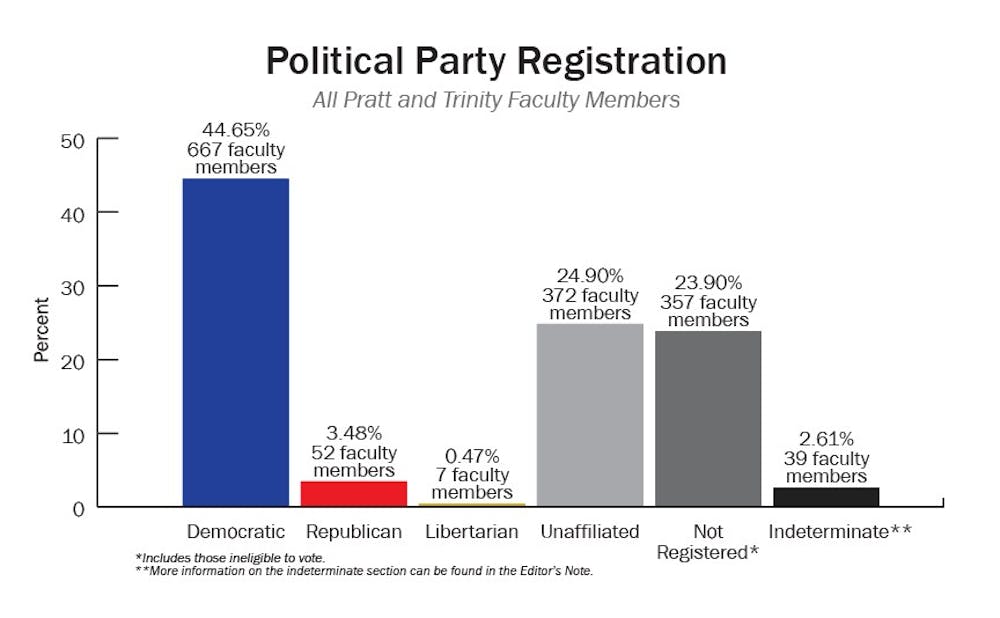

Nearly half of all faculty members in the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences and the Pratt School of Engineering are registered under the Democratic Party in North Carolina. But not even 4% of the faculty members are registered under the Republican and Libertarian Parties.

The Chronicle attempted to collect the political party registration of all Trinity and Pratt faculty members using online North Carolina voter registration records. According to The Chronicle’s analysis, 44.65% of faculty members are registered Democrats, 24.90% are unaffiliated, 23.90% are not registered—including those who are ineligible to register, such as faculty who are not naturalized in the United States—3.48% are registered Republicans and 0.47% are registered Libertarians. There were 2.61% of faculty members whose voter records were indeterminate.

Other schools at Duke, such as the Sanford School of Public Policy or the Nicholas School of the Environment, were not included in the analysis. More information on the data set can be found here in our Editor’s Note.

Seth Masket, professor of the political science department at the University of Denver, explained that these statistics are similar to those at other universities.

“This is consistent with what people have found across the U.S.—that academia tends to be heavily dominated by more liberal faculty members, that Republicans and conservatives are not very well represented at universities among faculty members,” he said.

Masket said this disparity could be attributable to many factors, and that it would be difficult “to hone in any single reason.”

Still he explained that, overall, “Democrats and liberals are more drawn to the academic life” and Republicans “tend more toward professions [other] than academia.” He postulated that these two effects reinforce each other, as conservatives may see the prevalence of Democrats at universities and become averse to working in such a climate.

“The Republican Party itself for many years now has made a point of criticizing academia as to one of its go-to talking points, saying that academics do not understand what is really wrong with the country—that they have all of their intellectual Ivy League pursuits but do not understand what faces real Americans,” Masket said.

However, Masket explained that, to a large extent, faculty members’ political party affiliation does not affect their teaching. He outlined that departments such as history, sociology or political science are the “most sensitive areas” for such a consideration, as they engage more with political issues.

