This is part two of a three-part series about the raucous history of Duke students burning benches after major basketball victories. Here are part one and part three.

In 1992, bench-fueled bonfires got out of hand and dozens of students were injured following the Blue Devils’ national championship. The hijinks prompted a reactionary motion to strictly enforce a campus bonfire ban.

After a year’s hiatus, Public Safety—what the Duke University Police Department was known as at the time—struck back by enforcing a rule that declared bonfire tending a crime. In 1994, four students were hit with citations after a victory against Purdue carried Duke to the Final Four.

“We can never have a [University bonfire] on this campus again because people don’t know how to handle it,” Chief of Public Safety Lewis Wardell told The Chronicle in 1994.

The University staffed campus with 200 officers on the night of Saturday’s semifinal game against Florida, but even those forces were unable to quell student tradition. Public Safety cited three students for bonfire tending and arrested another, yet benches still burned after the Blue Devils’ comeback win.

Students fought the law—and the students won. The lore of tradition was difficult for Public Safety to combat.

“Burning some benches on Clocktower Quad after the regional finals was expected as a barbecue on July 4th, and something that you thought about before the game,” said Paul Hudson, Trinity ‘94, who served as Duke Student Government president.

Michael Saul, Trinity ‘94 and a Chronicle reporter who covered many of the bench burnings, said it was a difficult balance to strike between allowing students to celebrate while maintaining a safe environment.

“As the administration tried to crack down on making the celebration as safe as possible, I think to some degree, that affected the mood of some celebrations,” he said. “They seemed a little less spontaneous. For some students, I think it inhibited the fun.”

A break from Final Four appearances and UNC wins for several years gave the administration time to reflect on policy. But when 1997 rolled around and Duke downed UNC, it was more of the same. Benches burned despite police actively trying to prevent the fires.

At the time, Wardell told The Chronicle that handling students was most difficult two hours after the game—what he termed as “the critical point of drunkenness.”

Fights broke out among students and officers. Two students accused a guard of assaulting them, and another officer was punched in the face after trying to stop students carrying a bench. Multiple students described DUPD’s actions as harsh, but police said they were just maintaining order.

“I felt as though the celebration could have erupted into an uncomfortable event very quickly,” Dean of Students Sue Wasiolek told The Chronicle in 1997. “That’s what frightens me the most.”

Executive Vice President Tallman Trask explained that he would sometimes question the officers’ tactics.

“In the early years, I had angry exchanges with my police chief, who I thought was being much too paramilitary about the whole thing and just told him to calm down,” Trask said. “I went looking for him and couldn’t find him until I realized they were in the ‘command post,’ and I had to explain to him that universities don’t have command posts, and that they should get out and go on the quad where they belong.”

Paul Bumbalough, who served in a number of dean-level positions in the student life and student development office during the 1990s, wrote in an email that he had “very mixed feelings” about the basketball team’s success.

“Big wins usually ensured long nights of ugly encounters with drunk students, urgent calls to treat the injured (they literally jumped atop flaming benches or risked running through the fire scantily clad), a mound of police reports to triage the following morning after only a couple hours of sleep, and days of subsequent disciplinary hearings,” he wrote.

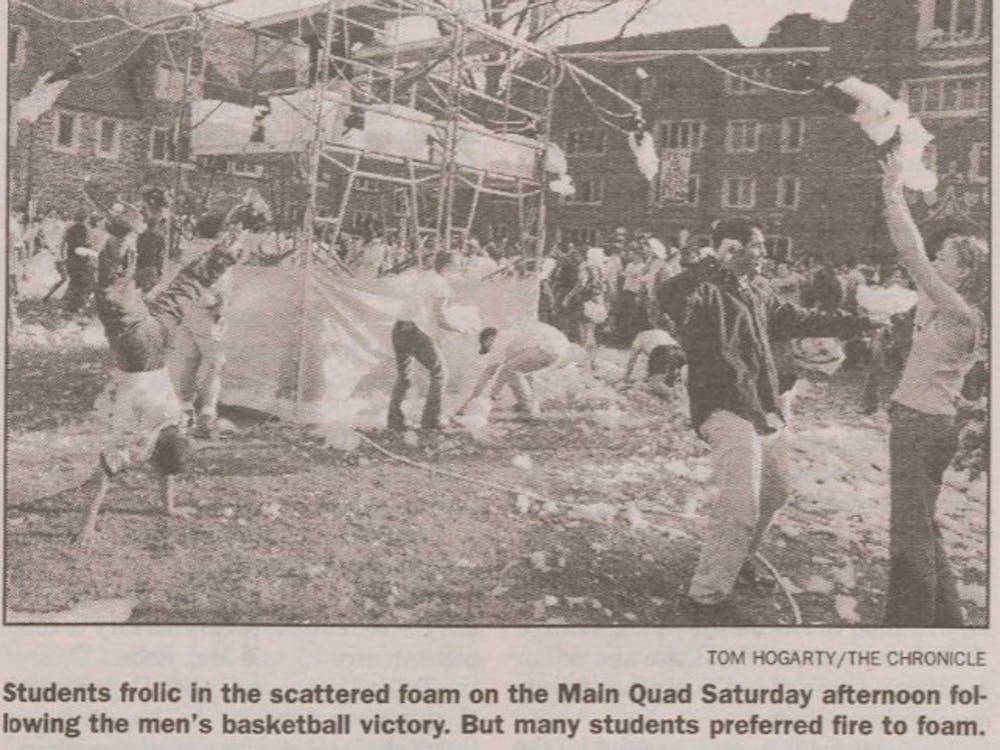

In 1998, the Campus Social Board tried to organize a foam party to celebrate a victory over UNC following the conclusion of the afternoon game. However, that effort was roundly criticized for being lame and ineffective, as the party featured little foam and ended at 8 p.m.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Once night fell, bonfires began to rise and so did tension between students and police. Two officers were sent to the emergency room, and 23 students were arrested, on a night where students accused the police of using unnecessary force. At the time, DUPD Maj. Robert Dean said that students might be resisting arrest, requiring DUPD to use more force.

