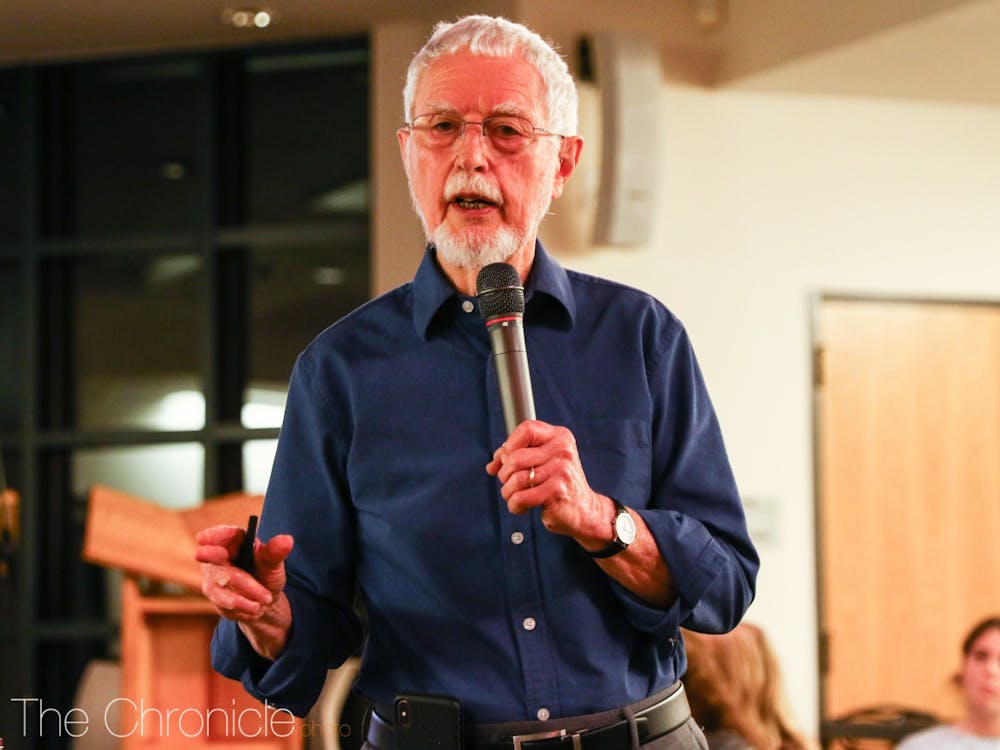

A retired professor emeritus of music at Duke told the story of his family’s flight from Nazi persecution at a Thursday event at the Freeman Center.

Alexander Silbiger, who is now a speaker at the Holocaust Speakers Bureau, spent his childhood in the Netherlands. His family fled after the German army invaded the country. Their path took them to France, Jamaica, Curacao and eventually, in Silbiger’s case, to Duke.

“What crime did we commit that we had to flee?” Silbiger asked the audience gathered to watch him speak in the Freeman Center. “Our crime was we were Jews.”

Jews were once a valued part of the Dutch community, he said, but after the German invasion, the values of the Nazi party—including hatred of Jews—spread.

Silbiger recounted memories from his childhood environment in vivid detail, including an air raid that took place on his sixth birthday, when the guests were forced to wear gas masks and hide in the basement.

“If you’ve never been in an air raid, let me tell you, it’s one of the scariest things I’ve experienced, when at any moment, some bomb may fall and explode right on you,” he said.

The Dutch army was no match for the German troops, he said, who were soon marching through the streets.

Silbiger noted that when the German occupation began, the Jews living around him seem to have underestimated what was in store. What the Jews may not have seen was that the Germans had a four-phased plan: identify, humiliate, isolate and remove.

As Silbiger described, the first phase of the plan consisted of ID cards, stamped with a large “J,” that Jewish people were forced to carry. The second and third phases featured bans from movie theaters, certain schools, restaurants and other public places.

“They were a nuisance, but not life-threatening,” Silbiger said of these restrictions.

The last rule of these phases required Jews to wear a cloth star on their chest, right above the heart.

The purpose of this, Silbiger said, was to “isolate Jews from the rest of the population—to make them appear different and a bit inferior.”

The final phase was removal. Jews were first moved to Westerbork, a transit camp in the Dutch province of Drenthe, and from there, once a week, a train would take about 1,000 people on a two-day journey to Auschwitz. There, people were separated into two categories: the fit, sent off to do essentially slave labor, and the children and elderly, sent straight to the gas chamber.

In early 1942, Silbiger’s father heard through the underground resistance building in the Netherlands that the family should leave the country—no matter how dangerous the journey.

On April 13 of that year, the family left. Using the network of the underground resistance, they began a trip south. Silbiger’s father would contact one person, who would give him another contact, and so on, until the family made it to Paris.

There, the family learned that their contact had been arrested. They stayed in Paris for six weeks, developing a cover as tourists from Belgium, until a new contact was established.

Now came what Silbiger described as the most difficult part of the whole trip: France was divided into two regions, and crossing the well-guarded border—between occupied France in the north and Vichy France—was very difficult.

“We had to run through sparsely populated areas, through fields, and crawl under barbed wire fences, and finally, cross a river,” he said.

After crossing, they were stopped by an inspector who, though he had the power to arrest them, took pity and asked the family to stay in a hotel until they could produce proper papers. This stay lasted six months, until the Dutch government provided means for the family and several other refugees to cross the Atlantic.

The idea was to go to Suriname, a Dutch overseas territory, but the governor of Suriname, afraid of spies, decided that he did not want Jewish refugees. Finally, Jamaica decided to take them in and placed the family in a refugee camp.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

“The accommodations were pretty basic, pretty sparse. But hey, we no longer had the German threat of being exterminated,” Silbiger said. He added that he spent the days playing with the other kids at the camp.

Silbiger’s father was offered a job, and the family went to the Dutch Carribean island of Curaçao. Two years later, the Germans capitulated and the family returned to Holland, imagining that everything would resume as normal.

“But the Holland we returned to was not the Holland we left,” he said.

The family’s house was an empty shell, Silbiger said. Many of their relatives, including his grandparents, had been taken to Auschwitz only a few months after the family had escaped.

Finding it difficult to adjust to life without those close to them, Silbiger’s parents decided to return to Curaçao. Silbiger went to college in the United States, at the University of Chicago, and eventually became a professor of music at Duke.

“I gradually began to realize what would’ve happened if we hadn’t left,” he said. “I thank my life to the heroic acts of my parents.”

Preetha Ramachandran is a Trinity senior and diversity, equity and inclusion coordinator for The Chronicle's 118th volume. She was previously senior editor for Volume 117.