Have you ever thought about what it takes to get a synthetic uterus through the TSA screening line at the airport? Neither had we—until we handed our documentation to the agents at RDU, scrambling to explain ‘Why, Sir,’ we were carrying bundles of pink gel and latex tubing in our backpacks.

Before arriving at Duke, we envisioned our first-year would consist of daily trips to Marketplace, intense conversations with friends late into the night, and jam-packed basketball games in Cameron. Like many Duke students, we were right to assume that these events would become staples of our first two semesters. However, we had not yet realized that, sometimes, the most memorable experiences emerge at unexpected times, in unexpected places, with unexpected people.

While other students were eased into their college coursework, we were catapulted into the engineering process in Pratt’s new first-year design course. Placed together on a team based on mutual interests, we were assigned a client and were tasked with designing and developing an accurate model of the female abdomen postpartum for use in medical device testing. Following the successful completion of the course, we made the decision to continue working on our project, this time pivoting to achieve a new set of goals.

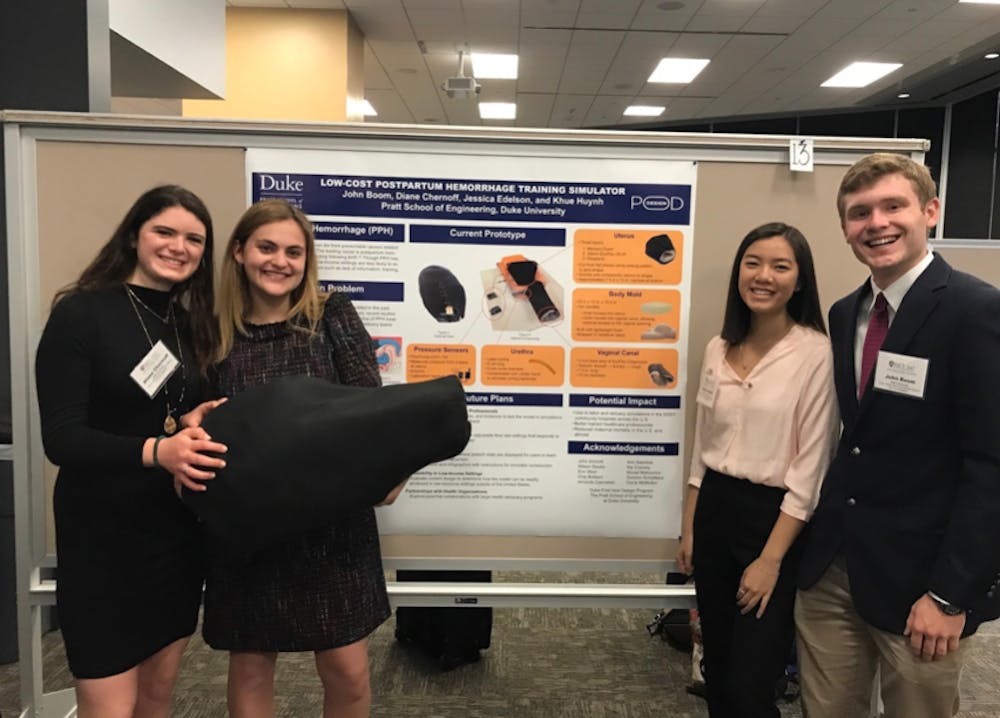

Over the past few months, we designed, prototyped, and presented a low-cost postpartum hemorrhage training simulator for use in rural and low-income U.S. hospitals. The simulator allows labor and delivery teams to practice the proper procedures to treat postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) at a very low cost: less than 100 dollars. Given that PPH is the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide, our work was driven by a desire to improve the delivery of healthcare here in the United States and to secure better maternal outcomes.

Though we learned a wide range of tangible skills and can now spit off every statistic relevant to maternal mortality, we believe that the most important lessons, as shared below, were learned beyond the bounds of a rubric.

Lesson 1: Effective teams are supportive teams

With multiple components being completed simultaneously, communication was critical to the development of our project. Our sense of team loyalty became our strongest asset. From helping each other through crazy workloads to practicing presentations in the middle of airports, we viewed each other not as competition, but as collaborators, and ultimately, friends.

Lesson 2: Think outside the box

Though engineering is often perceived on campus as rigid, we refused to subscribe to this notion. When faced with challenges, we drew upon other life experiences to assemble an eclectic array of materials. When we couldn’t find neoprene fabric at the local store, we ordered dozens of kiddie lunch boxes from Amazon. And, best of all, when we needed to find a cheap, water-based gel to model intestines, two gallons of lubricant saved the day. Yes, you read that right: lube. Just imagine when we submitted that item for reimbursement...

In doing all of this, we learned that design thinking doesn’t have to be formal and purely academic; all it takes is a good sense of humor and a spark (or two) of creativity.

Lesson 3: Learning from mistakes

Coming into the project, we were clearly not experts on what postpartum organs felt like. We fervently began researching and designing, creating over fifty uterus and many body prototypes before coming to our final iteration. We tried everything: rigid, sticky, solid, hollow, big, small. At one point, we sent a 3D life-sized uterus model to the printer. When we received the email notification that our print was ready, two minutes later, we retrieved a miniature uterus from the tray. Our scaling had been wrong, and we immediately burst out laughing. Another time, we wheeled our model on a cart through Duke Hospital to present it to a gynecologist. As the physician gave us feedback, the model’s ballistics gels began to melt. First, slowly, and then all at once.

The setbacks we encountered in both of these instances were frustrating, yet we learned to accept our mistakes and to use them to better determine how we could improve our design. After further tinkering with the 3D printers and evaluating new molding materials that wouldn’t melt at room temperature, we emerged with a more viable product to present to our clients. And then the iterative process, where failures inform design, began again.

Lesson 4: Unapologetic Ova-Achievements

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Upon finishing a prototype, one of our teammates shouted across a lecture hall, “Guys! I finished the uterus!” Immediately, all heads turned. Though vaginas and uteri had grown to be everyday staples of our vocabulary, many of our fellow classmates were surprised, and sometimes uncomfortable, listening to us talk about our project. Working in the women’s health space showed us how deeply entrenched stigmas related to female anatomy and reproduction are in our society, and we quickly grew to realize that we played a role in uprooting certain taboos. Half of the fun was standing alongside our unconventional project in order to raise awareness about maternal mortality.

Years from now, when we look back on our first-year, alongside all of the traditional Duke fun, we will remember our daily trips to the POD, the intense conversations with our team, and the jam-packed race to finish our project. In the most unexpected of ways, engineering taught us never to underestimate our abilities. The status quo is ova-rated, anyways.

Jess Edelson and Khue Huynh are first-year students who would like to thank TSA for letting them through #blessed.