Editor's Note: This story is part two of a four-part oral history of the 1969 Allen Building Takeover. Read part one here.

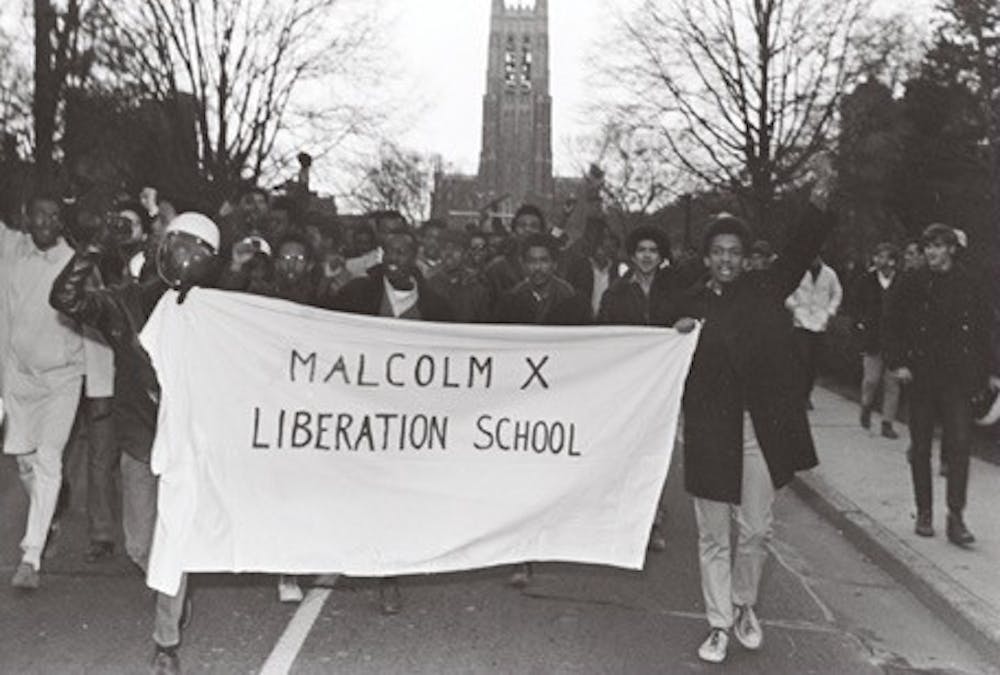

On February 13, 1969, approximately 60 Duke students occupied the first floor of the Allen Building to protest the University’s failure to meet the needs of black students. Their demands included the creation of a Department of “Afro-American” Studies, increased enrollment and financial support for black students and a black student union. Protesters remained in the building until after 5:00 p.m, when their exit ignited a clash on the main quad in front of Perkins Library between students gathered outside and police.

No two protesters experienced that day—or the months and years that followed—the same way. Over time, the protest has been absorbed into Duke’s history—there was an official commemoration on the 50th anniversary. Beyond public recognition, however, the memories and lessons of that day remain deeply personal for many of the protesters, whose lives were changed by the act of resistance, the risk of violent force and potential retaliation from the university.

From original interviews, testimony at panel events and archival material, we have compiled personal stories of the 1969 Allen Building Takeover—in the words of those who were there. Some statements have been edited for length and clarity.

'Too young to be afraid': The night before

On the evening of Feb. 12, students who decided to enter the Allen Building met to discuss the plans for the following day. Charles C. Becton, Law School ‘69—the sole graduate student to participate in the protest—hosted the meeting at his house off campus. They discussed the roles and responsibilities of each student, set expectations for how long they might be in the building and laid out specific ground rules: no students would talk to the press, no students would touch or harm any Duke employees, no students would bring weapons into the building.

Michael McBride (Trinity ‘71): The final plans were laid—that we would arrive early in the morning, that we would exit at the back of the truck, that we would clear the building.

Chuck Hopkins (Trinity ‘69): I called Mark Pinsky at The Chronicle to make sure the national press would cover it... We were smart enough to know back then that we didn’t want it to be an isolated event down here in Durham, we wanted the nation, the world to know what was going on. To their credit, not surprisingly, The Chronicle did an excellent job.

Mark Pinsky (Trinity ‘70, writer for The Chronicle): I was in the third floor of the Flowers Building... I like to refer to those years as The Chronicle's "Red Years." So we were journalists, but we were also advocates as well. We understood the contradictions, but we accepted the contradictions. So we had a very strong editorial position in support of the African American issues.

