Early Decision meant or what Regular Decision meant—is something I know other students did not have to face.”

Paula Ajumobi, Trinity ‘19, attended a private high school on scholarship, and unlike Burns, she said her college counselor was helpful for her. Yet Ajumobi still relied on her own online research to decide where to apply. After hearing that one of her peers applied to Duke, she also decided to apply on a whim.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” Ajumobi said, “so if I had no idea, I might as well apply anywhere and everywhere that accepts my fee waiver, right?”

Without the financial security to know that she could afford college, Ajumobi did not apply Early Decision to any school. Instead, she said that she applied to whichever schools gave the most financial aid.

She noted that for some students, financial aid was never a factor when applying, given that approximately half of undergraduates applied Early Decision and about 52% of undergraduates receive financial aid at Duke.

Senior Ibrahim Butt, who is co-president of Duke LIFE and was recently elected undergraduate Young Trustee, faced an even greater burden as an international student from the United Kingdom. He was part of a first-generation, low-income scholarship in the United Kingdom called the Sutton Trust.

After first learning about the ACT in April, Butt ferociously prepared to take the unfamiliar test in June. He was balancing two jobs, studying for his U.K. exams and prepping for the ACT at the same time.

Because the ACT is only offered in select locations in the United Kingdom, Butt had to travel three hours by train and stay overnight to take the test. The total cost would add up to 500 pounds. Because he was unsatisfied with his first score, he worked the entire summer to afford to take the test again.

‘I am an anomaly’

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Before arriving at Duke, some students were unaware of how significant their first-generation, low-income identity would become once they got onto campus.

“Getting here, you realize this institution isn’t set up for you,” Burns said. “People get in for different reasons, and some people have lives that are more beneficial to getting in than you did. Just because we all go here, I was under the impression we would all be on the same footing, but it’s just definitely not the case.”

This realization that Duke is not quite what it seems started with the stark wealth disparity the students felt on campus from day one.

When Burns was moving in to East Campus, First-Year Advisory Counselors greeted him excitedly and helped him move his luggage—two suitcases. As the FACs moved his belongings, Burns said one FAC told him that “we like residents like you” because “you don’t have many things.”

However, Burns had brought everything he owned in those two suitcases. He said he felt taken aback and minimized by the comment.

Butt also came to Duke with two suitcases during international student orientation, “wide-eyed and not ready for it.” Although he set aside extra expenses to settle in, he did not realize how expensive moving in would be. He used the free Target trip sponsored by Duke, emphasizing that he had to buy the bare minimum and still does.

These experiences were just the beginning of the financial burdens.

For Sloan Talbot, Trinity ‘19, the first thing she worried about on campus was not trying to enjoy orientation week or partying, but finding a job and figuring out how to use dining points efficiently. Budgeting laundry, navigating student health care and finding affordable summer storage were all challenges she was not prepared for.

She also did not realize the amount of money that went into the social aspects of college. As a first-year, when everyone is trying to integrate, not having the money to dine off campus or attend social gatherings can make it hard to fit in. These discrepancies only work to reinforce the low-income identity, Talbot said.

“I didn’t know that, when I was going to get to this top university, there was going to be such a big income gap between people,” Butt said. “When you realize how wealthy some of your peers are, and some of the resources they can tap into versus what you can tap into, it just cemented my [first generation, low-income] identity that I am an anomaly on this campus.”

Carving their own path

Besides the income disparity, the students also noticed they came into college with a more limited idea of how to navigate college life. They often lacked the initial academic and social guidance that non-first-generation students receive from their siblings and parents.

“Part of the struggle of being first-generation, low-income is that you either have the information but you don’t have the resources, or you don’t have either the resources nor the information,” Talbot said.

Even with supportive parents, first-generation students often have to navigate college spaces independently. Parents can give you well wishes and emotional support, she said, but you also need someone who has been through the academic environment to help you through that space.

Butt found himself with a difficult first semester schedule, later realizing that his peers took easier classes as advised by their parents or siblings. However, his parents did not know about required classes, what a dining plan is or why you need an internship over the summer.

“These basic, fundamental ideas, they don’t know and they still don’t know,” Butt said. “I feel that there’s such a disconnect between my life here, and what I go through here, and what my parents know about my U.S. university experience.”

Butt said his parents are supportive, asking him to come home during the summers, but they do not understand the importance of internships in order to be competitive—and the way you can still feel behind, even if you’re attending a top university.

Ajumobi described a similar kind of experience. Coming in, she was surprised by how much people already seemed to know about what classes to take and with what professors.