Nevertheless, he has noticed as a political scientist that there are “real norms” for faculty not to appear biased toward any political party.

“There is a lot of criticism of academia about being biased, and academics are pretty sensitive to those concerns and really try not to teach that,” Masket said. “It is generally considered a poor form of teaching for [faculty members] to just tell what they believe and why students should follow that.”

Valerie Ashby, dean of the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, wrote in a statement to The Chronicle that she “[respects] the privacy of [the faculty’s] choices made at the polls” and that “political party identification plays no part in how we recruit or retain Duke faculty.”

Ravi Bellamkonda, dean of the Pratt School of Engineering and professor of biomedical engineering, similarly said that a faculty member’s political party is “private.”

Although he acknowledged that engineering faculty tends to be more conservative nationally than arts and sciences faculty, Bellamkonda emphasized that engineers are “wired to look at the facts of the case and do an analysis.”

“Engineers are trained, in any given situation, to not bring bias to the table because that affects things,” Bellamkonda said. “The whole point is to analyze the issue and come to some conclusions based on analysis and modeling. Maybe some of that is playing in where their preference is to be unaffiliated, and—depending on the issue or the candidate—then they’ll choose.”

Michael Munger, professor of political science, explained that he was formerly on faculty at Dartmouth College, University of Texas at Austin and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, but none of those schools were quite like Duke.

“The reason I have been at Duke nearly 25 years is that Duke is by far the most intellectually open place that I have ever been,” Munger said. “I really do think there is more support here for looking at both or all sides of a question than there are in a lot of places.”

Provost Sally Kornbluth did not respond to multiple requests from The Chronicle to comment on this article.

A voter’s party registration: An ‘identity’ or a ‘summary of preferences’?

Christopher Johnston, associate professor of political science, described the two major perspectives in political science on what it means for someone to register under a political party.

The first viewpoint is that partisanship is a summary of a voter’s preferences, otherwise known as an ideology.

“When they say ‘I am a Republican,’ what they are telling you is that, ‘My political preferences are closer to the Republican Party than the Democratic Party,’ but partisanship itself may not be having an impact on political behavior,” Johnston said. “It’s more of a reflection of people’s preferences and values than it is itself a prime mover of behavior.”

The second perspective describes partisanship as an identity, when a political party becomes a driving factor behind someone’s life and actions.

“It is more than just a summary of my political preferences,” Johnston said. “It is a part of who I am.”

He elaborated that this view describes partisanship as having a causal impact on behavior. This perspective would also provide evidence for how a partisan identity can bias a voter’s information processing, Johnston said.

“Even if I disagree with a candidate on the issues, I might put that to the side or ignore the places I see disagreement in order to be able to support the candidate of my team,” Johnston said.

He added that the two perspectives are difficult to disentangle, as survey data shows that they tend to reinforce each other and make similar predictions of vote outcomes.

Masket provided insight to what it means when voters do not register under a political party.

“They will evaluate the evidence and claims made by different parties and make a decision at the time of the election, but they do not want to be beholden to one party or the other,” Masket said.

However, he noted that unaffiliated and affiliated voters tend to vote similarly.

“That is to say [unaffiliated voters] tend to be loyal to one party or the other,” Masket said. “They tend to stick to one party for a long period of time. Unaffiliated [voters] who are lean Democrats tend to vote as reliably Democratic as those people who call themselves as weak Democrats.”

‘Voting matters’: Registration rates vary greatly by department

There is a norm in the United States that people are encouraged to vote, Masket explained, but voter turnout is “somewhat low” compared to most democracies.

“At least in presidential elections, at least half of the population will vote. Generally, people will register just for the ability to do that,” he said. “It does not mean they are going to vote every time–to have that freedom and the ability to weigh in in that election.”

Masket explained that voters in most states, including North Carolina, must register to vote prior to an election.

