After hours of waiting for the results in my home state’s elections, one thing is certain: Iowa’s beloved yet unconventional voting process is under siege.

As one of Duke’s few Iowans, I’m here to defend our first-in-the-nation caucuses.

For the uninitiated, Iowans don’t cast primary ballots in February. Instead, they vote with their feet. Across the state, friends and neighbors gather together and physically stand in their candidate’s corner. It’s what I fondly call “politics in action.”

The caucuses spawn a brand of citizen democracy rarely found in today’s digital age. If a candidate hopes to win support in Iowa, he or she must spend time meeting their fellow citizens and answering their tough questions. To that end, 30 Democratic candidates cumulatively held more than 2,400 events in Iowa since December 2016.

After technical glitches delayed the release of results this year, it hurt to read the scathing comments in the media. The New York Post’s cover page read “DUH MOINES,” while an opinion column in the Washington Post wanted to “kill” the caucuses and another in Vox called them a “terrible, anti-democratic disaster.”

Yet for all these shortcomings, there’s something special about the caucuses that is nearly impossible to explain. You have to experience it to understand. That’s why many people from outside Iowa can’t understand why caucuses survive.

I’ve wanted to caucus ever since I was 8, after I sat atop my dad’s shoulders and watched my mom, a non-native Iowan, support her candidate in 2008. She, along with friends and neighbors from our precinct, crowded into the cafeteria at what would later become my high school.

As a former reporter and editor for the Des Moines Register, my mom said it was strange to put her political beliefs on public display. She was especially alarmed when my aunt in Colorado said she’d spotted her on C-SPAN's broadcast.

In the auditorium, a separate precinct erupted into shouts and cheers as one lady wearing a green pantsuit crossed from one candidate preference group to another.

As we watched from the hallway, my dad explained how every person matters in a caucus. The lady in green might have made her new candidate “viable”—or eligible to earn delegates to the district convention.

Four years later, my mom and I braved the cold to watch Barack Obama deliver his final campaign speech in 2012. When he thanked Iowa for believing in him from the start, I felt a rush of pride: my state had established Obama as a true contender and ultimately helped him gain the traction he needed to win the presidency that year.

In 2016, even though I wasn’t old enough to participate, I still checked people in at my precinct’s caucus. My middle school gym transformed into a vicious battleground. I even watched my mild-mannered neighbor lash out at our caucus leader and demand a recount. Other people simply walked out in contempt. It was a hot, sweaty mess.

During winter break last year, my mom and I saw a variety of candidates in person—a special perk of living in Iowa—and last summer I was lucky enough to organize for a presidential campaign with a field office in my neighborhood.

Still, as I played the ground game and courted potential caucus-goers, it struck me that there was no way to participate absentee. Caucuses require boots on the ground, so I knew I’d have to go home. I booked my flight home eight months in advance, along with every political correspondent in the country.

The buildup to the caucuses is almost more impressive than the event itself. You can’t walk into a popular coffee shop or restaurant without running into an MSNBC or NPR correspondent. With this in mind, my mom and I drove around Des Moines looking for famous out-of-towners but found only two: Meet the Press anchor Chuck Todd in the Hilton Downtown and former Secretary of State John Kerry at Centro, a popular local restaurant.

Finally, the big day arrived. The air buzzed with anticipation as my mom and I drove to our caucus location, a college basketball stadium about the size of Cameron. As we walked in, we chatted with neighbors until the time came to split into candidate groups. Even my mom and I separated.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Counters took the initial headcount to establish viability and calculated 849 people in the room. To be viable, then, a candidate needed to surpass the 15% threshold with support from at least 127 people. Yet, to my surprise, the animosity that defined my caucus experience four years earlier was nowhere to be found.

The entire process went so smoothly that my mom and I agreed it was eerily orderly. Yet now is when critics decide it’s finally the moment to end my state’s democratic ritual.

But here’s my response: The caucuses are about more than just the results. They are about the retail politics that come before as candidates campaign face-to-face with their constituents. Iowa is the place where candidates are allowed to breathe and show their human side, whether that be by flipping pork chops or blocking someone's ranch dressing.

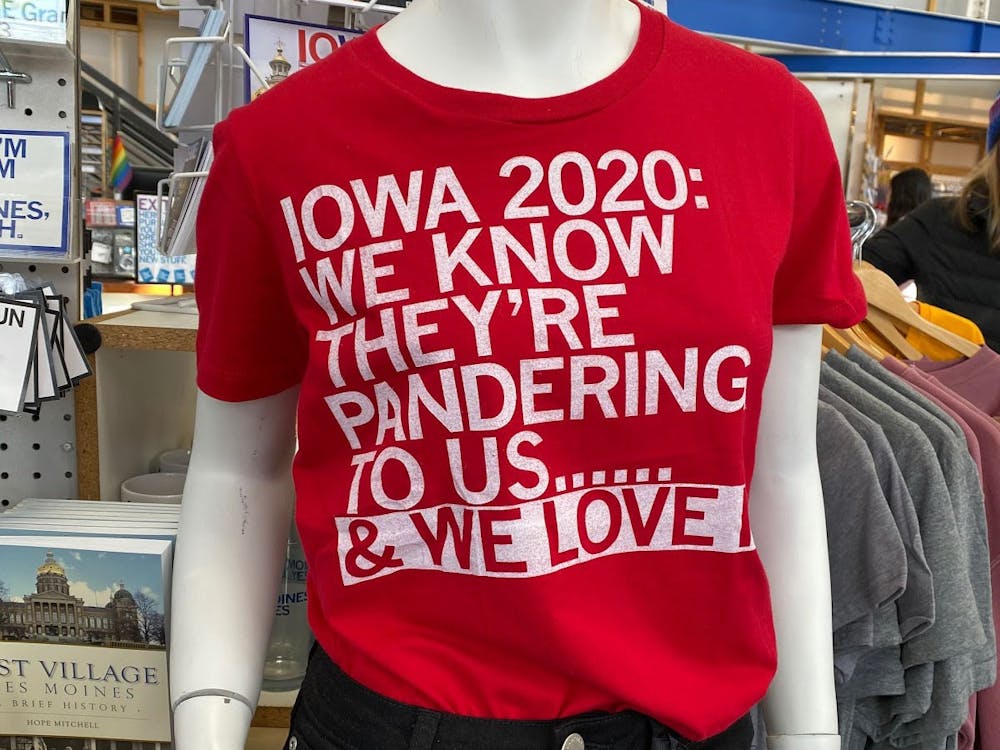

Iowans expect to interact with politicians who seek their support. We show up to campaign events, read each candidate’s policy plans and ask the candidates tough questions because of the environment that caucuses foster.

Promoting efficiency at the expense of a more human element is simply not worth the cost. Cutting out Iowa would mean transitioning from meet-your-candidate events to big multi-million-dollar ad slots. Talk about an undemocratic process.

This is a make-or-break point for Iowa’s caucuses. We worked hard to make the 2020 caucuses more accessible and efficient—and succeeded. Yes, we have some wrinkles to iron out. But we’re getting there.

Give us another chance. We’ll build an even better caucus for the future.

Maya Miller is a staff reporter in the news department.