The Allen Building Takeover of 1969 was transformative, paving the way for the creation of the the African and African American Studies Department, among other reforms. Just more than a month after the occupation, University President Douglas Knight resigned.

Fifty years after the Allen Building Takeover, here’s a look back at the day and its aftermath.

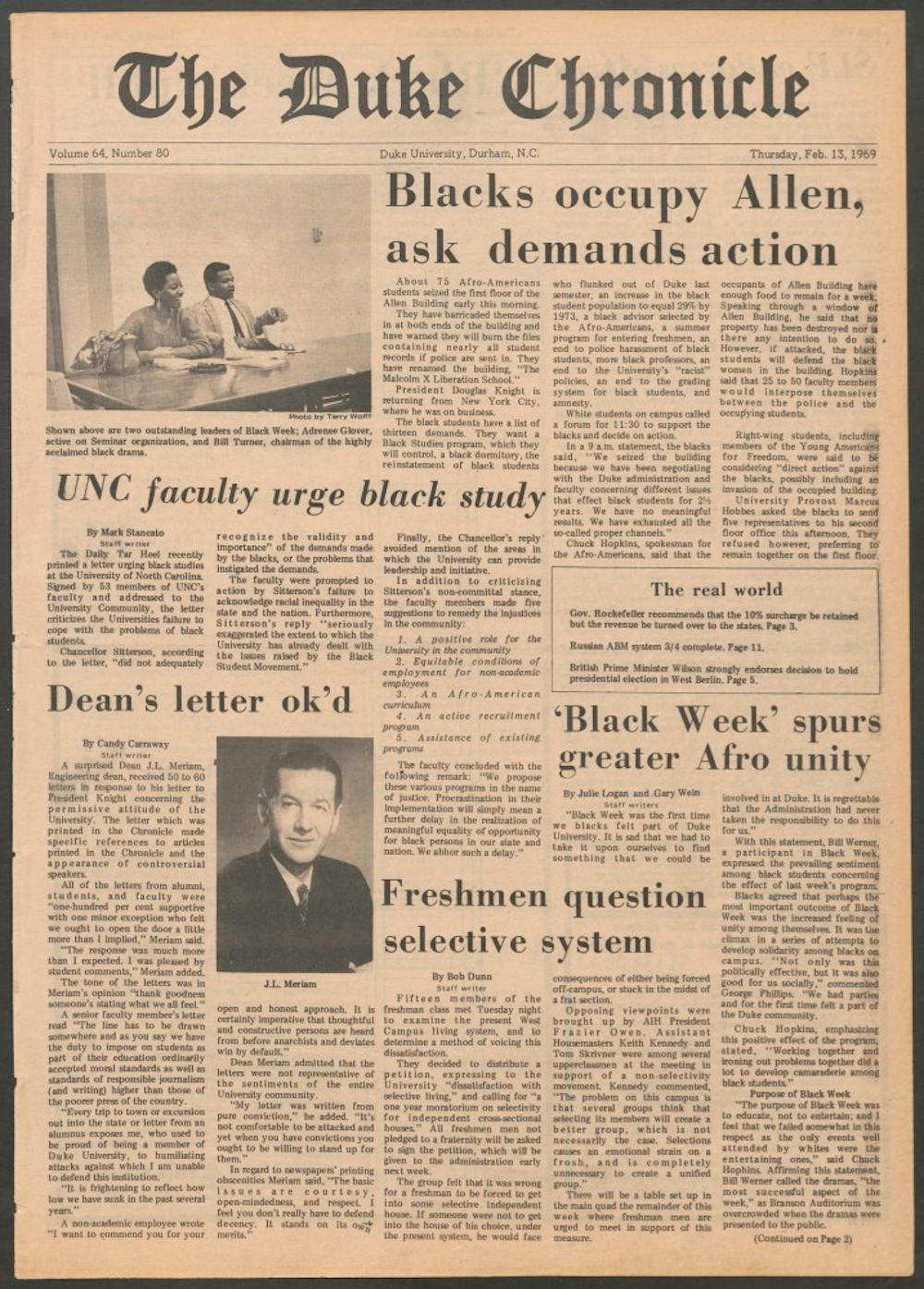

Morning of February 13, 1969: Students occupy the building

Dozens of students—most of whom were a part of the Afro-American Society—barricaded themselves in the first floor of the Allen Building on West Campus, Duke’s administrative headquarters, according to Duke University Libraries.

The students did so to highlight needs of African-American students, from a black student union to an African American studies department to protection from police harassment.

The students blocked the entrances to the building, warning that they would "burn the files containing nearly all student records if police [were] sent in." In a statement, the occupying students said that they had seized the building because they had “exhausted all the so-called proper channels” in negotiating with the administration.