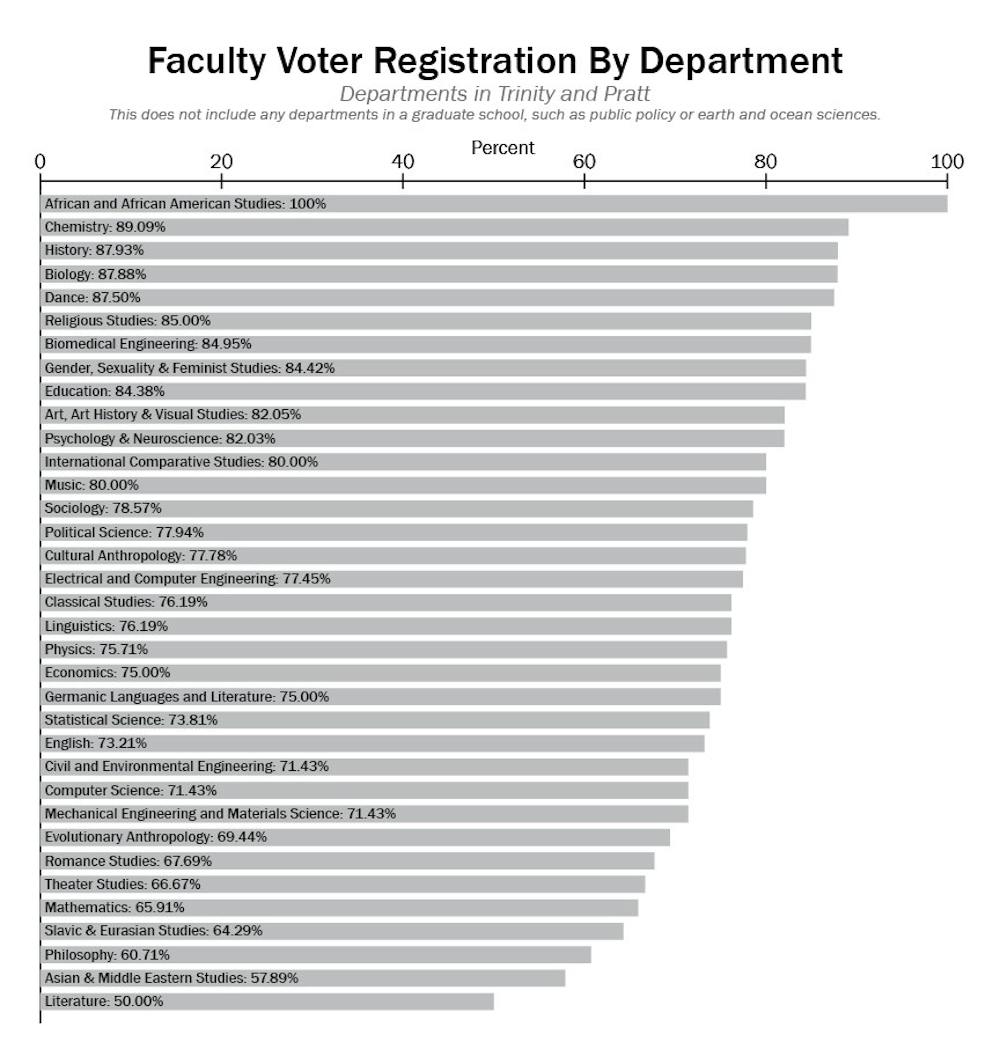

In Trinity and Pratt, voter registration by department varies—some departments have all members registered, whereas others have only half.

The departments with the highest levels of voter registration are African and African American studies—with 100% of its faculty registered to vote—chemistry at 89.09% and history at 87.93%. The literature, Asian and Middle Eastern studies and philosophy departments had the lowest voter registration percentages at 50.00%, 57.89% and 60.71%, respectively.

Mark Anthony Neal, James B. Duke professor and chair of African and African American studies, did not respond to requests to comment from The Chronicle. Rey Chow, Anne Firor Scott professor and chair of literature, declined a request to comment.

