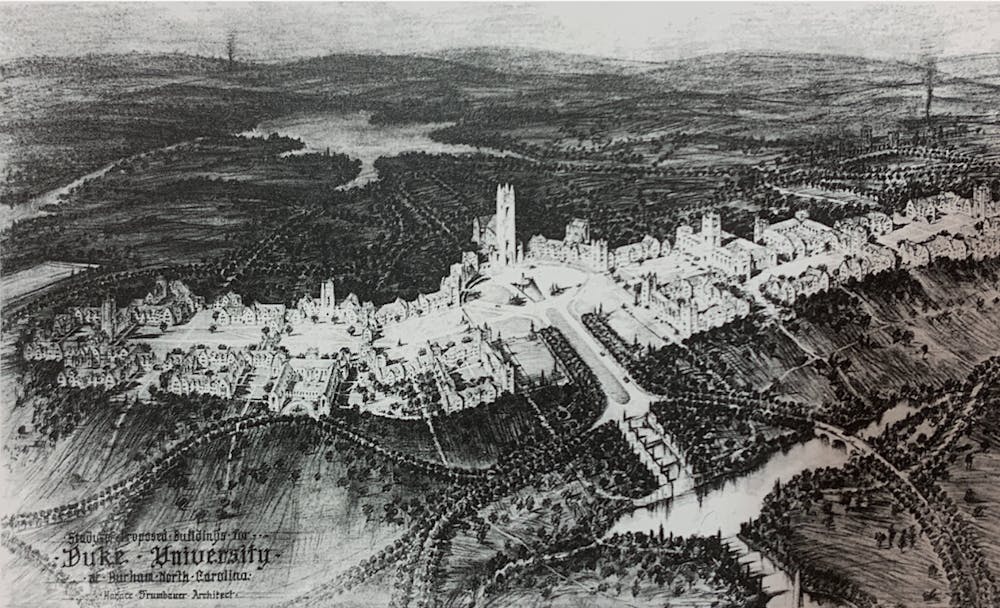

Take a close look at the picture above. A serene lake in the lower right side balances the extended fingers of the one in the upper left, bookending the dominating Duke Chapel tower between them. The Chapel itself seems to stare intensely at the bird through whose eyes we are looking, spreading its stone wings of academic and residential cottages in direct challenge to the feathers of our avian proxy.

While some of this plan materialized into today’s West Campus, a closer look at this early sketch reveals some fascinating differences. The plots of land where Few Quad and the Allen Building are located today are instead grassy fields in the picture (they remained forested fields until 1939 and 1954, respectively). Their absence triples the width of the central axis of the campus plan, and both structures flanking the Chapel correspond to this much wider center, approaching the chapel in rounded elliptical curves rather than ruler-straight parallels.

The left arm of the campus seems to extend three times as far as it does today, past where the football stadium is located. Close your eyes and imagine Duke having seven more residential quads past the existing four, all at the same elevation and in a directed promenade rather than cast off the high ridge of the main campus and clustered behind it, like Keohane, Edens, and Hollows are today.

The right arm provides every spatial counterweight to the left, reaching almost all the way to Erwin Road before stopping. Imagine if every class you have in Gross, the LSRC, Physics, Biosci, Engineering, and French required you instead to walk just a little farther than SocPsych, with none of the steep descent it takes to get to the front doors of French.

While it looks like the statue of JB Duke still stands in front of the Chapel, it also looks like there is a reflection pool surrounding him, in an even field where, in a marked difference from today’s campus, no stout oaks interrupt sightlines with trunks and branches.

This whole sketch is a remarkable text for a potential Duke University that was never fully realized. Most people’s first reaction when I show them this image in The Campus Guide is shock and interest, and usually a bit of reflective silence when they are thinking about how different everything would have been if that were what West Campus looked like today.

