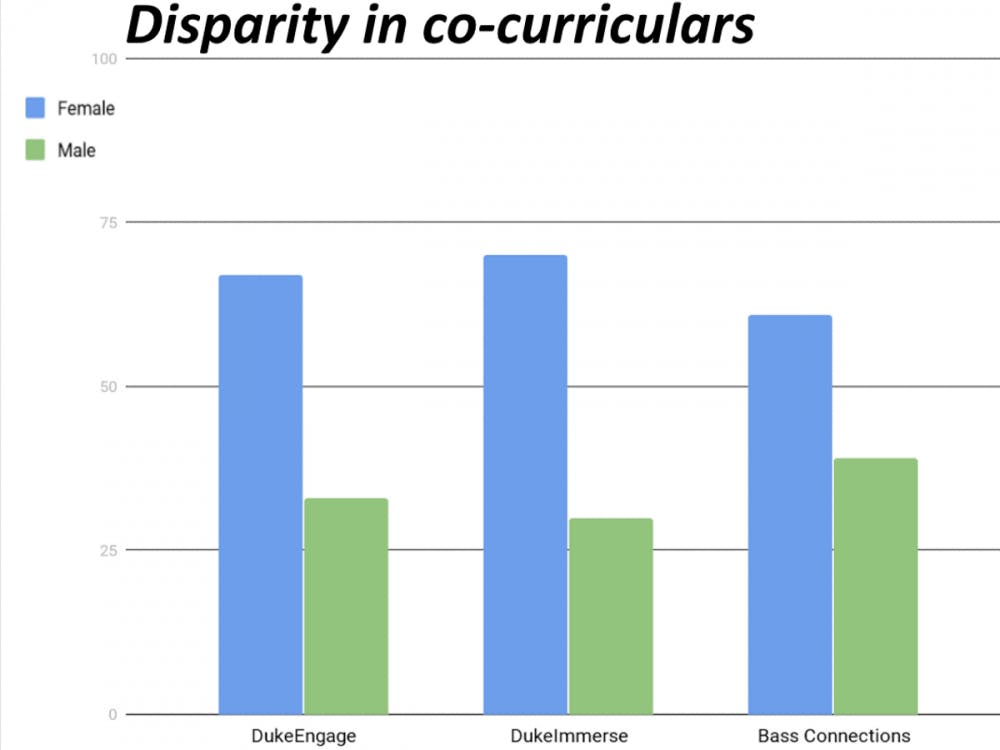

Across many different co-curricular activities at Duke, there is a disparity between female-identifying and male-identifying student participation.

Alec Greenwald, director of academic engagement for global and civic opportunities, has been leading a working group of staff and faculty across campus who are involved in student engagement. The team emerged from an annual engagement retreat and has been meeting every month for the past year and a half, he said, focusing on gathering data and addressing what might be contributing to the numerical differences.

“We recognize that the ratios we are seeing here on our campus are not dissimilar from other campuses across the country,” Greenwald said. “Right now, we’re collecting data to confirm what our instincts are around these numbers.”

Last year, DukeEngage was composed of 67% females and 33% males. Biological Sciences Undergraduate Research Fellowship, Story+ and DukeImmerse similarly demonstrated a roughly 70%-30% female-to-male ratio.

Bass Connections director Laura Howes also provided data on her program, which is currently in its seventh year.

“Across those seven years, we have seen about 61% female participants with the rest being male,” Howes said. “We also look at our stats for the application ratio. We look at the selection ratios, and our teams are representative of this.”

It is not a matter of males being disproportionately rejected from the program, Howes added, but they simply are not applying as much in the first place.

During the 2018-19 application cycle for Bass Connections, 30.0% of applications were from males, which reflected itself in 30.2% of accepted project team members. In the following year’s application cycle, 31.4% of applications were from males, making up 31.2% of the team members.

However, a discrepancy was found among the different Bass Connections themes, which involve research that intersects multiple disciplines. The highest male-to-female application ratio was for the Information, Society and Culture and the Energy & Environment themes.

The ratio between male and females is roughly equal at Duke—females make up 52% of the overall student population.

Although no concrete evidence is available to justify the numerical inequity, Greenwald mentioned many explanations have been proposed.

One claim has been that male-identifying students are more pre-professional and may be less interested in having experiences that don’t directly contribute to their pre-professional success, he said.

“This [explanation] feels sexist and gendered to me by saying female-identifying students are not pre-professional and aren’t concerned about how their experiences contribute to their pre-professional success,” Greenwald said. “My total personal opinion is that this is not something that starts at Duke. This is something that has a lot to do with how we are socialized as boys and girls growing up and what is expected of us.”

Both Howes and Greenwald expressed their concerns about the data.

“Stepping outside of the confines of Duke University to engage, however that is—study abroad, DukeEngage, civic engagement, service-learning, clubs and organizations—develops a broader kind of worldview,” Greenwald said.

Howes related her concern to the well-being of the student population as a whole.

“If a segment of the student body is opting out of co-curricular programs, they are not taking full advantage of what Duke has to offer,” she said. “This also reduces the diversity of perspectives in these programs which negatively impacts the rest of the student body as well.”

To tackle the issue head-on, Greenwald’s team has concentrated a lot of its attention on having conversations with student groups. For example, a Women’s Center initiative called the Duke Men’s Project has worked to dismantle toxic masculinity and engage men with feminist work on Duke’s campus.

The program inspires “vulnerability and authenticity” in its participants, junior Brian Glucksman, a member of the Duke’s Men’s Project leadership team, wrote in an email to The Chronicle.

He added that many of those involved initially join because they have “specific women in mind—usually friends, sometimes mothers, weirdly, almost never romantic partners—who they wish to treat more fairly or who they wish to build deeper relationships with.”

“Sometimes, as was the case with me when I enrolled my freshman year, they just want to be good men and assume (rightly, I may add) that good men should aspire to be feminists.” Glucksman wrote.

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to Hayes instead of Howes for her comment on male students not applying to Bass Connections programs as frequently as women. The Chronicle regrets the error.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.