Masket said that it is uncertain whether the voter registration percentages differ because of political engagement or due to other factors, such as American citizenship and faculty rank.

“It is hard to know if we are capturing interesting distinctions about people’s engagement in politics or if this is really being driven by the percent of a department that are not U.S. citizens who are not eligible to vote,” he said. “It could also be that some of the departments with the lower percentages have a higher percentage of new faculty or temporary faculty—the adjuncts and lecturers that do not plan to be in North Carolina for very long and simply have not registered because of that.”

Adriane Lentz-Smith, associate professor of history, wrote in an email that she was dismayed that all Duke departments didn’t have high voter registration.

“Still, it does not surprise me that History would have high rates: we study politics, economy and society across the centuries and thus have a long view on how people have worked to shape state power,” she wrote.

Lentz-Smith, who has a secondary appointment in the African and African American studies department, elaborated on African and African American studies being the only department to have all faculty members registered to vote.

“As a scholar of African American history, I vote to honor the people who put their lives on the line to secure the franchise—and in defiance of those defenders of white democracy who fought and killed to keep people of color from participating in politics,” Lentz-Smith wrote. “We need only look to contemporary shenanigans aimed at cutting down voter participation to understand that voting matters.”

All four engineering departments boasted registration rates above 70%.

Biomedical engineering (BME) had the seventh-highest percentage of its faculty registered to vote at 84.95%. Electrical and computer engineering (ECE) had 77.45% of its faculty registered to vote, and 71.43% of the faculty in both the civil and environmental engineering (CEE) and mechanical engineering and materials science (MEMS) departments are registered to vote.

Bellamkonda explained that BME may have a high rate of voter registration because those who are drawn to biomedical engineering “have a desire or need to more directly see the purpose, meaning and application of their work.”

“Perhaps we can draw some inferences from that sample of the population pursuing BME and what the implications might be for a social, political act like [voter] registration,” Bellamkonda said.

Krishnendu Chakrabarty, John Cocke professor and chair of electrical and computer engineering, explained why certain faculty members in the department might not be registered.

“Members of our faculty were born outside of the U.S.,” Chakrabarty said. “In ECE, people were born in India—like me—China, Korea and other places all over the world. Many of them naturalized maybe a year or five years ago and may have not yet registered to vote.”

‘Is it a crisis?’

North Carolinians can register under one of the five recognized political parties—Constitution, Democratic, Green, Libertarian or Republican—or choose not to register under one at all. No faculty member is registered under the Constitution or Green Parties, according to The Chronicle’s analysis.

More than half of faculty members in the social sciences are registered under the Democratic Party, whereas the plurality of the faculty of the natural sciences and arts and humanities are registered Democrats.

To Munger, a registered Libertarian and the 2008 Libertarian candidate for North Carolina governor, the objective of the academy is education. In light of that purpose, he questioned whether party affiliation was relevant.

“The question is not whether there is a diversity of viewpoints on the faculty—the question is whether the faculty are capable of presenting both or all sides in the debate,” Munger said. “It might be that they are not. That is a fair argument.”

However, although some view a political party as a personal view that is not brought into the classroom, others may counter that a fair process of selecting faculty would be matching the faculty’s political affiliation to reflect that of the larger population.

“If the process of faculty selection is fair, if it is ideologically neutral, shouldn’t the proportions of the faculty have about the same number of Republicans and Libertarians as the larger population?” Munger said in explaining the hypothetical. “And if they don’t, is that a sign of bias in hiring?”

Johnston explained that a faculty member’s political party in the social sciences may shape how they ask questions and structure models for their research.

As a political psychologist, he said that if there were more conservative political psychologists, they may pose different types of research questions than a more left-leaning faculty member would.

“Because of [political identity biases information processing], I tend to worry that we may be missing out on some important discoveries in our field because we are too homogenous,” Johnston said. “We do not have enough diversity in political orientation and so we are missing out on some important questions we could be asking that just do not occur to people that are left wing.”