“More than 1,000 students ran from one end of West Campus to the other and back again all night, setting benches on fire, igniting portions of Krzyzewskiville and hitting almost every quadrangle on West in the process,” The Chronicle reported. “Sigma Nu blasted ‘F*** the Police’ by Rage Against the Machine while a mass of students in front of the section closed in on approximately eight enforcement officials and yelled taunting phrases.”

As responders ran from fire to fire, students kept lighting them and tossed in whatever they could get their hands on, including a K-Ville tent and reclining chair. Wasiolek was hit by a water balloon launched by slingshot from a dorm room, and anarchy consumed the campus.

The smoke had barely cleared when Wasiolek ordered the removal of 14 benches that were determined to be unsound or tainted with flammable liquids.

“We’re not looking into having a ‘safe’ bonfire,” she said at the time. “Our goal is truly to keep students safe, and I’m not certain they fully accept and recognize that.”

But students didn’t react kindly to their benches being confiscated. On Tuesday night, two students hatched a plan to burn more benches on West Campus in retaliation. It was the only major modern-day bench burning not directly tied to a basketball game, but rather to perceived administrative encroachment.

Administrators and enforcement officials stood by the mob and watched students flout their authority, only stepping in to help the fires burn faster. Wasiolek was standing nearby as the flames climbed high on that Tuesday evening.

“This is absolutely one of the lowest points I’ve had,” she said.

A push to institutionalize

Stricter prohibition of bench burning fits into a larger picture of increased regulation of student life by the University.

When Hudson arrived at Duke, he recalled keg parties taking place up to six days out of the week. But by the time he left, that number had been pared down significantly. The University had also been shuffling housing assignments to make West Campus more diverse, and East Campus was transformed into a site for first-year housing.

Jeri Powell arrived at Duke in 1995 and also served as DSG president her senior year. Powell, Trinity ‘99, recalled “very significant” changes to the alcohol policy and student life.

“The bigger picture is around this shift of starting to come up with policies, and regulating what had become social institutions on campus that were totally unregulated,” she said. “The administration recognized that there was a responsibility for the health and safety of students.”

Around this time, the University received a note from the Durham fire marshal, Trask explained. The marshal said that setting fires around campus was a crime and that Duke would need to obtain permits for specific locations in the future.

“A bunch of us, including [Powell], sat down to say ‘What the hell are we gonna do?’” Trask recalled. “Because we don’t want to necessarily stop this, but [the fire marshal] is legally correct.”

The fire marshal was not keen on having firefighters running around campus trying to find and put out fires, so the group was tasked with determining specific locations.

A full-page letter in The Chronicle—signed by Powell and Trask—announced the policy shift. For the 1998-1999 season, Duke obtained six permits: two for the Duke-UNC games, one for the ACC championship, one for the Regional Finals and one for the National Championship game.

It restricted burning materials to benches or other items specifically designated for the flames. Clocktower Quad would no longer be the designated location for bench burning. Instead, DSG would notify the administration a week ahead of time whether the fire would take place on the Chapel Quad or area in front of House P, which is near the exit from the Bryan Center plaza.

“Last year, there was an uncomfortable and unnecessary confrontation between students and the administration over bonfires,” Trask and Powell wrote in the letter. “Given that such disputes are ultimately in no one’s interest, a group of students and administrators met during the summer to devise a plan under which bonfires would be allowed, but would be conducted as safely as possible.”

Powell said that looking back, the policy was effective and reduced the number of injuries without hampering the fun.

After the institutionalization of bonfires, conflict and injuries stopped dominating the headlines of postgame victories. A very similar version of the policy remains in effect today.

“In the early years, we staffed it big time to make sure it worked, but it sort of became regularized, and people understand how it’s supposed to work,” Trask said. “Students leave after four years, and they pass on a history. So after about three classes, everyone thought that’s where the bonfire was.”

Occasional controversies have cropped up, including when benches were burned following Duke’s famous comeback win against Maryland in 2001. Because the University did not have a permit for the bonfire, the Durham fire marshal temporarily revoked the permit for the UNC fire but reinstated it after negotiations with DSG and administrators.

“That went back to the spontaneous,” Trask recalled. “We sort of worked through it with the fire marshal and said, ‘Look, it’s kids,’ and they gave us back the permit.”

One recent incident was fresh in the minds of Duke administrators and fire officials who dealt with the bench burnings. The 1999 Aggie Bonfire—built by Texas A&M University to hype up students for the annual football game against the University of Texas at Austin—collapsed as students were building it. Logs crashed down, and the tragedy killed 12 people while injuring 27 more.

“We know there is tradition behind [bonfires at Duke]. Over the last two years, students have been very cooperative, but we don’t want another Texas A&M,” Durham Fire Investigator Edward Reid told The Chronicle at the time. “These illegal fires are crimes. We will punish anyone who builds renegade fires.”

Duke’s bonfires have largely managed to escape tragedy and controversy for the past decades, in large part thanks to a group of students and administrators known as the A-Team.

This article is part two of a three-part series exploring the history of bench burning. Read part one here and part three here.