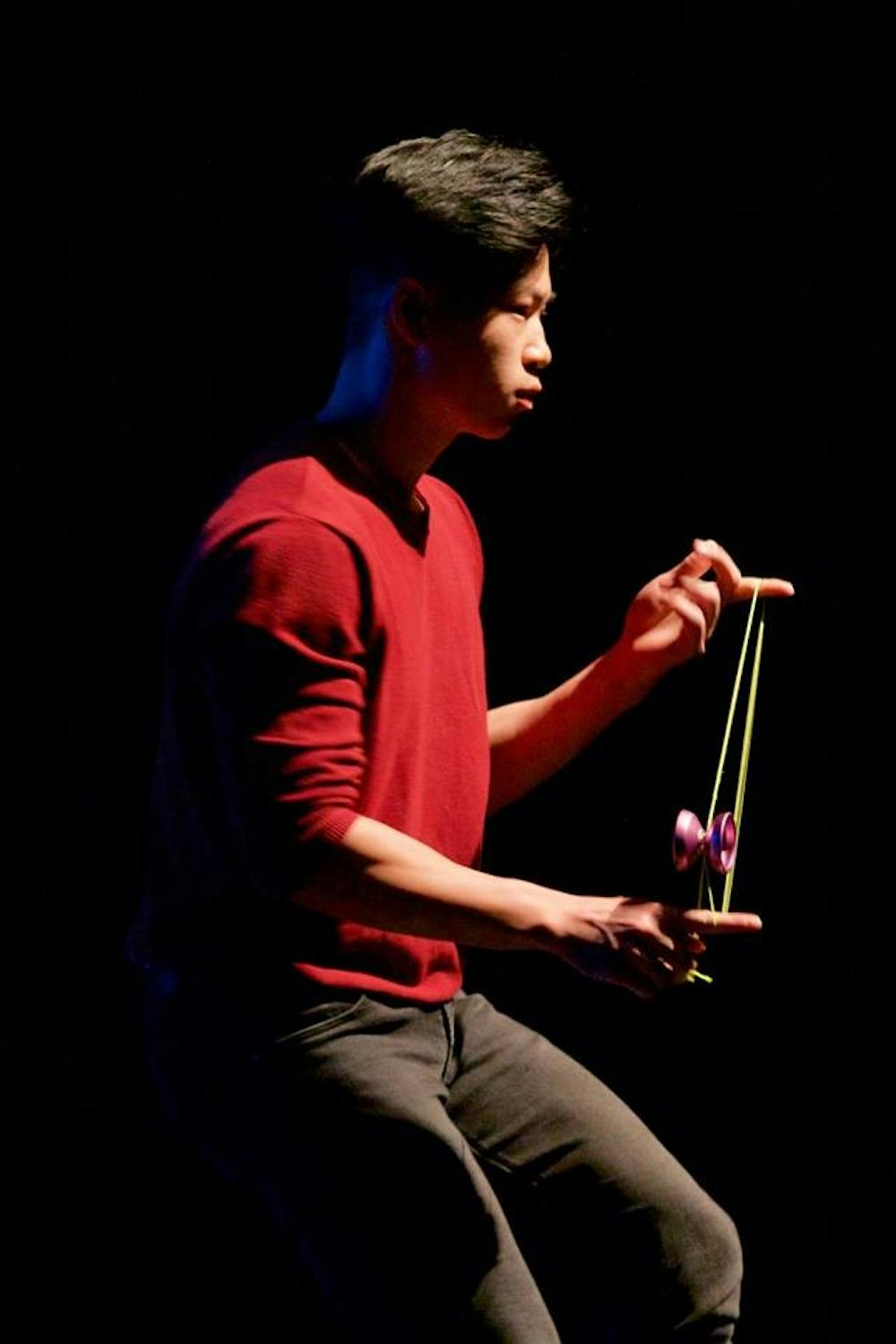

The stage opens in darkness, but the crowd is already cheering. When the lights come on, sophomore Ethan Cheung is standing on the stage ready to perform. He’s not dressed for dancing—this is far more complex. He’s not holding a musical instrument—his is far more precise.

The metallic yoyo spins through the air, moving first one way, then another with the slightest motion of his fingers. Behind his back, around his head, and between his legs, so fast you can practically hear the string thrumming. The crowd can’t get enough.

Then the music winds down. Cheung bows and runs off as the crowd goes wild. In the background, the stage lighting darkens from blue to red. When he returns, there’s something new in his hands. Two batons connected by a string, with an axle balanced like a tightrope walker between them. This is the Chinese yoyo, here to upstage its Western cousin.

The frantic pacing of Cheung’s earlier routine gives way to smooth, looping motions. The diabolo, as it’s also known, moves purposefully in his steady hands. At times, the crowd is so lost in his routine that Cheung spares a hand to wave at them. Snapping out of their reverie, they roar.

From shy kid to stage performer

In elementary school, Cheung’s uncle gave him a yoyo. At the time, America was going through a yoyoing phase and every kid in school seemed to have one. Cheung learned a few tricks to impress his classmates, but when the craze faded, he put his yoyo away and didn’t think much of it. It wasn’t until several years later that, encouraged by the same uncle, he took up yoyoing again.

“I just really enjoyed doing it and I kept going with it,” he said. “That’s sort of the philosophy I’ve taken into all things in my life.”

