Nothing comforts me more than marking time. I love routine, love the assurance of waking up at the same time every day. I love looking through a calendar with certainty. It will always go like this: Thanksgiving, Advent, Christmas, New Year’s. After forty days of wintery Lent will always come Easter. Every year, no matter what. Like clockwork.

I had just turned ten years old, already a child in love with routine, when I found out I had scoliosis. I began wearing a corrective back brace at the end of April that year, around Easter. I marked each grim anniversary impatiently: 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013. Easter would roll around again, and I’d think to myself this has to be the last Easter I spend in this back brace.

Finally, in 2014, it was. But all too soon, I got a new date: July 21, 2015, the day I had the surgery you have when the back brace doesn’t work. I then spent the first anniversary after my surgery, in 2016, recovering from a second, unplanned surgery to correct something that went wrong in the first.

That year had been full of a new kind of pain, pain that made me scream the first time I felt it. On that first anniversary, I hoped that I was finally beyond this ordeal. I had a new date in mind.

August 23, 2016: I marked it on my wall calendar, after weeks of scribbled-in physical therapy and doctor’s appointments. I wrote “DUKE” in huge blue letters on move-in day and drew a thick arrow across each of the remaining days of August and into September, then all the way off the page. My back was fixed, and the pain would surely subside soon. I was a Duke student now.

I left that calendar on the wall, smiling at it every time I went to sleep in my childhood bedroom for the next three years. I thought I’d find the end of that long arrow when I’d arrive home with a full minivan and go to sleep in this room, tired and happy and newly-graduated on May 11, 2020.

When I learned that I’d never go back to college, never find the end of that arrow I drew back in 2016, I took the calendar and all the pictures from high school off my wall. Each one was like a time capsule from long ago, full of the faces of strangers.

But the Liddy in those pictures–the Liddy with long hair and square glasses who thought that her pain was temporary–she is a stranger, now, too.

My paternal grandmother, Gigi, had a habit of saying, in her thick upstate South Carolina accent, “I keep waking up!” My siblings and I thought it was very morbid. “Of course you keep waking up, Gigi.”

Except one day she didn’t. August 23, 2019: exactly three years after I’d moved into Duke for the first time, three days after I’d moved into Duke for the last time. It had been the hardest summer of my life, and it ended with me holding my dying grandmother’s hand. My dear friends picked me up from the airport a few days later in the pouring rain, dropping me off in the Keohane fire lane with my suitcase.

The elevator was out of order, and by the time I scaled the five flights of stairs to the sixth floor, I was sobbing. How could the damn elevator break during move-in and why did Gigi just die and why does my back hurt so damn bad just from carrying a stupid suitcase and how am I going to be in pain for the rest of my life.

Weeping in the hallway, with the parents of my new neighbors eyeing me worriedly, my mind traveled back to a few months before, to the newest addition to my timeline.

April 19, 2019: Good Friday, two days before Easter Sunday, eleven years after all this began. My best friend and I sat in a windowless room in the maze of Duke hospital, and my new doctor told me that I’d be in pain for the rest of my life.

There is no other date to mark, no magical treatment or cure. I will wake up in pain every day that I wake up. I have to find out how.

Now, a year after I lost the illusion that I’d ever have a future without pain, I am living with the loss of another future. My early twenties will be defined by a virus. The most bitter parts of myself are angry that, after working for a year toward accepting a future more painful than I could imagine, here was the future, altered again: weeks of rest and celebration gone, routines bashed, freedom curtailed, fear magnified. My carefully-planned timeline dissolved.

But I am not alone this time. I’m grieving this lost future with so many people, and it feels eerily familiar. I’ve seen these feelings before: the disappointment, the dread, the rage, the sadness, the exhaustion, the grief. I’ve been learning for a year, really for my whole life, where to find hope and purpose and comfort and connection in deep pain, how to keep marking time when the idea of living another day sounds excruciating.

The versions of ourselves that will exist a year from now will likely think, if only they knew what they were in for. But that’s the point, right? We don’t know.

I couldn’t tell Liddy from a year ago how this year would be the hardest of her life. I wouldn’t want to tell her, anyway. Anticipating pain makes it worse: that’s why the doctor asks you about how school’s going before she resets your broken bone. It’s better if you don’t see it coming, don’t tense up, don’t start feeling it before it happens.