McBride: We discussed whether we would take weapons into the building... We just didn’t think that was wise. We were black folks living in the South. I thought that could only end in disaster... We actually thought there was a real possibility we might be killed anyway. Some people said we were brave, but that’s not a good word. We were not brave. We were young, and so naïve... We were too young to be afraid, I’ll put it that way.

Janice Williams (Trinity ‘72): I was a freshman in 1969. You can imagine my eyes were wide open. I was like a deer in headlights. But I was determined to follow them because I too grew up in a family where we were taught the discrimination, the hardships that blacks had suffered. My grandmother told a story to us growing up that her grandmother had actually been a slave and because she would not cry when she was whipped, the slave master cut her thumb off. So what she did was she slung her thumb and the blood and walked off and still did not cry. It was, “Don’t talk back or ask any questions,” because the moral you got was, “You gon’ be beat, you gon’ be strong, and you’re not going to cry.” So I came here with that kind of mentality and had no idea what I was walking into.

'Ready to fight the man': Inside the Allen Building

At 8:00 am, the students approached the Allen Building from Flowers Drive in a U-Haul truck. They entered the building, asked the staff to leave and chained the doors closed. Throughout the day, they played cards, did homework, listened to the news and answered phones. White students held “sympathy schools” in the upper floors of the Allen Building to discuss how to support the students below, and as the day went on a crowd gathered around the building to protect and support the students inside.

McBride: It was dark in the truck, and then there was light, and I ran out into the building.

Williams: I had to carry a piece of chain that had been cut a certain length that was to be used to barricade the double doors we were gonna go through.

Hopkins: I got on the phone, called Dean [Bill] Griffith, [dean of student affairs] and said, “Dean Griffith, this is Chuck Hopkins, chairman of the Afro-American society. We’ve just taken over the administration building. We’re in here now. And these are our demands.” I read him the eleven demands. Bill Griffith, he sort of stuttered a little bit and he finally said, “Okay Chuck, I’ll get back to you.” That was that.

Michael LeBlanc (Trinity ‘71): The school gave us three ultimatums.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Hopkins: The first time administrators came to our window and they read a statement of all the things they’ve already done for us and demanded that we leave the building.