In addition to the types of questions, Johnston said that bias can influence how certain variables are labeled in academic research.

For example, he recently reviewed a paper on system justification, which is when an individual fulfills their underlying needs by defending the status quo, even when doing so may harm others. Johnston explained this phenomena occurs when people are “motivated to see what is good and right and legitimate because they are uncomfortable with changes in values and institutions.”

Johnston elaborated that there is a theory about system justification that a person wants to view their own group as a good group in addition to viewing oneself as a good individual.

In the paper he reviewed, the authors operationalized system justification on attitudes on climate change. Johnston provided an example of something that could be measure such attitudes—otherwise known as a scale—as “the Earth has enough resources to last us as long as we need.”

He pushed back on the authors’ assumption that system justification could be applied to views on climate change. Many others could perceive climate change as a “belief about the world,” Johnston said.

“To call that system justification or denial of reality is problematic. It seems to come from a perspective that is assuming something about the world because of political orientation,” he said. “Political orientation influencing a belief about reality that leads researchers to place a certain label on a construct that might not actually be appropriate—at the very least would be contentious.”

Johnston said that he does worry a bit about political psychology in those two respects but does not believe it to be a crisis.

“Is it a crisis? I do not think it is a crisis,” Johnston said. “I just think that, at the margin, it would probably be better to have more ideological diversity in the social sciences.”

The Chronicle emailed 10 faculty members who are registered Republicans, but only two of them replied. Both wrote in separate emails that their political views do not align with those currently held by the Republican Party and did not respond to further request for comment.

Engineers 'tend not to be a very political bunch’

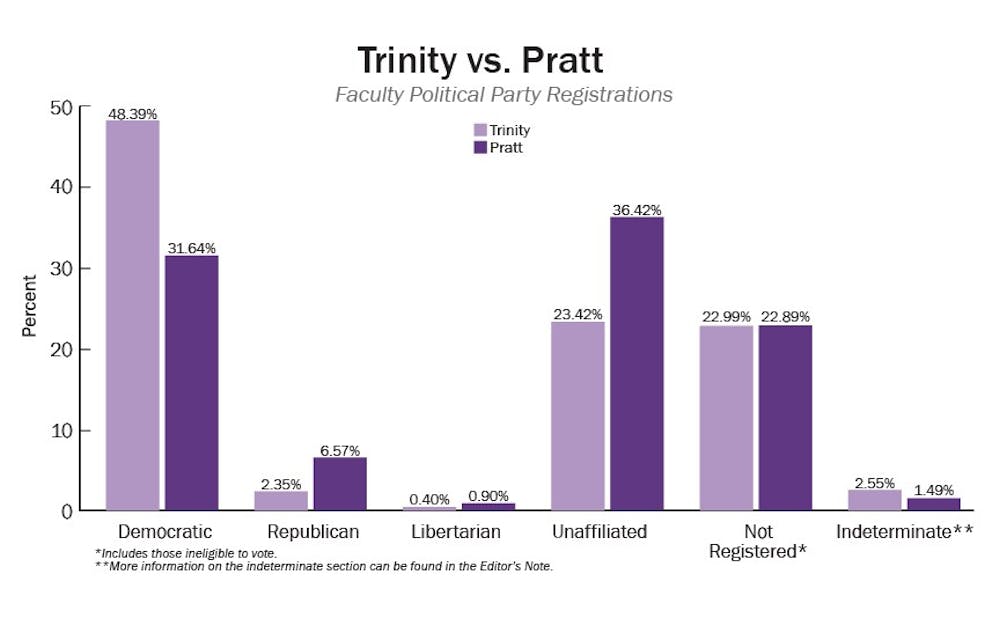

In contrast to departments in Trinity, the plurality of faculty in each engineering department are unaffiliated voters.

Of all engineering departments, BME has the highest percentage of faculty registered to vote but not registered under a political party at 43.01%. A third of CEE is unaffiliated, whereas 35.29% of ECE and 32.47% of MEMS are unaffiliated.

