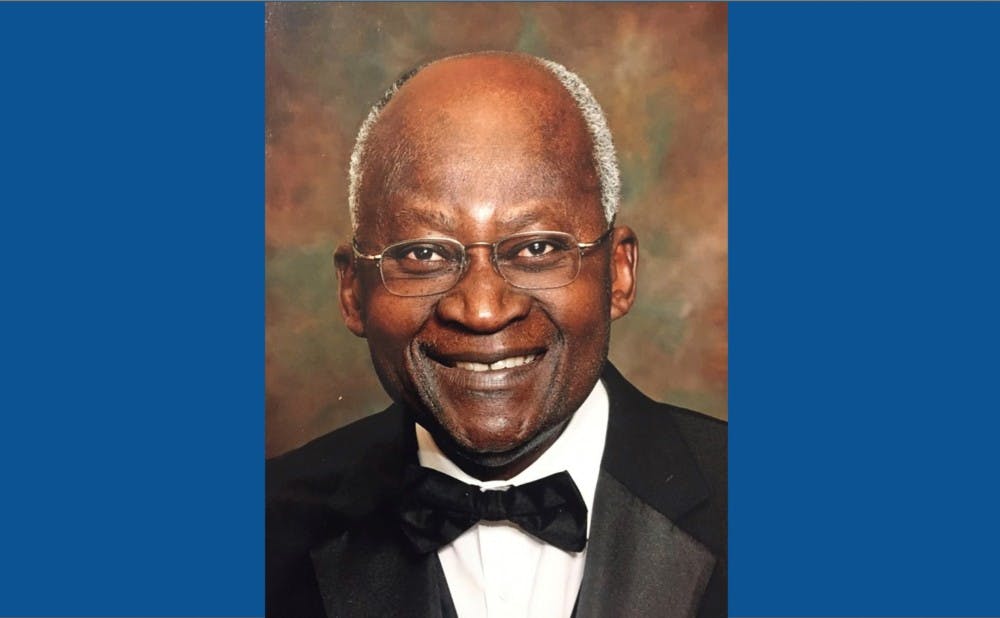

The Duke Medical Center Archives recently obtained the complete collection of writings by Onyekwere Akwari, the first African American surgeon at Duke University Medical Center.

The Akwari Papers consist of his medical findings, research papers, immigration documents, correspondences and assorted photographs. In coordination with the Department of Surgery, the DMCA spoke with his wife, Anne Akwari, who was able to package 32 boxes of material for the University.

Akwari joined the Duke faculty in 1978, following his training at the Mayo Clinic. He immigrated to the United States from his hometown in Nigeria in 1962, receiving his undergraduate and medical education in the U.S. He passed away last year at 76.

According to Lucy Waldrop, assistant director and technical services head of the DMCA, the collection “should be of note to researchers interested in studying the development of surgical medicine and diversity efforts.”

In an email, Waldrop wrote that the Akwari Papers are beneficial to those looking at the progression of African Americans and immigrants in medicine.

The School of Medicine had desegregated only a decade before Akwari’s arrival, and he was the second African American professor on an academic tenure track in its history.

Seeing what he deemed a frustrating lack of representation of African Americans in medicine, Akwari founded the Society of Black Academic Surgeons in 1989. This organization sought to expand opportunities for black surgeons while providing equal healthcare services for all Americans.

For Damon Tweedy, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, meaningful representation is fundamental to increase diversity.

“Much too often, minority success, particularly African American success, gets pigeon-holed into sports and entertainment,” Tweedy wrote in an email to The Chronicle. “The more we can normalize success in other areas, the more options young kids will see for themselves. Despite being a very good student growing up, I couldn't have imagined myself becoming a doctor or writer until I saw other African Americans succeed in that way.”

Beyond the hospital, Akwari was instrumental in creating a more welcoming Duke environment. As a member of the Athletic Council, Akwari fostered strong bonds with coaches and encouraged more student-athletes to consider medicine. He served on Academic Council, the faculty governance body. He fought tirelessly for the inclusion of women’s and minority studies for undergraduates.

Even those who didn’t know Akwari personally felt his presence.

“Although I didn't get to work with him… [his] journey is certainly inspirational and helped comfort me in recognizing that I was part of a larger journey in terms of diversifying the medical profession, ” Tweedy wrote.

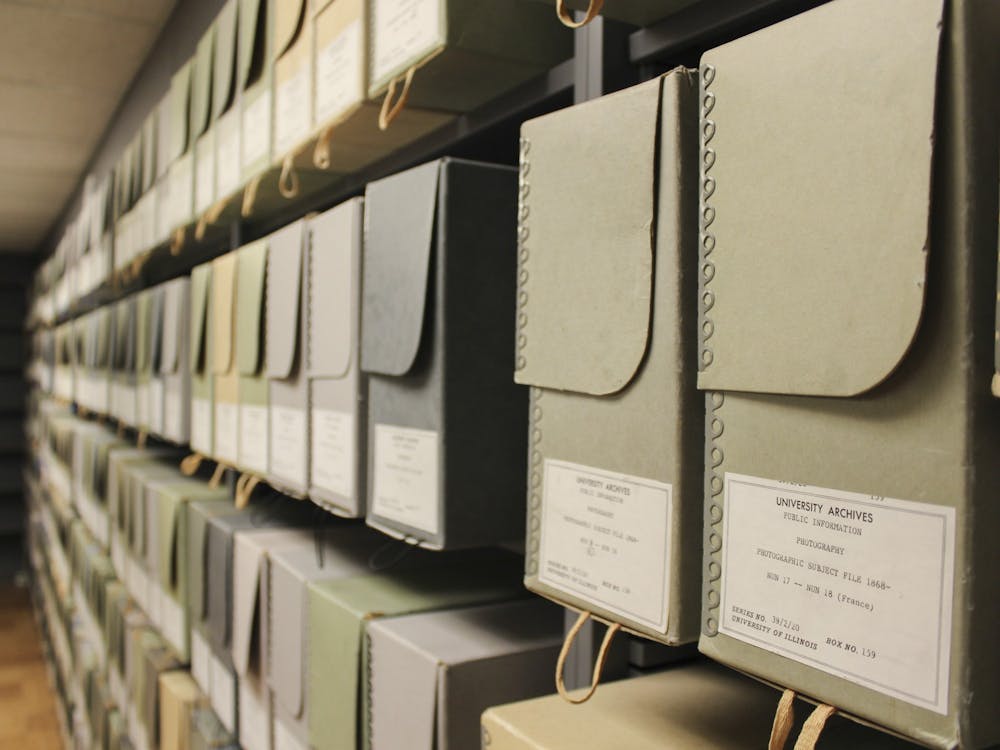

The DMCA was created in 1977 in response to a faculty-wide interest in formally collecting historical records. Before the DMCA, doctors would routinely dispose of old reports in this paper-heavy era, but thanks to a grant from the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, the Duke Medical Library began to amass old information.

Now, the DMCA houses over 10,000 linear feet of documents from the past 70 years of the hospital’s activities—long enough to walk from the Washington Duke statue on East Campus to Duke Chapel. The DMCA also collects items such as stethoscopes, blood pressure cuffs and even a doctor’s bag from the 1940s.

In addition to the Akwari Papers, the DMCA includes a number of other famous works. Two Nobel Prize winners in chemistry, Robert Lefkowitz (2012) and Paul Modrich (2015), have their papers recorded in the DMCA, as well as collections from the previous chancellors.

Correction: The story was updated Wednesday evening to reflect the correct spelling of Waldrop's name and the name of the society that Akwari founded. The Chronicle regrets the errors.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.