“[College] was already predestined for a lot of people, and here I was just trying to navigate being first-generation—navigate what college meant to my family because my mom didn’t understand what college meant, my sisters didn’t understand what college meant,” Ajumobi said.

Academically, Burns said it was intense coming into an environment that was drastically different from where he came from. In his high school, he did not have to write more than a five-page paper.

Particularly, Burns said his science classes are often designed for people who already have a strong background in science, especially in introductory biology. On the other hand, he said the chemistry department has done a good job providing different levels of classes for students with different backgrounds. Chemistry 99D, an introductory course intended for students with a limited background in the field, was the reason he was able to and is interested in taking chemistry through organic chemistry.

Without having parents understanding the ins and outs of college, figuring out how to find academic support is difficult. Butt said he didn’t learn about office hours until late first semester, and always having done things independently, asking for help and talking to professors was a scary feat.

Talbot said she was “intimidated” by professors who had strong academic backgrounds, and she did not know how to connect with them

“I think, being [first-generation], unless you have someone coaching you into those spaces, it’s really hard to get there organically,” she said

Talbot also said she didn’t realize the rigor of networking or the need for research early on—she didn’t know these were even options for first-years. Even when considering post-graduation options, she noted that first-generation students often don’t pursue certain opportunities because of a lack of awareness and availability.

Given these challenges, first-generation students have to pave their own path, Ajumobi said.

“[I realized] this place wasn’t meant for people like me, and I have to create my own space here where I can succeed,” Ajumobi said.

‘Disturbing’ amount of pressure

Along with the pride of being first-generation is the pressure of being the first in the family to graduate from college. The considerations of each decision they make often have far-reaching impacts.

“You’re thinking about not just your job, but your entire community back home—the community that propelled you to this point,” Burns said. “It’s not just ‘I want to make my parents proud,’ it’s that I have to be the modem for social mobility. And if I’m not, then I’ve completely failed.”

With each action, decision and dollar spent, Burns said he has to consider how it will affect his community back home. On top of that, the expectation to find a stable, high-paying job to support both yourself and your family may clash with a personal interest in a less-lucrative field.

Duke LIFE helped host, in 2019, the first regional conference at Duke focusing on first-generation and low-income college students. In collaboration with EdMobilizer, an organization that advocates for first-generation and low-income college students and alumni, the conference brought in around 100 students from private, public and community colleges in the South. The theme of the conference was “Next Generation Leaders: Preparing for Our Futures While Leaving an Impact for Those to Come.”

Talbot explained that many first-generation, low-income students come from rural areas, so they discussed what it means to return home and contribute to your town.

“You’re always going to have this [first-generation] identity, but now you’re someone in your family who has this degree—this piece of paper—that no one else has,” Talbot said. “That for society means a lot, but what does that mean for us as [first-generation] people ourselves and our families, and what does it mean to give back to our communities.”

Talbot said she has friends in the first-generation, low-income community who have made decisions for financial stability, but her passion in public interest and academia are less stable and clear-cut than other careers.

Talbot has questioned whether she should have chosen a route with greater financial security, particularly during her first and second years. However, her mentors guided her to continue on the road less traveled. Without them, she said she might have gone on a very different track.

Even after graduation, the path of first-generation, low-income students is unclear because they are facing “a new frontier,” Talbot said.

Ibrahim Butt is, with Burns, co-president of Duke Low-Income, First-Generation Engagement.

Butt also knows many first-generation, low-income students who put their desire to attend graduate school on hold, and they instead take high-paying jobs in finance or consulting right out of college. Although their interests may not lie in these fields, they need the money to send home, pay off loans or save for their later career, Butt said.

“We want to drag our parents out of the low socioeconomic status that they’re currently in, so that they’re comfortable later on,” Butt said. “We’re not only worrying about ourselves, we’re worrying about our parents. It’s disturbing, the pressure that’s on us to get a high-paying job after we graduate.”

‘A label that we’re proud of’

Unlike race or gender, the first-generation identity is invisible. Among Duke’s student body, about one in 10 people will identify as first-generation, an identity that crosses racial, economic and geographic lines.

“I think being at such a space of privilege like Duke, a lot of people assume you come from the same cut of cloth,” Talbot said. “I just think being more sensitive to class issues is really important, but also not to misconstrue or to put labels on people before they share them with you is really important.”

The students interviewed want the administration and student body to have a greater awareness and understanding of the first-generation identity and of the vast income disparity at Duke. They want peers to know how hard some first-generation students worked to get here and the many barriers they face. They want others to know that being wealthy is not normal to them.

Specifically, they want empathy for the first-generation experience.