Throughout the day: Some white students show support

Throughout the morning and early afternoon, students gathered in several places, according to an online exhibit by Duke University Libraries.

A public forum took place outside the Allen Building to discuss the takeover and white students held a “Sympathy School” on the Allen Building’s upper floors to "discuss how best to support the black students who were occupying the first floor."

At 2:30 p.m., a group of supportive white students gathered in the Chapel to discuss a plan of action. They decided to surround the Allen Building.

By the late afternoon, more than 400 white students surrounded the Allen Building to protect the protesters inside, according to the exhibit. The Chronicle reported the next day that the crowd had grown to around 1,500 people by the time police arrived.

3:30 to 5:15 p.m.: Duke issues ultimatums and the students leave the building

After hours of meetings between the protestors and school administration, provost Marcus Hobbs issued an ultimatum at 3:30 pm, ordering the students to leave the building within an hour.

Durham police arrived on campus to clear the building at 5:30 pm, but the protestors peacefully left at 5:15 p.m. According to the exhibit, an “outside adviser” had warned the students that the police were coming.

5:30 p.m.: Students clash with police

The students may have left the building without a fight, but things soon turned violent on West Campus. As the predominantly white protesters walked down Campus Drive, the students who had gathered nearby marched on the quad, some chanting “it ain’t over yet!”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Sign up for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

After one protester allegedly threw a rock at a police officer, the police responded by firing tear gas. The students fled, but several more confrontations followed after the police retreated back toward the building.

At the end of the roughly 90-minute struggle, 23 students and two police officers were injured and the crowd forced the police back into the building. The officers eventually left through the back.

February 15: President Knight speaks to the university

On February 15, university president Douglas Knight delivered a speech that was broadcast on WDBS, Duke’s campus radio station at the time. He said that illegally occupying buildings “is no way in which to resolve a problem. It only compounds it.”

However, he expressed his “long standing and deep concern” for black students and promised that two committees within the administration would work to improve their status.

Knight lamented that it was necessary to bring police onto the campus and asked for the “mature judgement and…sympathetic forbearance” of the Duke community in working through what he described as a “very difficult experience.”

February 19: Student leaders resign in solidarity

On February 19, the student members of Duke’s Student-Faculty Advisory Committee (SFAC) “temporarily resigned their membership” in protest of the administration’s resistance to change.

Wade Norris, a member of the committee and the president of Duke’s student government, said that the move would make it clear to the student body that students, including the SFAC, had no input into the “large and basic issues of university policy.” He recalled having gone to Knight the previous fall with concerns that racial tensions could develop into a crisis, and said that Knight would not commit to any reforms.

March 4 to 13: Faculty committee recommends the creation of an African Studies program

In early March, concrete changes to university policy began to emerge from the crisis. On March 4, a faculty committee recommended the establishment of “a program in African and Afro-American studies” at Duke.

One member of the committee, James Graham, urged the creation of a Department of Afro-American studies. However, the majority report called only for an interdepartmental major.

On March 13, the Undergraduate Faculty Council approved a resolution by which a Supervisory Committee for the new program would consist of five faculty members and three black students.

March 10 to 17: Black students announce they will withdraw in protest

On March 10, 23 black students announced that they would withdraw from the university. Seventeen more announced plans to withdraw at the end of the semester. Chuck Hopkins, a second-semester senior at the time, said that the move was in protest of “the inhuman conditions we have been subjected to.”

Days later, several of the students announced plans to found the Malcolm X Liberation University, which would focus on courses in African-American history. The school operated until 1973.

On March 17, the Duke Afro-American Society announced that the students who had withdrawn would remain at Duke after all in order to “continue the struggle” for racial justice.

March 19: Protesters placed on probation

In early March, the university’s legal advisor recommended disciplinary charges against twenty-five students involved in the protest. The students were charged with violating the Pickets and Protest Policy.

A five-man Hearing Committee chaired by law professor A. Kenneth Pye heard the trial on March 19. The students did not contest the charges, and the hearing focused on the punishment they would receive. The committee ultimately placed 47 students on probation for one year.

March 31: President Knight resigns

On March 31, 1969, Douglas Knight resigned as the president of Duke University. He said in a statement that he had “an obligation to protect my family from the severe and sometimes savage demands” of running a university.

Knight’s resignation was effective June 30.

December 13: Sanford named president

On December 13, the Board of Trustees elected Terry Sanford as Duke’s new president. Sanford had served as the governor of North Carolina from 1961 to 1965.

During his 15-year tenure at Duke, Sanford worked closely with protestors to prevent a repeat of the events that undid his predecessor. The Sanford School of Public Policy now bears his name.

After leaving Duke in 1985, he served a term in the United States Senate from 1987 to 1993.

Matthew Griffin was editor-in-chief of The Chronicle's 116th volume.