On April 19, 2020, I went for a run. I never thought I could. I always had to sit in the bleachers reading during gym class while everyone else ran around: the one and only perk of a back brace. Every step, every minute, every breath is a little victory, not because I somehow conquered pain, but because I am doing what felt impossible at my lowest points over the past year. I know now that I can live with pain. I learned that the only way I could learn it: by living.

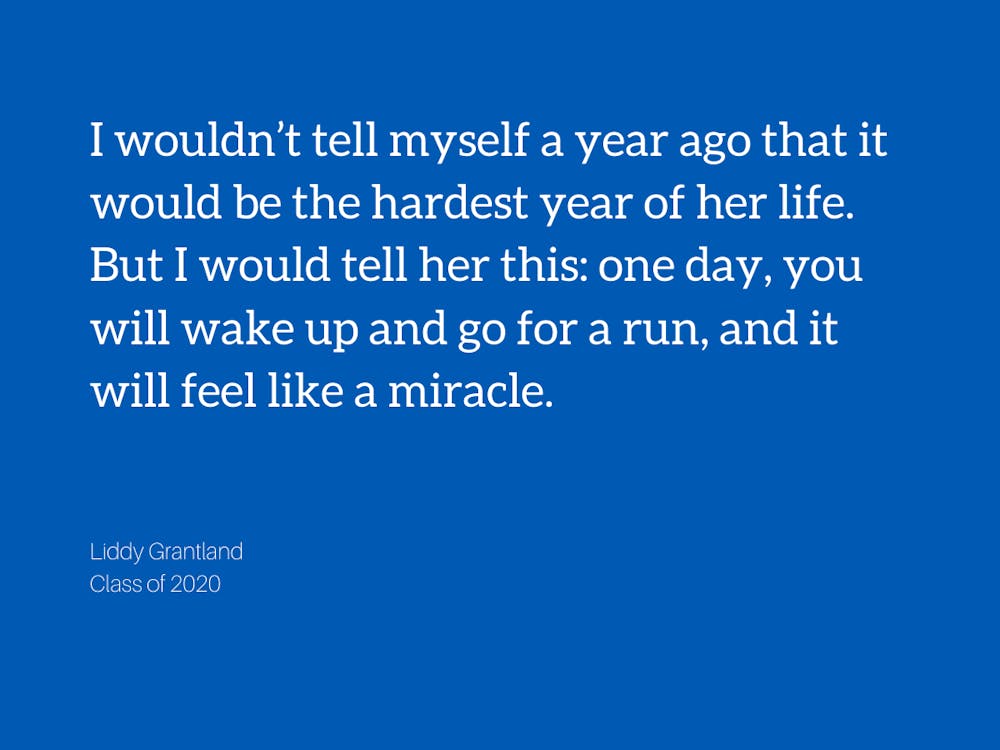

I wouldn’t tell myself a year ago that it would be the hardest year of her life. But I would tell her this: one day, you will wake up and go for a run, and it will feel like a miracle.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

The endless tears of grief will happen alongside the anxious-happy-nervous tears before a big, happy moment, the relieved-joyful-hopeful tears of knowing the next thing to do, the tears of laughing so hard at the silliest things.The tight, painful breaths of the days where the hurt is acute will happen, but so will the easy, gentle breaths of rest, the deep, cleansing breaths of calm, the tired, happy breaths of running when you never thought you could. The nights where pain and fear and anxiety keep you awake will happen alongside the nights you go to sleep dreaming of a hopeful future: a bed with soft sheets where you and the person you love sleep peacefully side by side. A house with plenty of sunny windows and exclusively comfortable chairs and a garden in the backyard.

But what will really save you, what will keep you alive, will be the people who are willing to carry your pain alongside their pain. They will hold you hand, will ask if you’ve eaten, will sit on the edge of your bed and talk for hours, will drive you home from the airport in the rain, will yell at you when they find out you carried your suitcase up the stairs instead of calling them for help.

You will sometimes feel exhausted at the very idea of living, of moving forward, of marking the days as they pass. But you will live anyway.

You will just keep waking up.

Liddy Grantland is a Trinity senior who highly recommends listening to “It’s Raining Men” on a loop for the entirety of a run. There is simply no other way. Her column, feel your feelings, runs on alternate Tuesdays.