Cheung’s first professional competition was at the World Yoyo Contest, the international-level competition, in Orlando, Florida in 2013. He was 14 years old at the time.

“I went in with a mindset of, ‘Okay, I’ll just do some of my cool tricks and not focus too much on the points.” The result? “I placed 129th overall,” Cheung said, laughing. But the low ranking didn’t deter him. He already knew he wanted to go back.

As he grew older, Cheung competed more and more, pushing outside of his comfort zone each time. As a 14-year-old just starting out, he was shy and would often get stage fright when he performed in front of other people. When I asked him how he got over it, he shrugged.

“To compete, you have to perform,” he said. And perform he did.

He started practicing a few hours a day every week—hours spent cutting music and mixing beats, getting the choreography for his routine just right. The work paid off.

In 2017, Cheung returned to Worlds, this time hosted at the famous Harpa concert hall in Reykjavik, Iceland. This time, he placed 10th. The shy 14-year-old was gone, transformed by dedication and practice into one of the best professional yoyoers in the world.

As Cheung is performing at Lunar New Year, someone else is watching from backstage. Waiting in the wings of the theater is another young man, junior Jason Lee.

When Cheung finishes his Chinese yoyo routine, he bows and exits to stage right, bumping fists with Lee as he passes. Lee walks out onto the stage and takes out his own Chinese yoyo and begins his routine.

Where Cheung’s routine was slow and smooth, Lee immediately turns up the heat with several fast-paced loops, spins, and tosses. The applause is electrifying.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Lee walks to the front of the stage and picks up two axles as the lights fade to black. These new axles shine an eerie blue in the dark theater. As Lee begins the new routine, the axles bob and float like the lights of an anglerfish, entrancing and hypnotic. The audience is gasping now, their disbelief palpable. With the lights off, it seems like the strings have disappeared and the lights are moving by themselves, dancing in the dark.

To watch and learn

There’s a Grand Asia Market in Cary, about 20 minutes away from the town where Lee grew up. On a trip here one afternoon, Lee’s mom bought her son a Chinese yoyo kit. He was in second grade at the time.

Every weekend, Lee would attend a Saturday Chinese school. Here, people from the local community taught Mandarin lessons, helped kids learn about Chinese culture and gave the children an outlet for recreation.

One of the activities offered at Chinese school was lessons with the Chinese yoyo. Since Lee’s parents didn’t want to pay the extra fee, he often sat on the sidelines as the other kids practiced. He watched and learned and quietly improved.

As Lee grew up, he practiced tricks that he found on YouTube tutorials and performed them at middle school talent shows and international showcases. Each time he dropped the axle or failed to land a trick, it might have felt like a failure. But it wasn’t. With each new attempt, Lee was getting better and better.

Lee emphasized the importance of the performance. Like figure-skating, competitive yoyoing blurs the line between a sport and an art. Clean tricks and impressive choreography go hand-in-hand with good choice of music and interaction with the audience. A good yoyoer, in other words, is a good entertainer.

“Anyone can go up and do tricks,” he said. “But if it’s not tied together well, then it just looks sloppy.”

Seeing Lee perform, it might surprise you to know that Lee has never competed in any professional competitions. For him, yoyoing has always been a more private and personal hobby.

“I don’t think I would’ve stepped out and auditioned for Lunar New Year if I hadn’t seen other people doing it,” he told me. “I didn’t know it could be something that other people found value in.”

When his solo routine is done, Lee snatches the axle from his string and holds it up like a trophy for the crowd to see. The audience cheers, ecstatic. Cheung runs back onto the stage and snatches the axle from Lee’s hands with his string. He does a few warmup loops, then tosses the axle back to Lee and picks up another from the stage. They’re both yoyoing now.

As the music starts, Cheung drifts over to Lee’s side of the stage. They smile and bump fists. This is the duo performance the crowd has been waiting all night to see.

Their routine has everything. The fast, energetic tone of Cheung’s loops and spins is there, as well as the smooth precision of Lee’s through-the-legs movements. They toss the axles back and forth, comfortable and at ease. Their styles are unique and different, but complementary in a way that clearly enhances the performance. I won’t spoil their last trick, but the crowd goes wild when it’s over. Laughing and smiling, they exit stage right.

‘It’s fun to do together’

Junior Vinit Parekh, a local yoyo enthusiast and Fix My Campus guru, lived on Lee’s hall in Brown during their freshman year and was a resident assistant in Brown during Cheung’s freshman year, so he’s no stranger to either of them.

Parekh had seen both Cheung and Lee perform individually, but seeing them together in the audience at Lunar New Year?

“It’s a game-changer,” he said, laughing. “It’s a huge step mentally for them, and for other students who might like yoyoing.”

Despite being two experienced yoyoers, Lee and Cheung didn’t meet until the beginning of this semester. Lee, encouraged by his friends to try out for ASA’s Lunar New Year showcase, ran into Cheung at the audition. Unable to decide which yoyoer they wanted, ASA made the smart choice: both. It paid off.

Parekh was in the crowd that night at LNY, watching his friends perform.

“Cheung never smiles when he does stuff,” Parekh explained. “He’s just yoyoing. But up there, he was smiling and laughing with Lee.”

For him, the performance was more than just a show. It was a powerful statement from two incredibly talented but normally shy students.

“I’ve seen them both yoyoing, but the fact that they did it together and other people were cheering them?” Parekh laughed. “It just shows that not only is it fun to do, it’s fun to do together.”