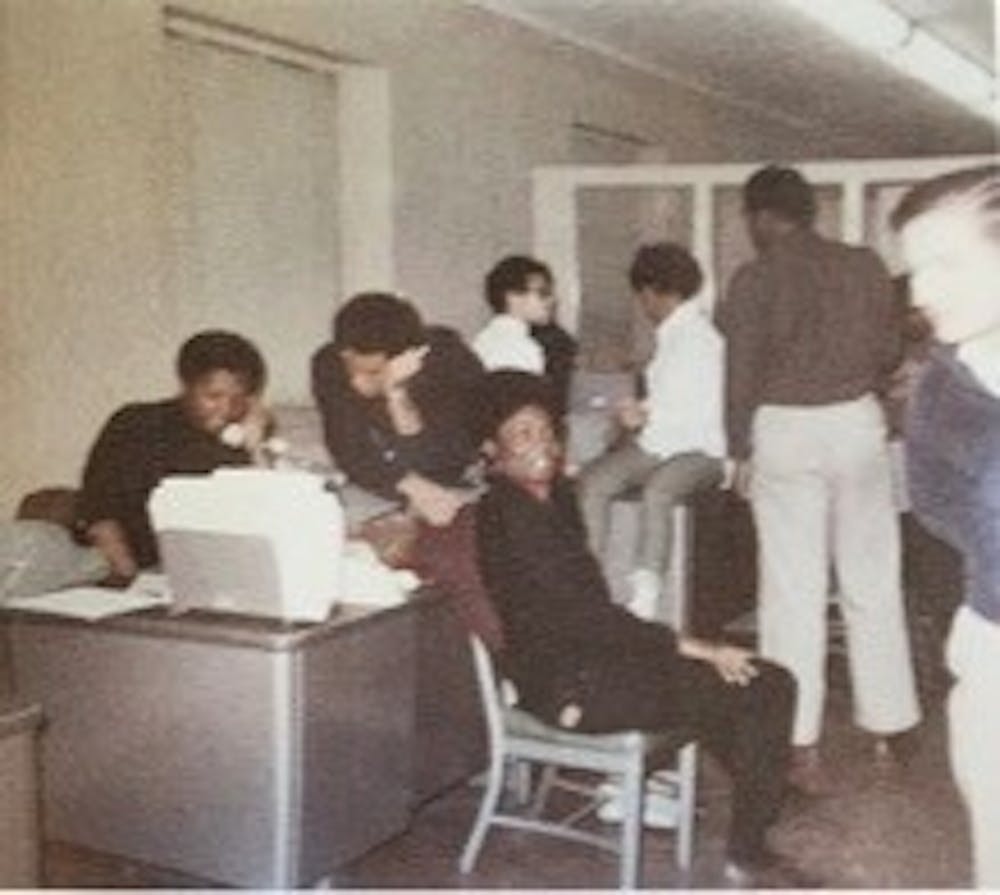

Williams: We all took shifts answering the phones... the phones were very busy. All kinds of people were calling. So friends were calling; other schools were calling; the news-people were calling; The Chronicle was calling, you know? So there was a lot of phone calls that had to be answered, and people would get tired, so then it would be your turn. They’d say, "Oh, I'm sick of these people." You know, and of course people were calling with ugly stuff. Then you really got sick of those pretty quick because you didn't want to be ugly back, and at the point where you would find yourself being ugly back, somebody would say "Okay, your turn is gonna stop."

Hopkins: The second time they were asking us to send representatives to another room in Allen Building and negotiate some things. And we were kind of making progress on that, because they were at least talking about the issues we had and our demands. At one point, it looked like something was going to come out of that, but then President Knight returned—he was away that day. He returned to campus and President Knight’s position was, ‘as long as they’re in the building, they’re not negotiating.’

McBride: I remember Tony [Axam] saying, "Mike, you gotta dissolve the officers [of the Afro-American Society]. We can't have any officers because the university will target the leaders.”

Michael LeBlanc: At the first ultimatum, a number of students decided to leave—this was maybe around 1 p.m. When you got to the 3 p.m. time frame, there was another group that decided to go. And then there was a group that just said, “we are not leaving.” Then, we got word from, I think, The Chronicle, the athletes that were on the walkie-talkies saying, “[the police] are amassing in Duke Gardens and it’s a whole bunch o’ them and they comin’.”

Catherine LeBlanc (Trinity ‘71): We prepared for the incoming of the police, and we started to put butts of cigarettes in our noses, and we had been told that if we squeeze lemon juice [around] our eyes it would help to deal with the tear gas.

Michael LeBlanc: I remember, back then, people used to smoke a lot, so they had these trash cans, black trash cans with the silver top. So we took the silver top off and put it on... So if you ever looked at it, we had filters coming out our noses, lemon in our eyes, crying, and a silver ash tray on top, and we were ready to fight the man, you know, and thinking that that’s gonna work.

Leaving the Allen Building

President Knight called the police to force the students out of the building. He was later quoted in The Chronicle, stating, “Naturally the police have been called. You knew that.” When asked about whether the Board of Trustees would have removed him had he failed to call the police, he responded, “Yes, I would have been removed, but no one ever discussed it.”

Once the protestors received word that the police were assembling in the Duke Gardens, a number of students decided to leave the building. As the doors were now locked both from the inside by the protestors and from the outside by administration, students exited through a window facing Flowers Drive with the help of students on the ground. Twenty-five students remained in the building, despite the ever-growing threat of violence, until around 5:15 p.m.

Catherine LeBlanc: The ultimatum comes that they will send police to get us if we don’t leave.

Williams: Howard Fuller, [a community activist in Durham,] came in and actually saved our lives, because he and Ben Ruffin [another activist] and a couple—we had a couple of people from Black Panthers who came to us—they really said, “Look, it’s no way, these walls—nobody can see through them, the guard’s going to come in here; they’ve got weapons; you all are going to be dead. You are going to be a bunch of dead people. Because their adrenaline is pumping and they’re armed for combat. They’re going to come in here to fight. They don’t care what you do. It’s going to be your word against theirs as to what happened inside this building.”

Charles Becton: We take a vote on whether or not we’re going to stay or leave. The first vote, I believe, is 13 to 12 to stay in the building... Someone asked for a recount. When they recounted, it was still 13 to stay, 12 to go, but I announced it as 13 to go and 12 to stay.

Michael LeBlanc: I am so glad he lied.

Williams: The guys, being very proud, very much using double standard in a sense, said the only way they were coming out was if they came out a door—I climbed out the window.

When I left out of the building, I was scared to death that I was really going to see what I had only been reading about or seeing in the aftermath of Alabama. I didn't come to school for that... And I really just believe it was fate that I ran into the security guard that I saw the most whenever I was coming back on East Campus past curfew. I think he used his guts and his instincts to say, "Let me trust this young lady and open this door." I was so happy that they came out before the National Guard came, you know, just so relieved.

Read part three here.