The story of the Tower of Babel has an all-too familiar ending. Scattered across the face of the earth as a result of their trespass, unable to speak with one voice and in one language, humanity can no longer aspire to or endanger divine preeminence.

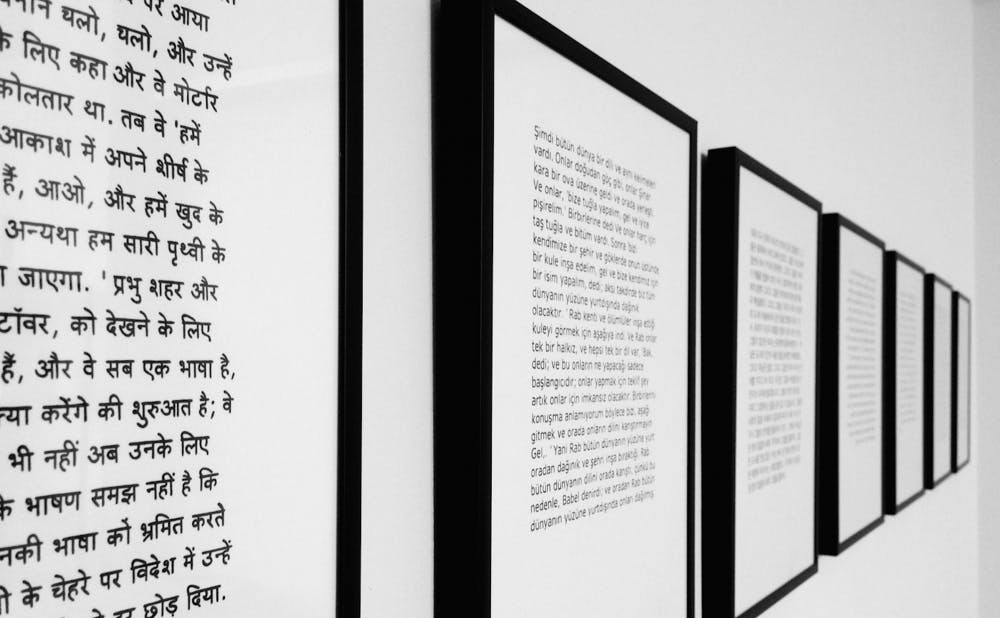

For Rebecca Kuzemchak, a conceptual artist based in New York City, this model of linguistic variation serves as inspiration for a re-examination of language as a point of convergence in a complex web of power. Her 2015 work “Babel," based on this biblical narrative, is currently on display at Louise Jones Brown Gallery in the Bryan Center.

When she was about to complete her MFA program almost five years ago, Kuzemchak was looking for ways to combine her interest in the overlap between religious, political and linguistic power with visual forms dealing with the removal of personal artistic labor in a manner that would make it accessible to a broad audience.

“I wanted it to be more political, something that folks beyond a traditional finite gallery theater might be better able to connect with,” she said.

When someone suggested she work on the Babel narrative and the so-called confusion of tongues as told in Genesis 11:1-9, Kuzemchak knew that she had not only found a text that would help her address her artistic concerns, but one with enough cultural currency to be recognizable even outside of a Judeo-Christian framework.

Using English as the base language, Kuzemchak ran the excerpt from Genesis through Google Translate multiple times, following the order in which the service acquired translation capability in a given language. When Kuzemchak started working on “Babel,” Google Translate still relied on an algorithm that broke down the text entered by users into single words or phrases. Drawing on a bilingual corpus of material readily accessible on the Internet, the service then calculated the probability of a given translation based on frequency of use. Effectively, this meant that the more information was available, the better the translation would be. Because the individual corpora differed significantly, both in size and in genre, accuracy varied accordingly. In cases where the corpus was of insufficient size, the service would fall back on English as an intermediary between languages.

Twenty one versions of verses translated in this way now ring the gallery, each offering a slightly different rendering of the text, each of them in some way faulty. At regular intervals, recordings she made of native speakers reading in their own language start playing, only adding to the proliferation of sounds in the gallery space.

For Kuzemchak, this way of relying on English as a default mode, a kind of linguistic broker, resulting in translations that paid little heed to grammar and none to the intricacies of idiomatic expression, provides evidence of a linguistic Anglocentrism that more generally bears on issues of socio-cultural control. “Babel” illustrates the power structures for which language is both the trigger and the facilitator.

Crucially, the original language Kuzemchak chooses to work with is not Hebrew, and is therefore itself only an imperfect derivation. The artist exacerbates this question of originality and authorship by combining technological means of production with manual labor. By handing over the task of translation to an algorithm and then merely reproducing its results by painstakingly copying them onto paper, she relinquishes any claim to an original authorial position, effectively alienating herself from her own work. The accuracy or inaccuracy of the translations will only be apparent to native speakers of the languages represented and not to the artist herself. If the story of the tower narrates the descent of humanity into a cacophony of mutually unintelligible sounds, “Babel” does not reverse the process so much as intensify the effect of verbal confusion; no one can access the work’s full meaning.

Mona Tong, DUU VisArts committee member in charge of the exhibition, agrees with Kuzemchak’s assessment of her work.

“‘Babel’ brings up an interesting discussion about language diversity and the power and authority of language,” she said.

Given the sheer number of texts that become newly available on the Internet every year, it is no surprise that the translation service had been rapidly improving right up until the point when, in 2016, Google decided to replace the old system and employ an algorithm based on deep learning instead. Now, adaptive neural networks are trained to first extract and then present information from parallel corpora without recourse to an intermediary language. Nonetheless, Kuzemchak’s work, by making recording a moment in time, has lost none of its relevance. What she likes most about “Babel,” she explains, is the way it implicates viewers and invites them to ponder their own subject positions as well as their possible complicity in the power dynamics it stages.

“Even though you’re absent from the work that’s on the wall, you’re the governing force behind the piece," she said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.