Much of the time, Duke’s campus gives the appearance that it is a perfect, accomplished vision of what Huxley called “the most successful essay in neo-Gothic that I know.” The main campus seems to boast under a veil of unchanging and inevitable appearance, existing as the only actual outcome of all the potentials that preceded it. I’d like for everyone to see underneath that veil for a moment by exposing the ways in which the architectural expression of the university has been contingent upon historic precedent, contextual friction, and private whim rather than total, transcendent intention and unobstructed accomplishment. You may have sensed this unveiled contingency when you closely examined the image above, but my hope is that if you have not already, some other examples will make the sensation stronger.

East and West. An academic dumbbell, shaped so to separate students by gender when coeducation was still commonly an absurdity. Inconvenient when you live on one campus and have a class on the other, right? So why are they that way? While there were always going to be two campuses (like Radcliffe and Harvard or Bernard and Columbia), the first intentions of Few and J.B. Duke were to build what is now West adjacent to East, with the Chapel where Baldwin Auditorium sits today. The style of this adjacent campus was also briefly neo-classical to match the Dorian columns and Parthenon structure of the East and West Duke buildings. Could you picture a Graeco-Roman Duke, with the iconography of a dome-on-a-square rather than the Chapel spires? Professor Frank Brown’s tour of America’s other universities gave the strong impression that Gothic was the way to go, and the ambitious Durhamites who inflated the price of land next to East provoked the distant campuses. If Few had not been wandering with his sons and come across a wooded ridge a mile from East one day, Duke could have been in any number of other places. Chance, context, and happenstance determined the eventually permanent daily feature of our campuses.

Aquatic installations. You’re all doubtlessly familiar with the giant, circular central quad between Marketplace and Lilly on East. Could you imagine it filled with a raised still water pool for reflecting by when you’re regretting that 5.5 credit overload? And the patch of garden and walkway in front of the bus stop between Allen and Few on West—could you imagine sixteen giant shooting arcs of water that spread mist in the air so much it creates a perpetual rainbow? Both of these were planned and never realized, just like the reflecting pool in the much larger quad of the image at the top of this column. The budgeting of the Depression-era builders restricted many superfluous projects like these, and they will almost certainly never be realized.

The Ackland. We’re all proudly aware of the inspiring collections and dedicated curation at the Nasher Museum, not to mention its top-tier brunches. But long before its opening in 2005, Duke was going to be home to all of William Ackland’s extensive collections as host to the Ackland Museum of Art. Although he considered a number of schools initially, by his death Ackland had settled firmly on Duke with the full support of Few, who commissioned Julian Abele to design the structure which would have been just behind SocPsych where the parking lots are. 1940 came and both Ackland and Few died, creating room for Duke’s Board of Trustees to have their way and refuse the offer, likely because the Ackland Estate would continue to own the collections and not the university. But what if they hadn’t? What would Duke be like if the Nasher site were still a preserved horticultural area and there was even less parking behind the academic quad? Where would you brunch on Sunday mornings to spend your friends’ food points? (If you want to see what the Abele-designed Ackland looked like, the Building Duke Bass Connections team worked on a stunning virtual reality structure seen here).

These examples are very few among very many, but they illustrate the insistent feature of postmodern philosophy that is the recognition of the contingency of our histories, languages, and identities in their arbitrarily selective contexts. While the immaterial examples like funding and faculty acquisitions are in fact far more interesting, the material expression of contingency in the example of Duke’s campus is an effective way to visualize what that notion means.

A single image and some brief sketches of alternative Dukes exposes the fragile reality we often perceive as a secure portrait, and to our benefit. It makes us ask interesting questions of ourselves and the potential for future alternative Dukes. What could Duke have been if any contingent part of its development were different? Who are you if Duke is different? How do we who influence the institution now use the knowledge of its contingency to shape its potential futures? What are you doing to make the Dukes That Will Be? And which one will survive?

Nicholas Chrapliwy is a Trinity junior. His column runs on alternate Fridays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.