“In engineering, because of the nature of the pedagogy, we generally tend not to be a very political bunch,” Bellamkonda said.

Chakrabarty echoed that he would expect for Pratt as a whole to have more unaffiliated voters than Trinity.

“Engineers tend to be more skeptical,” Chakrabarty said. “They ask more questions. They aren’t going to go by what they hear. They want to find out themselves.”

When it comes to those registered under a political party, Pratt faculty members lean Democratic with 31.64% registered as Democrats and 7.46% registered as Republicans or Libertarians.

Faculty age may explain the percentage of Democratic voters in Pratt, Chakrabarty speculated.

“We have a few faculty who are in their 70s and 80s. But there are very few in 60s, and many who are in their 40s and 50s and even younger,” he said. “There is a trend nationwide that those who are younger tend to be more blue.”

Chakrabarty also said that, although he is a registered Democratic voter, he focuses more on a specific candidate than a party’s platform and believes faculty in the ECE department would do the same.

Bellamkonda and Chakrabarty both noted that political party registration does not come up as often in engineering courses as it may in some arts and sciences disciplines.

Although engineers traditionally do not view themselves as being political, Bellamkonda said, their work is approaching an inevitable intersection with politics.

“If you look at what’s happening in Facebook and other places [involving artificial intelligence], engineers no longer can say that what they do does not have implications that are political or in research allocations or information and such,” he added.

To address this, Bellamkonda said Pratt has recently standardized ethical aspects of technologies and has started a program to incorporate such content into existing classes in Pratt and the computer science department in Trinity.

Another intersection of engineering and politics is the “impact of the party in power of funding levels and research allocations,” Chakrabarty noted. He claimed that faculty in Pratt may lean toward a certain party due to basic research funding but acknowledged that he could not provide definitive proof.

“Typically if you look at funding for [National Science Foundation] or [National Institutes of Health], [projects] have been funded more when they have Democrats in power,” he said. “Whereas, if you look at the funding for the Army, the Air Force, Navy or [Department of Defense] agencies, they tend to give much more funding when they have Republicans in power.”

‘A hunger for students on the left’

As the director of the philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) certificate, Munger applies the concept that an intellectual should be able to effectively argue all sides of an argument in the program’s senior year capstone. In the course, PPE students routinely debate all perspectives of difficult questions.

In fact, students must prepare to argue all sides of the questions because they do not know which perspective they will be assigned to defend until the day of the debates. Munger noted that this is a skill that intellectuals should be expected to have.

However, not all students have such an opportunity to defend a perspective other than their own. Students on the right “learn how to argue,” but students on the left “just get patted on the head,” he said.

When he has spoken at other universities, such as Brown, Munger said students have approached him after the lectures with praise for bringing well-argued perspectives—even if the students disagreed with them.

“I think there is a hunger for students on the left to hear the best form of the arguments that they disagree with. They are smart. They are capable of coming up with their own reasons,” Munger said. “It is as if the people on the left are afraid that having students hear the best form of the argument that they disagree with, students are not smart enough to know why it is wrong.”

Munger does not believe himself to be alone in his beliefs about viewpoint diversity, as he stated that there are many Democratic professors who would echo his arguments.

He also added that there is “more support” at Duke for evaluating all perspectives of an argument than at other universities.

“The real consideration for me is not so much if your personal beliefs are on the left or right, but are you capable as an intellectual of making sure that students know the arguments and counter arguments—if nothing else to make sure that students on the left are capable of carrying out their function in an informed citizenry in a democracy,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Stefanie Pousoulides is The Chronicle's Investigations Editor. A senior from Akron, Ohio, Stefanie is double majoring in political science and international comparative studies and serves as a Senior Editor of The Muse Magazine, Duke's feminist magazine. She is also a former co-Editor-in-Chief of The Muse Magazine and a former reporting intern at PolitiFact in Washington, D.C.