Many of the first-generation students interviewed were afraid to reveal this identity during their first year at Duke, unsure of what it meant and how others would react. It is painful to hear the negative reactions students experience after disclosing their first-generation identity, which Ajumobi noted often happens in professional spaces.

When someone says they are first-generation, students should be aware of their actions, questions and tone of voice, Ajumobi said. It’s good to be curious, but not patronizing—treat people as your equals and be appreciative, she explained.

However, most of all, they wanted people to know that first-generation students are here because they deserve to be here. They are not here because they are first-generation—they worked just as hard and are more than capable.

“First-generation students exist, and we want to be recognized as such, because it’s not a label that is damaging, it’s a label that we’re proud of,” Burns said.

‘We exist on this campus’

Talbot said she did not know she was first-generation until she was invited to the first-generation pre-orientation, which started two days before official move-in day. Although she appreciated the orientation, she said there was nothing holding the first-generation community together afterward.

In Fall 2018, Duke LIFE became the first student organization dedicated to these identities. Duke LIFE works with the Office of Undergraduate Education to host events and programs to support first-generation, low-income students.

The student group’s goals are community building, advocacy in administrative spaces, engagement with the broader Duke community and recognizing the importance and vitality of these identities. Anyone who identifies as first-generation or low-income can join.

The group was founded out of a need for the awareness and visibility of first-generation, low-income students on campus. By working with the administration and increasing institutional awareness, Butt is hoping for greater consideration of these identities when rolling out new policies and programs.

“We’re there to work with the administration, but also pressure the administration,” Butt said. “We’re not just going to rubberstamp what the administration does, we’re really going to ensure that [first-generation, low-income] students’ perspectives are at the highest echelon of this university.”

The same semester Duke LIFE was founded, Duke wrote in a letter to some families that it would stop paying for student health insurance for students on financial aid whose calculated parent contribution is greater than $0. President Vincent Price later announced that the changes would no longer be implemented, following student resistance.

Burns said that greater low-income, first-generation representation on Duke’s decision-making bodies would have prevented rulings like these, which disproportionately burden low-income students, from being made.

Jamal Burns is, with Butt, co-president of Duke Low-Income, First-Generation Engagement.

Besides policy, the students felt that having this organization is important for creating a support structure and community that lets students know they’re not alone. The space allows students to talk about the first-generation, low-income experience with others who understand.

“I think a lot of the struggles of being first-generation is the feeling of ‘do I fit in,’ and the answer is always an absolute yes,” Talbot said. “I think that’s something that every first-generation student faces, especially at a place like Duke, do I fit in in these spaces.”

A long way to go

Duke LIFE did not exist when Ajumobi was a first-year, but she wishes it had. First-generation student groups have been around since 2016 at peer institutions like University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University, while University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s group dates back to 2008.

Duke has a long way to go, Butt said, but he’s hopeful Duke LIFE can help the University improve. The organization is working toward getting their own space on West Campus, increasing the income cutoff for full-ride financial aid to $100,000 and expanding the David M. Rubenstein Scholars program to all students qualifying for full-ride financial aid.

The Rubenstein Scholarship provides financial, academic, personal and professional resources to around total 170 selected first-generation, low-income undergraduates. Established in 2016, the scholarship is an important step in visibility and value on campus, Talbot said.

Even though there is currently no plan to expand the program, Sachelle Ford, director of Duke LIFE and Rubenstein Scholars, said that Duke is need-blind and covers 100% of demonstrated need. She hopes to create more coordinated efforts around campus to provide comprehensive support for all first-generation, low-income students.

“My goal is for first-generation and low-income students to have the same access to the University’s resources and opportunities as their upper-income and continuing-generation peers,” Ford said. “To do this, we have to recognize that sometimes we make assumptions about knowledge that all students have—and those assumptions aren’t true.”

She hopes to close the information and access gap at Duke, helping students be competitive in awards and internships. This responsibility is not just on the students, but also the instructors, she said.

“As administrators and faculty, we need to make our expectations clearer,” Ford said. “We need to give the students the space to tell us and show us where they are so we can meet them there.”

Duke LIFE is also hoping for summer funding and career-oriented resources dedicated to first-generation, low-income students, as well as a robust first-generation faculty and alumni association. They are optimistic that their efforts to increase visibility and advocate for improved policies will propel Duke in the right direction.

“I submitted the name LIFE, and I did that because I want people to know that we have lives here. We exist on this campus, and our life at Duke is shaped and centered around these identities,” Burns said. “We are tenacious. We are here.”

This article is part of the wealth gap series. We are exploring how wealth impacts the student experience. Read about the project and the rest of the series.