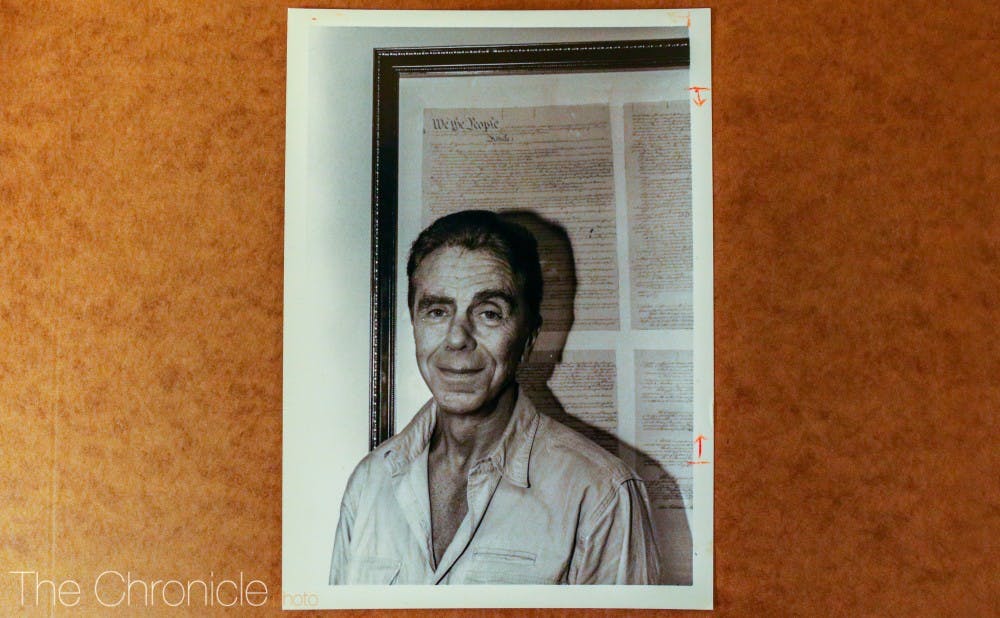

Even in his final days, a renowned Duke Law School First Amendment scholar made sure his legal voice was heard.

The News & Observer was appealing a libel case to the North Carolina Supreme Court, and William Van Alstyne was going to try his best to convince the Court to hear the case. Van Alstyne was a professor at Duke for nearly four decades until his 2004 retirement, and he was well-known for being “generous with his ideas” as well as his legal prowess.

The William R. and Thomas L. Perkins professor emeritus of law filed an amicus brief Jan. 11 before his death Jan. 29.

'The quintessential Duke Law experience'

The Journal of Legal Studies named him one of the 40 most frequently cited American legal scholars. Judges, lawyers and academics twice selected him in polls as one of the most qualified Supreme Court justice candidates in the country.

Van Alstyne may be best known for his First Amendment and free speech scholarship, but he was also an expert in other amendments, the Constitution, separation of powers, impeachments and civil rights. He famously argued in favor of individuals’ Second Amendment right to bear arms in 1994 for the Duke Law Journal and wrote a casebook on the "First Amendment in the Twenty-First Century."

Van Alstyne—known as “VA” to friends and colleagues—taught at the Law School from 1965 to 2004, during which he appeared numerous times before House and Senate committees, wrote countless legal articles and served as a "incredibly engaging, terrific teacher,” according to lawyer Mark Prak, Trinity ‘77 and J.D. ‘80, one of the professor's former students and a representative for the News & Observer in the libel case.

After graduating from the University of Southern California and Stanford Law School, Van Alstyne worked as California’s deputy attorney general and for the Justice Department on voting rights cases in the South. He became a professor at Ohio State University before joining Duke’s law school in 1965. He left in 2004 to go teach at William and Mary Law School until 2012, when he retired to sunny Southern California.

Despite his immense stature in the law community, he wasn’t a stuffy academic—he loved motorcycles and wore leather jackets to class.

“Bill was an intellectual giant,” Katharine Bartlett, A. Kenneth Pye professor of law and former dean of the Law School, said in the school's news release on his death. “No one did more to elevate the reputation of this law school into one of the premier law schools of this country, and no one was more generous with his ideas or in transmitting to students respect for the rule of law.”

Van Alstyne was highly regarded among his peers and students. Prak, who took his First Amendment seminar, called him the “quintessential Duke Law experience.”

Paul Carrington, the Harry R. Chadwick Sr. professor emeritus of law and dean of the Law School from 1978-88, succinctly described Van Alstyne in an email to The Chronicle.

“VA and I were old friends, having been colleagues at Ohio State,” Chadwick wrote. “He was an awesome teacher and scholar.”

The brief

The News & Observer was sued in 2011 by Beth Desmond, an N.C. State Bureau of Investigation agent who claimed that the paper libeled her in an investigative series about the SBI and caused her to experience post-traumatic stress disorder.

A Wake County jury awarded Desmond $9 million, and the N.C. Court of Appeals unanimously ruled in favor of Desmond while reducing the damages to $6 million in accordance with state law. The N&O is appealing to the N.C. Supreme Court in part because they allege the Superior Court judge gave improper instructions to the jury and would not admit evidence from a national review board that showed Desmond’s bullet fragmentation analysis didn’t support her expert testimony in murder cases.

In the brief that Van Alstyne filed asking the N.C. Supreme Court to consider the case, he argued that truth is an absolute defense for libel suits, regardless of whether the truth is discovered post-publication.

"In New York Times [v. Sullivan], the Court emphasized that the 'central meaning of the First Amendment' lay in the role it played in ensuring the conditions of self-government by protecting the public discussion of conduct of government officials," he wrote in the brief.

Even if the published material isn’t completely factual, he said, it isn’t defamation if revealing of the complete truth would have the same effect on the subject’s reputation.

“Any action that restricts the ‘breathing space’ the courts have repeatedly recognized as essential in this context must be viewed with constitutional skepticism, and a person sued by a public official for publishing statements critical of the official must be given wide latitude to prove the substantial truth of the publication,” Van Alstyne wrote in the brief.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Jake Satisky was the Editor-in-Chief for Volume 115 of The Chronicle.